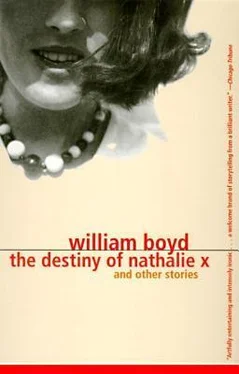

William Boyd - The Destiny of Nathalie X

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Boyd - The Destiny of Nathalie X» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Destiny of Nathalie X

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Destiny of Nathalie X: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Destiny of Nathalie X»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Destiny of Nathalie X — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Destiny of Nathalie X», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Gerald offered him one of his small cigars.

Dr. Liceu Lobo put down his coffee cup and relit his real excelente . He drew, with pedantic and practiced care, a steady thin stream of smoke from the neatly docked and already nicely moist end and held it in his mouth, savoring the tobacco’s dry tang before pluming it at the small sunbird that pecked at the crumbs of his pastry on the patio table. The bird flew off with a shrill shgrreakakak and Dr. Liceu Lobo chuckled. It was time to return to the clinic, Senhora Fontenova was due for her vitamin D injections.

He felt Adalgisa’s hand on his shoulder and he leaned his head back against her firm midriff, her finger trickled down over his collarbone and tangled and twirled the dense gray hairs on his chest.

“Your mother wants to see you.”

Wesley swung open the gate to his small and scruffy garden and reminded himself yet again to do something about the clematis that overburdened the trellis on either side of his front door. Pauline was bloody meant to be i.c. garden, he told himself, irritated at her, but then he also remembered he had contrived to keep her away from the house the last month or so, prepared to spend weekends and the odd night at her small flat rather than have her in his home. As he hooked his door keys out of his tight pocket with one hand he tugged with the other at a frond of clematis that dangled annoyingly close to his face, and a fine confetti of dust and dead leaves fell quickly onto his hair and shoulders.

After he had showered he lay naked on his bed, his hand on his cock, and thought about masturbating but decided against. He felt clean and, for the first time that day, almost relaxed. He thought about Margarita and wondered what she looked like with her clothes off. She was thin, perhaps a little on the thin side for his taste, if he were honest, but she did have a distinct bust and her long straight hair was always clean, though he wished she wouldn’t tuck it behind her ears and drag it taut into a lank swishing ponytail. Restaurant regulations, he supposed. He realized then that he had never seen her with her hair down and felt, for a moment, a sharp intense sorrow for himself and his lot in life. He sat up and swung his legs off the bed, amazed that there was a shimmer of tears in his eyes.

“God. Jesus!” he said mockingly to himself, out loud. “Poor little chap.”

He dressed himself brusquely.

Downstairs, he poured himself a large rum and coke and put Milton Nascimento on the CD player and hummed along to the great man’s ethereal falsetto. Never failed to cheer him up. Never failed. He took a great gulp of the chilled drink and felt the alcohol surge. He swayed over to the drinks cabinet and added another slug. It was only four-thirty in the afternoon. Fuck it, he thought. Fuck it.

He should have parked somewhere else, he realized crossly, as unexpected sun warmed the Rover while he waited outside Pauline’s bank. He didn’t have a headache but his palate was dry and stretched and his sinuses were responding unhappily to the rum. He flared his nostrils and exhaled into his cupped hand. His breath felt unnaturally hot on his palm. He sneezed, three times, violently. Come on, Pauline. Jesus.

She emerged from the stout teak doors of the bank, waved and skittered over toward the car. High heels, he saw. She has got nice legs. Definitely, he thought. Thin ankles. They must be three-inch heels, he reckoned, she’ll be taller than me. Was it his imagination or was that the sun flashing off the small diamond cluster of her engagement ring?

He leaned across the seat and flung the door open for her.

“Wesley! You going to a funeral or something? Gaw!”

“It’s just a suit. Jesus.”

“It’s a black suit. Black. Really.”

“Charcoal gray.”

“Where’s your Prince of Wales check? I love that one.”

“Cleaners.”

“You don’t wear a black suit to a christening, Wesley. Honestly.”

