“Stephen, I’m scared.”

“Sylvia, it’s all going to be all right.”

Up past Union Square, Madison Square and all the hotels, where in each I wonder who it is who lonely lurks. The Flatiron Building like the prow of a ship sailing north on Broadway. Turn west on Thirty-first Street. St. Francis of Assisi Monastery right in the middle of the block. And arriving safely. The Travelers Aid Society, whose office is in this massive station housing the Pennsylvania, the Long Island, Lehigh Valley, the New York, New Haven, and Hartford railroad lines.

With her cloak aflow and a slender bouquet of red roses and a white-beribboned aqua box from Tiffany’s tucked in her arm, Sylvia bought and paid for parlor-car tickets. The train moving slowly off through the darkness of the tunnel under the Hudson. Stare out into the passing bulbs of light and the snaking wires, pipes, and conduits. Sylvia pulling off her black kidskin gloves. Leafing through her pile of magazines and newspapers. Quickly reading as she turned the pages with her manicured fingernails. A faint trace of lipstick on her lips and a white silk scarf held at her throat with the long gold pin that she wore in her stock while foxhunting. Any second I thought she might turn to me and say, You’re fucking my adoptive mother. Or, That son of a bitch Max friend of yours, who married my best friend for her money and ruined her life. But she leafed again and again through the fashion magazines and even fell asleep for a while between the towns of Poughkeepsie and Albany.

Outside the station at Syracuse, I got increasingly nervous as I somehow sensed that Sylvia’s mother did not have a long driveway up to her mansion and a Gilbert administering her household. And Sylvia’s hand trembled showing the taxi driver an address on a piece of paper, as if she didn’t want to say it out loud. And I could see why by the questionable first reaction of the taxi driver and his further suspiciousness as we progressed through Main Street to what was clearly the wrong side and shabby part of town. Stopping on a potholed unpaved road of warehouses, shacks and an engineering works parallel to the railway tracks. Sylvia anxiously leaning forward in her seat, glancing at the slip of paper in her hand.

“Driver, this couldn’t be the place.”

“Ma’am, this is the road you showed me on the paper. And there’s the number forty-eight right there plain as can be seen.”

“Jesus Christ. Well then, wait.”

“You betcha, ma’am. It sure looks like rain.”

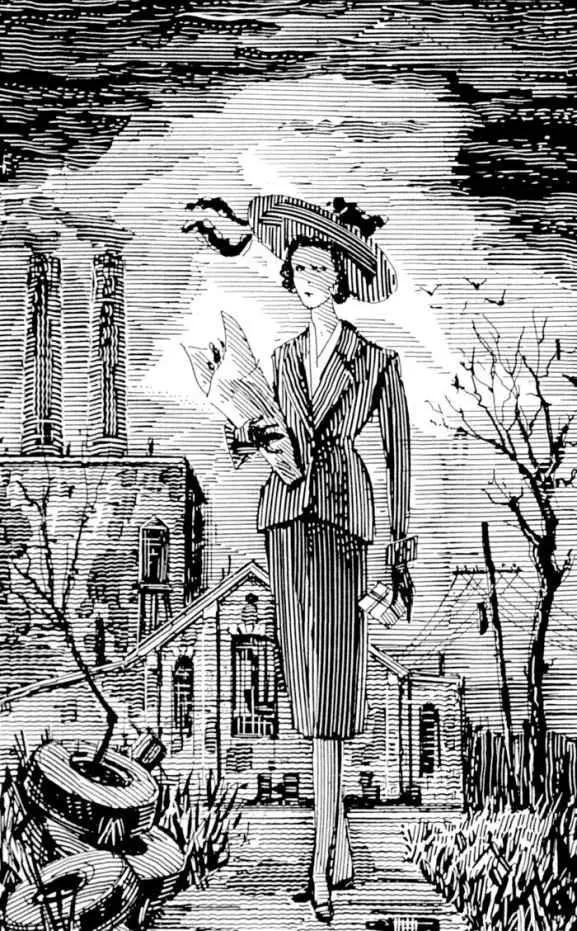

Sylvia leaving her cloak behind her, climbing out of the taxi and standing on the roadway in front of the closed garage doors of a car-repair shop. And hesitating at the foot of a flight of ramshackle stairs up the side of a dirty paint-peeling brown clapboard frame building backing onto the railroad tracks. Shades drawn on two windows on the floor above the garage door. A sign. DRINK MISSION BELL SODA. Behind the building, a great monster of puffing steam passing, pulling a freight train. The taxi driver turning to speak over his shoulder.

