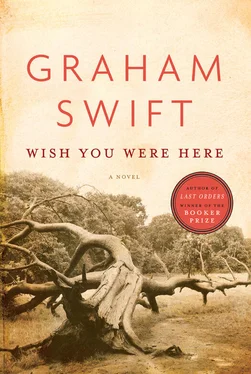

That oak, Jack might have added, was reckoned to be over five hundred years old. It had been there before the farmhouse.

Michael had put on the same clothes that he might have put on, a little later that morning, to do the tasks that had to be done about the farm: a check shirt, a thick grey jumper, corduroy trousers, long thick socks to go in Wellington boots — all of this in addition to the long-john underwear which in winter he normally slept in anyway. The suit he’d briefly worn only hours before (this was later noted) was back in the depths of the wardrobe. Then he’d put on his cap and scarf and his donkey jacket with the torn quilt lining, and the olive-green wool mittens that stopped short at the knuckles. So you might have said that he’d certainly felt the cold, given that he’d dressed so thoroughly for it. But all this was the force of habit. These clothes were like his winter hide, which he merely slipped off overnight. And, of course, he did have a task to complete. He even needed to make sure his fingers wouldn’t go numb and useless on him.

He took the gun from the cabinet and took two number-six cartridges and either loaded them straight away, with the kitchen light on to help him, or loaded them at the last minute, in the dark and the cold. At either point it would have been an action of some finality.

The question would arise, which Jack, since he was asleep himself, could never answer, as to how much, if at all, Michael had slept that night: how, in short, he’d arrived at his course of action and its particular timing. He could hardly have set his alarm clock. Jack discovered no note, though he didn’t tell the investigating policemen that he didn’t find this surprising, and when asked by them if he’d noticed anything strange in his father’s behaviour on the preceding day, he’d said only that they’d gone together to attend the short eleven-o’clock remembrance service beside the memorial in Marleston, as they did every year, because of the Luxtons who were on it. One of the two policemen, the local constable, Bob Ireton, would have been able to corroborate this directly, as he’d attended the ceremony himself, in his uniform, in a sort of semi-official capacity. It wasn’t, therefore, a typical Sunday morning — they didn’t put on suits every Sunday morning — but there was nothing strange about it, as PC Ireton would have wholly understood. It would have been strange if they hadn’t gone. The only things that were strange about it, Jack had affirmed, were that Tom wasn’t there (though the whole village knew why this was) and that they hadn’t gone for the usual drink in the Crown afterwards.

And Jack had left it at that.

There were two other peculiarities about that (already highly peculiar) night that he might have remarked on, setting aside the peculiarity of where the act occurred — which Jack, in his fashion, suggested wasn’t peculiar at all. One was that when he’d got up that night, suddenly galvanised into wakefulness and action, having somehow heard the shot and having somehow known what it meant, he’d naturally looked, even before hastily dressing and before (torch in hand) he left the farmhouse, into his father’s bedroom — into what had always been known as the Big Bedroom. And had noticed that the bedclothes, recently pulled back, had an extra blanket — a tartan one — spread over them. There was nothing special about an extra blanket on a cold night, so in that respect it was unworthy of mention. Only Jack knew that he’d never seen that blanket spread over his father’s bed before. Only Jack knew its history.

And Jack never mentioned either — was it relevant? — that there was a dog buried a little further down that field.

The second peculiarity — which Jack did point out, though the police might soon have discovered it for themselves — was that when Michael had dressed that night, he’d slipped a medal into the breast pocket of his frayed-at-the-collar check shirt. It was the same medal, of course, that Jack knew had been earlier that day in the pocket of his suit.

Why, later, the medal was in the pocket of his shirt was anyone’s guess, but it would have meant — though Jack didn’t go into this in his statement — that he must have been conscious of it during the intervening hours, and perhaps never returned it to its silk-lined box. He might have put it, for example, on his bedside table when he went to bed and before he slept, if he did sleep, that night. Perhaps — though this was a thought that would not crystallise in Jack’s mind till many years later — he might even have clutched it in his hand.

These were considerations that Jack felt the police and, later, the coroner need not be interested in. Any more than they need be interested in the fact that Vera had died (and hers wasn’t a quick death) in that same big bed with a tartan blanket now lying on it. Or that he himself had been born and, in all probability, conceived in it.

But the fact was that Michael had died wearing, so to speak, the DCM.

When the police had asked Jack how he’d discovered this so soon — after all, his father had been wearing two layers of thick clothing over his shirt, and anyway Jack was having to confront much else — Jack had said that he’d slipped his hand inside his father’s jacket to feel if his heart was still beating. The policemen had looked at Jack. They might have said, if they’d had no regard for his feelings, something like: ‘He’d just shot his brains out.’ Jack had nonetheless insisted, with a certain dazed defiance, that he’d wanted to feel his father’s heart, he’d wanted to put his hand over it. That had been his reaction. He didn’t say that he’d wanted to feel not so much a beating heart — which would have been highly unlikely — but just if there was any last living warmth left on that cold night, beneath the old grey jumper, in his father’s body.

But he said that he’d felt something hard there. Those were his actual words: he’d felt ‘something hard there’.

When Jack said these things the two policemen — Ireton and a Detective Sergeant Hunt — had looked away. Jack was clearly in a state of great distress and shock. God knows what state he would have been in when he actually came upon the body. Bob Ireton knew Jack Luxton to be a pretty impervious, slow-tempered sort. He was looking now, for Jack, not a little wild-eyed. Bob had been at the same primary and secondary schools as Jack. He’d known, from its beginning, about Jack and Ellie Merrick — but then so did the whole village. Save for Ellie and his recently absconded brother (and Tom, as Bob would later observe, was not to reappear for the funeral), Jack was pretty much alone now in the world.

Bob Ireton was basically anxious — he couldn’t speak for his plainclothes superior — to get this whole dreadful mess cleared up as quickly as possible and spare its solitary survivor any further needless torture. Poor man. Poor men. Both. Bob’s view of the matter — again, he couldn’t speak for his colleague — was as straightforward as it was considerate. Michael Luxton had killed himself with a shotgun. His son had discovered the fact and duly reported it to the authorities. In a little while from now, though there’d be a delay for an inquest, poor Jack would have to stand again in that suit he rarely wore, but had worn, as it happened, only the day before the death, beside his father’s grave.

This was not the first time, in fact, that Constable Ireton had been required to attend the scene after the suicide of a farmer. Following the cattle disease, there had been this gradual, much smaller yet even more dismaying epidemic. One or two hanged themselves from a beam in a barn (sometimes watched by munching cattle), others chose a shotgun. A shotgun was marginally more upsetting. Bob frankly didn’t attach much weight to the odd circumstantial details that sometimes went with a suicide, the strange things that might precede it, the strange things that might (it was not a good word) trigger it. It was a pretty extreme bit of behaviour anyway. Who could say what you (but that was not a good line of thinking and anyway not professional) might do?

Читать дальше

![Питер Джеймс - Wish You Were Dead [story]](/books/430350/piter-dzhejms-wish-you-were-dead-story-thumb.webp)