Professor Liceu Lobo kissed the top of his mother’s head and sat down at her feet.

“Hey, little Mama, how are you today?”

“Oh, I’m fine. A little closer to God.”

“Nah, little Mama, He needs you here, to look after me.”

She laughed softly and smoothed the hair back from his forehead in gentle combing motions.

“Are you going to the university today?”

“Tomorrow. Today is for you, little Mama.”

He felt her small rough hands on his skin at the hairline and closed his eyes. His mother had been doing this to him ever since he could remember. Soothing, like waves on the shore. “Like waves on the shore your hands on my hair”… The line came to him and with it, elusively, a hint of something more. Don’t force it, he told himself, it will come. The rhythm was fixed already. Like waves on the shore. The mother figure, mother earth … Maybe there was an idea to investigate. He would work on it in the study, after dinner. Perhaps a poem? Or maybe the title of a novel? As ondas em la praia . It had a serene yet epic ring to it.

He heard a sound and looked up, opening his eyes to see Marialva carrying a tray. The muffled belling of ice in a glass jug filled with a clear fruit punch. Seven glasses. The children must be back from school.

Wesley looked across the room at Pauline trying vainly to calm the puce, wailing baby. Daniel-Ian Young, his nephew. It was a better name than Wesley Bright, he thought — just — though he had never come across the two Christian names thus conjoined before. Bit of a mouthful. He wondered if he dared point out to his brother-in-law the good decade-odd remorseless bullying that lay ahead for the youngster once his peers discovered what his initials spelled. He decided to store it away in his grudge-bunker as potential retaliation. Sometimes Dermot really got on his wick.

He watched his brother-in-law, Dermot Young, approach, two pint-tankards in hand. Wesley accepted his gladly. He had a terrible thirst.

“Fine pair of lungs on him, any road,” Dermot said. “You were saying, Wesley.”

“—No, it’s a state called Minas Gerais, quite remote, but with this amazing musical tradition. I mean, you’ve got Beto Guedes, Toninho Horta, the one and only Milton Nascimento, of course, Lo Borges, Wagner Tiso. All these incredible talents who—”

“—HELEN! Can you put him down, or something? We can’t hear ourselves think, here.”

Wesley gulped fizzy beer. Pauline, relieved of Daniel-Ian, was coming over with a slice of christening cake on a plate, his mother in tow.

“All right, all right,” Pauline said, with an unpleasant leering tone to her voice, Wesley thought. “What are you two plotting? Mmm?”

“Where did you get that suit, Wesley?” his mother asked, guilelessly. “Is it one of your dad’s?”

There was merry laughter at this. Wesley kept a smile on his face.

“No,” Dermot said. “Wes was telling me about this bunch of musicians from—”

“—Brazil.” Pauline’s shoulders sagged and she turned wearily to Wesley’s mother. “Told you, didn’t I, Isobel? Brazil. Brazil. Told you. Honestly.”

“You and Brazil,” his mother admonished. “It’s not as if we’ve got any Brazilians in the family.”

“Not as if you’ve even been there,” Pauline said, a distinct hostility in her voice. “Never even set foot.”

Wesley silently hummed the melody from a João Gilberto samba to himself. Gilberto had taken the traditional form and distilled it through a good jazz filter. It was João who had stripped away the excess of percussion in Brazilian music and brought bossa nova to the—

“Yeah, what is it with you and Brazil, Wes?” Dermot asked, a thin line of beer suds on his top lip. “What gives?”

WHUCHINNNNNNG! WHACHANNNNGGG!! Liceu Lobo put down his guitar, and before selecting the mandolin he tied his dreadlocks back behind his head in a slack bun. Gibson Piaçava played a dull roll on the zabumba and Liceu Lobo began slowly to strum the musical phrase that seemed to be dominating “The Waves on the Shore” at this stage in its extemporized composition. Joel Carlos Brandt automatically started to echo the mandolin phrases on his guitar and Bola da Rocha plaintively picked up the melody on his saxophone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Destiny of Nathalie X»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Destiny of Nathalie X» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Destiny of Nathalie X» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.