For Hilary, Mavis, Valerie,

Valda, Sue, Terri and Anji

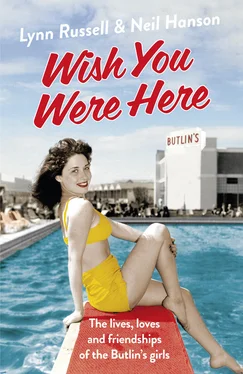

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Hilary

One

Two

Three

Mavis

One

Two

Three

Four

Valerie

One

Two

Three

Valda

One

Two

Three

Four

Sue

One

Two

Three

Terri

One

Two

Three

Four

Anji

One

Two

Three

Epilogue

Butlin’s Rules

Acknowledgements

If you liked Wish You Were Here you’ll love …

Copyright

About the Publisher

This is the true-life Hi-de-Hi! story of the Butlin’s girls – the women who worked at Butlin’s holiday camps during the company’s Golden Age, from the opening of the first one at Skegness in 1936 to the 1970s when they were in their prime, before the growth of cheap air travel and overseas package holidays sounded their death knell.

In Wish You Were Here we have drawn on interviews with many of the legendary Butlin’s redcoats, but we have also spoken to waitresses, bar staff, chalet-maids, chefs, kitchen porters, office staff, security men and the many other staff who kept the camps running, as well as to holiday-makers who loved Butlin’s and returned there year after year.

Many redcoats also returned season after season, and some married other redcoats and built their lives around Butlin’s. Others were merely passing through, but even then, they often took away with them experiences and memories that they would draw on and treasure for the remainder of their lives.

The camps began and thrived in an era when – true to their caricature image – seaside landladies really did kick their guests out straight after breakfast and often did not allow them to return until 5 or 6 p.m. Billy Butlin always claimed that the idea for his holiday camps came from the sight of dejected holiday-makers traipsing along the streets of Barry Island under leaden skies while they waited to be allowed back into their ‘digs’. ‘I felt sorry for myself, but I felt sorrier for the families with young children as they trudged around, wet and bedraggled, or forlornly filled in time in amusement arcades until they could return to their boarding houses,’ he claimed in his autobiography, passing over the fact that he probably owned the arcades where these families were spending their holiday money.

Inspiration had struck and Billy began hatching the idea of resorts where holiday-makers could escape the British weather – and be entertained – all day, every day. Even better, his camp staff would also look after the children, no matter how young or old, leaving parents free to please themselves for possibly the only time all year.

Billy Butlin was already rich and successful when he launched his holiday camps. The son of an ill-matched couple, he’d had a restless upbringing. His mother came from a family of travelling showmen, but his father was the wastrel son of a wealthy family, a ‘remittance man’ who went into voluntary exile in South Africa in return for the allowance paid by his long-suffering relations. The marriage soon ended and Billy’s childhood was spent moving between South Africa, England and Canada. His education was sketchy at best, but he was quick-witted and hard-working.

He enlisted in the Canadian Army in the First World War and then worked in a department store before returning to England in 1920, working his passage on a cattle ship. He made his way to his showman uncle’s winter quarters near Bristol and used his last thirty shillings (£1.50 then and about £75 today) to rent a hoopla stall from him at the first fair of the season in a boggy Somerset field. Unlike most showmen at the time, whose prizes were so infrequently won that the metal ones often had to be cleaned to remove the rust, Billy’s were relatively easy to win. That, together with the free advertising of prizes branded with the Butlin’s name being carried around the fairground by the winners, acted as such a successful promotion for his stall that he made ten times the profits of his rivals.

He expanded rapidly, and by the end of the 1920s, he was operating a string of arcades, amusement parks, fairground pitches and zoos all over the country. He was an inveterate gambler, always willing to back his instincts and hunches with serious money, though not all of his gambles succeeded. He lost his pride and joy, a beautiful American limousine, in a card game. He won it back the next night, but then lost it again on a toss of a coin. However, his gamble on holiday camps – he borrowed to the hilt to launch his first at Skegness and nearly went bust before it opened – paid off in style.

The boarding house keepers with whom Billy was competing were often their own worst enemies. Quite apart from driving their guests out from morning till evening, many charged the holiday-makers extra for anything they used. Having a bath was invariably subject to an extra charge and some boarding house keepers even charged for the use of salt and pepper.

Billy Butlin had set his prices at a level he believed working people could afford, coining the eye-catching slogan: ‘A week’s holiday for a week’s pay’. That included accommodation, three full meals a day and free entertainment, for an all-in price of from £1. 15 s to £3 a week, depending on the time of year, the equivalent of £90–£150 today. The slogan was slightly misleading, since the price was per head, so for a family of four, the breadwinner would have needed almost a month’s wages to pay for a week at Butlin’s.

The very first Butlin’s holiday camp, at Skegness, opened in 1936. Billy already had a large amusement park in the town and knew the area well. He chose it partly because of its good transport links and closeness to several major urban centres, though the cheapness of the land and the small local population – meaning fewer people to object to his plans – must also have been influential factors.

After scouting the coastline around the town for weeks, Billy Butlin found what he was seeking: a 200-acre turnip field at Ingoldmells, a couple of miles outside of Skegness. Having bought the field, he set to work. He designed the camp himself, sketching plans and jotting ideas on the back of cigarette packets. His background as a showman was evident in his chosen designs – like a fairground, the camp was to be awash with bright lights, vivid colours, music and noise, but there was to be a kind of glamour, too. The main buildings were arranged deliberately to evoke the great ocean liners of the era, regarded as the height of sophistication. Painted brilliant white with coloured detailing, the buildings formed a line with a tower in the middle, echoing the bridge and funnel of a liner.

Billy’s original aim had been to create a camp for 1,000 people with 600 chalets, but it proved so successful that before the first season was out, the capacity had to be more than doubled and it eventually accommodated close to 10,000 holiday-makers. Some of the chalets even had bathrooms, but the majority of holiday-makers had to use communal bath houses and toilet blocks (though even those were a step up from the slum housing in which many still lived).

Campers were made to feel welcome from the moment they arrived. As the buses bringing visitors from the station pulled up inside the camp, a tannoy announced, ‘You have now arrived at Butlin’s holiday camp. We hope you had a pleasant journey and that you will all be very happy here.’

Читать дальше

![Питер Джеймс - Wish You Were Dead [story]](/books/430350/piter-dzhejms-wish-you-were-dead-story-thumb.webp)

![Brian Thompson - A Monkey Among Crocodiles - The Life, Loves and Lawsuits of Mrs Georgina Weldon – a disastrous Victorian [Text only]](/books/704922/brian-thompson-a-monkey-among-crocodiles-the-life-thumb.webp)