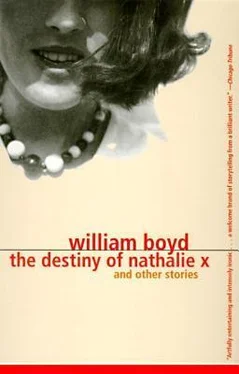

William Boyd - The Destiny of Nathalie X

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Boyd - The Destiny of Nathalie X» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Destiny of Nathalie X

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Destiny of Nathalie X: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Destiny of Nathalie X»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Destiny of Nathalie X — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Destiny of Nathalie X», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I am humbled further when I consider the family’s disarming, disinterested kindness. When I arrived in Nice they were the only contacts I had in the city, and at my mother’s urging, I duly wrote to them citing our tenuous connection via my mother’s friends. To my surprise I was promptly invited to dinner and then invited back every Monday night. What shamed me was that I knew I myself could never be so hospitable so quickly, not even to a close friend, and what was more, I knew no one else who would be, either. So I cross the Cambrai threshold each Monday with a rich cocktail of emotions gurgling inside me: shame, guilt, gratitude, admiration and — it goes without saying — lust.

Preston’s new address is on the Promenade des Anglais itself — the “Résidence Les Anges.” I stand outside the building, looking up, impressed. I have passed it many times before, a distressing and vulgar edifice on this celebrated boulevard, an unadorned rectangle of coppery, smoked glass with stacked ranks of gilded aluminum balconies.

I press a buzzer in a slim, freestanding concrete post and speak into a crackling wire grille. When I mention the name “Mr. Fairchild,” glass doors part softly and I am admitted to a bare granite lobby where a taciturn man in a tight suit shows me to the lift.

Preston rents a small studio apartment with a bathroom and kitchenette. It is a neat, pastel-colored and efficient module. On the wall are a series of prints of exotic birds: a toucan, a bateleur eagle, something called a blue shrike. As I stand there looking around I think of my own temporary home, my thin room in Madame d’Amico’s ancient, dim apartment, and the inefficient and bathless bathroom I have to share with her other lodgers, and a sudden hot envy rinses through me. I half hear Preston enumerating various financial consequences of his tenancy: how much this studio costs a month; the outrageous supplement he had to pay even to rent it in the first place; and how he had been obliged to cash in his return fare to the States (first-class) in order to meet it. He says he has called his father for more money.

We ride up to the roof, six stories above the Promenade. To my vague alarm there is a small swimming pool up here and a large glassed-in cabana — furnished with a bamboo bar and some rattan seats — labeled Club Les Anges in neon copperplate. A barman in a short cerise jacket runs this place, a portly, pale-faced fellow with a poor mustache whose name is Serge. Although Preston jokes patronizingly with him it is immediately quite clear to me both that Serge loathes Preston and that Preston is completely unaware of this powerful animus directed against him.

I order a large gin and tonic from Serge and for a shrill palpitating minute I loathe Preston too. I know there are many better examples on offer, of course, but for the time being this shiny building and its accoutrements will do nicely as an approximation of The Good Life for me. And as I sip my sour drink a sour sense of the world’s huge unfairness crowds ruthlessly in. Why should this guileless, big American, barely older than me, with his two thousand cigarettes and his cashable first-class air tickets have all this … while I live in a narrow frowsty room in an old woman’s decrepit apartment? My straitened circumstances are caused by a seemingly interminable postal strike in Britain which means money cannot be transferred to my Nice account and I have to husband my financial resources like a neurotic peasant conscious of a hard winter lowering ahead. Where is my money, I want to know, my exotic bird prints, my club, my pool? How long will I have to wait before these artifacts become the commonplace of my life?… I allow this unpleasant voice to whine and whinge on in my head as we stand on the terrace and admire the view of the bay. One habit I have already learned, even at my age, is not to resist these fervent grudges — give them a loose rein, let them run themselves out, it is always better in the long run.

In fact I am drawn to Preston and want him to be my friend. He is tall and powerfully built — the word “rangy” comes to mind — affable and not particularly intelligent. To my eyes his clothes are so parodically American as to be beyond caricature: pale blue baggy shirts with button-down collars, old khaki trousers short enough to reveal his white-socked ankles and big brown loafers. He has fair, short hair and even, unexceptionable features. He has a gold watch, a Zippo lighter and an ugly ring with a red stone set in it. He told me once, in all candor, in all modesty, that he “played tennis to Davis Cup standard.”

I always wondered what he was doing in Nice, studying at the Centre. At first I thought he might be a draftee avoiding the war in Vietnam but I now suspect — based on some hints he has dropped — that he has been sent off to France as an obscure punishment of some sort. His family doesn’t want him at home: he has done something wrong and these months in Nice are his penance.

But hardly an onerous one, that’s for sure: he has no interest in his classes — those he can be bothered to take — or in the language and culture of France. He simply has to endure this exile and he will be allowed to go back home, where, I imagine, he will resume his soft life of casual privilege and unreflecting ease once more. He talks a good deal about his eventual return to the States, where he plans to impose his own particular punishment, or extract his own special reward. He says he will force his father to buy him an Aston Martin. His father will have no say in the matter, he remarks with untypical vehemence and determination. He will have his Aston Martin, and it is the bright promise of this glossy English car that really seems to sustain him through these dog days on the Mediterranean littoral.

Soon I find I am a regular visitor at the Résidence Les Anges, where I go most afternoons after my classes are over. Preston and I sit in the club, or by the pool if it is sunny, and drink. We consume substantial amounts (it all goes on his tab) and consequently I am usually fairly drunk by sunset. Our conversation ranges far and wide, but at some point in every discussion Preston reiterates his desire to meet French girls. If I do indeed know some French girls, he says, why don’t I ask them to the club? I reply that I am working on it, and coolly change the subject.

Over the days, steadily I learn more about my American friend. He is an only child. His father (who has not responded to his requests for money) is a millionaire — real estate. His mother divorced him recently to marry another, richer millionaire. Between his two sets of millionaire parents Preston has a choice of eight homes to visit in and around the USA: in Miami, New York, Palm Springs and a ranch in Montana. Preston dropped out of college after two semesters and does not work.

“Why should I?” he argues reasonably. “They’ve got more than enough money for me too. Why should I bust my ass working trying to earn more?”

“But isn’t it … What do you do all day?”

“All kinds of shit … But mostly I like to play tennis a lot. And I like to fuck, of course.”

“So why did you come to Nice?”

He grins. “I was a bad boy.” He slaps his wrist and laughs. “Naughty, naughty Preston.”

He won’t tell me what he did.

It is Spring in Nice. Each day we start to enjoy a little more sunshine, and whenever it appears, within ten minutes there is a particular girl, lying on the plage publique in front of the Centre, sunbathing. Often I stand and watch her spread out there, still, supine, on the cool pebbles — the only sunbather along the entire bay. It turns out she is well known, that this is a phenomenon that occurs every year. By early summer her tan is solidly established and she is very brown indeed. By August she is virtually black, with that kind of dense, matte tan, the life burned out of the skin, her pores brimming with melanin. Her ambition each year, they say, is to be the brownest girl on the Côte d’Azur …

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Destiny of Nathalie X»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Destiny of Nathalie X» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Destiny of Nathalie X» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.