“That old freight could take its own good time going by on its good way to Chicago via Buffalo and Cleveland.”

The grinding squealing wheels as a pair of hoboes lope alongside the open doors of a big boxcar, hopping on board. One missing and stumbling, the other grabbing him up by the coat and hand. At least loyalty somewhere, friend to friend. Sylvia still waiting on the roadway, her bag on a strap over her shoulder, her white-beribboned aqua box from Tiffany’s couched in the crook of her arm. The wail of the train’s whistle in D Major. Then the elegance of this black figure suddenly climbing up the worn and broken wooden stairs to a landing at the top, and pausing at a rusting screen door. Move to where I can see in case some unknown hostile hand drags Sylvia in. Get out of the car and step up on the broken sidewalk. A passing vagrant stopping. Seems to be one wherever I go, always asking for the same dime. And got to give him something. Who knows, he might have been in the war.

“Hey, mister, got a dime. For a cup of coffee. Or maybe you could spare a quarter for something to eat.”

Reach into my pocket and flip what will soon be my last quarter toward this wanderer who, missing the catch, picks the coin up out of a small puddle of water. Wipes it on his sleeve, puts it in his pocket. But for the solemn sadness in the man’s face, you could envy him his freedom, with no one taking the trouble to denigrate him. Someone’s father, brother, could even have been in a gun turret on the old Missouri.

Sylvia standing still as a statue. The last cars of the train passing. The caboose with it’s rear red lights disappearing with another faraway lonesome wail of the train’s whistle. Sylvia maneuvering her Tiffany box and bouquet of red roses to peel off one of her black kidskin gloves. Pulling open the outside rusted screen door and pressing a bell. A dog barking. The faint tune of chimes ringing. The first bars of “Home on the Range.” The shadow of a figure inside the screen door as it opens, slightly ajar. Sylvia stepping back. A woman, wisps of dyed blond hair in curlers, one hand holding closed her pink dressing gown at her throat. A growling, gruff woman’s voice.

“What do you want.”

“Annie, I’m Sylvia, your daughter. And I know you are my mother.”

The sound of the waiting silence. This slattern and slovenly coarse woman in her soiled pink dressing gown suddenly lunging out the half-open rusting screen door and spitting into Sylvia’s face.

“I know who you are. Get the hell out of here, you bitch, all dressed up to the nines, and leave me alone and don’t come back.”

First drops of rain beginning to fall out of blackening skies. A tight constriction in the throat. A shudder in the breast. How could the sorrow ever be greater that you can feel for someone so distressed in a grief so deep. To offer to take their hand and lead them away from hurt. As once was offered me as a little boy when big tears welled and rolled out of my eyes and down my cheeks when someone said I was bad.

Sylvia descending the wooden steps, a purple silk handkerchief wiping the sprinkle of moisture from her face. Her bag slung askew across a shoulder, tears bulging in her reddening eyes. Her gloved hand holding the glove from the other hand and her shiny aqua box from Tiffany’s and the bouquet of red roses under her arm. On the last step, her ankle twisting as she slips. A wounded animal cry. As she turns. Raises an arm. Throwing away the red roses on top of a pile of old tires stacked underneath the stairs. And dropping the Tiffany box to the ground, kicking it away with the toe of her black patent-leather shoe to join the grimy debris of the gutter.

“My mother. Jesus, that was my mother.”

The next train back down to New York was in another hour. Sylvia, in a defiant gesture of extravagance on top of the modest fare tipped the taxi driver ten dollars.

“I sure thank you kindly, ma’am. Hope to see you again sometime.”

“You won’t. But thanks.”

In the station Sylvia sat on a bench as I walked back and forth on the platform. A guy trying to pick her up soon retreated away from her absolute silence. As she stared up at him, through him. And away from him. On the train, as I sat on the aisle Sylvia looked out the window. I tried to comfort her with a gentle pat on the arm.

“You, you’ve had a family. You know what it’s like to have a father and mother. You knew real sisters and brothers. Well I found my real mother through the Red Cross tracing service. And exactly as I used to think she was. In a shack by the railway tracks. And I won’t ever know now what her face is like when it’s smiling. Or when it’s sad. But I sure as hell know what it’s like when it’s mad.”

Читать дальше