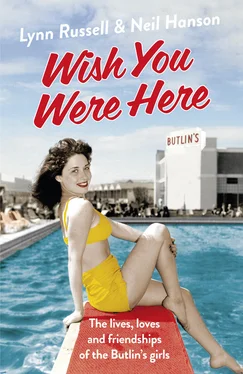

To help them achieve that happiness, Butlin’s Skegness was lavishly equipped with a theatre, a Viennese dance hall, a beer garden, a fortune teller’s parlour and Ye Olde Pigge and Whistle – a half-timbered mock-up of an Elizabethan inn. The landscaped grounds contained rose gardens, a swimming pool with cascades and a fountain, a boating lake and all sorts of sports facilities.

Billy was also one of the first to recognise the commercial possibilities of the emerging celebrity culture. He hired the aviator Amy Johnson – a national heroine after making the first ever solo flight from England to Australia – to attend the opening ceremony of the Skegness camp, and when the cricketer Len Hutton scored a record 364 against Australia in 1938, Billy paid him £100 to appear on stage with a bat made from sticks of Skegness rock while Gracie Fields bowled to him. The champion boxer Len Harvey was also paid to spar with a boxing kangaroo.

However, when the camp first opened, it seemed as if Billy’s grand plan was going to be a failure. People in that era were often quite shy and reserved, and ‘showing off’ or ‘making a spectacle of yourself’ were frowned upon. Almost everybody wore their best clothes when they went to the seaside, and most people didn’t go swimming in the sea at all, though paddling in the shallows with their trousers rolled up or their skirts lifted a decorous few inches was quite acceptable. As one female holiday-maker recalled, ‘Everybody used to point and stare when people came onto the beach in a swimsuit. It was terribly daring to have a swimsuit on at all!’

As Billy walked around the camp, he noticed that very few of those first campers were using the facilities or taking part in the activities. Most of them were keeping themselves to themselves and many looked bored. Desperate for a way to liven them up, Billy asked Norman Bradford to take on the task of cheering up the campers. A gregarious, outgoing character with a good sense of humour, Norman took to his task with gusto, chivvying the holiday-makers into joining in with the activities, putting on a free drink or two to loosen everyone up and keeping them entertained with a string of corny jokes. Norman also claimed to be the originator of the ‘Hi-de-hi!’ catchphrase, to which his audience would respond ‘Ho-de-ho!’

Within a very short time of these innovations, the camp was beginning to buzz. With his characteristic willingness to back his hunches, Billy decided that if British holiday-makers couldn’t enjoy themselves without outside help, then he would employ an army of helpers to make sure they did. They needed a uniform to make them instantly identifiable, so Billy bought a job lot of red blazers; the Butlin’s redcoat had been born.

Despite the hoary old joke that was soon circulating among Butlin’s campers – ‘I’m going to join the escape committee’ – most people seemed to like being told how to enjoy themselves. Many of them had more than enough things to worry about during the rest of the year and actually relished letting someone else take the strain of organising their holiday activities for them. And if they didn’t want to do something, they could always say no, although they needed to be strong-willed, because the redcoats could be very persistent.

Billy was quick to spot problems or opportunities and even quicker to take advantage of them. ‘Can’t’ was not a word to be found in his vocabulary, as the Butlin’s archivist and former redcoat Roger Billington discovered when Billy decreed that water-skiing should be made available to campers at Minehead, and put Roger in charge of organising it.

‘But we’ve never water-skied before,’ Roger said. ‘We’ve never even taken the speedboat out.’

Billy gave him a withering look. ‘There’s a library in Minehead, isn’t there? Well, get a book on it.’

None of the activities we now identify with Butlin’s was invented by its founder. All of them – mass catering, resident entertainers, chalet patrols, semi-compulsory jollity and participation enforced by perpetually smiling staff with a ready stream of catchphrases – were features of the smaller holiday camps that had existed since the later years of the previous century, and of those camps owned by Billy’s business rival, Harry Warner. Still, Billy made them seem new by practising them on a scale never seen before and promoting them with all his showman’s chutzpah and razzle-dazzle.

His formula fitted a ready-made gap in the market, but he also benefited from a piece of very fortunate timing. Until 1938, only two million Britons were able to afford to take an annual holiday and most of them were middle- or upper-class people for whom Butlin’s all-in, all-mates-together style of entertainment was likely to be anathema. However, in that year, the Government passed a bill compelling employers to provide all full-time employees with one week’s paid holiday a year. At a stroke, the number of Britons able to afford a holiday trebled to six million, and many of them, mostly skilled and unskilled working people, began finding their way to Butlin’s.

Not even the outbreak of war in 1939 – just three years after he had opened that first camp, when his second at Clacton was only a year old and the third, Filey, not even completed – could ruin Billy or derail his ambitions. When war was declared, the camps were acquired by the Government as military bases. The Army took over Clacton, the Royal Air Force got Filey and Skegness was taken over by the Navy and rechristened HMS Royal Arthur .

Billy also had to make a wartime alteration of his own. In the late 1930s, the targets on the shooting range at his Bognor amusement park were effigies of Nazi leaders: Hitler, Goebbels, Goering and von Ribbentrop. After the retreat from Dunkirk in 1940, however, with a German invasion now expected at any moment, Billy Butlin hastily arranged for the targets to be removed, lest invading Nazis should catch sight of them and decide to use Butlin himself a target.

At the instigation of his friend General Bernard ‘Monty’ Montgomery, Billy was also hired to provide entertainment centres for soldiers on leave and to construct new military camps at Ayr in Scotland and Pwllheli in North Wales. Like his existing camps, he negotiated a deal for each one, which allowed him to buy them back at the end of the war at a knockdown price. With a hasty refit and a lick of paint, Butlin’s was ready to accept holiday-makers again almost as soon as the last shot was fired.

Billy Butlin’s camps proved hugely popular and hundreds of thousands of people flocked to them every year. Although changing times eventually saw them go out of fashion, causing many of the camps to close in the 1980s, the remaining ones have been reinvented and remodelled for twenty-first-century tastes. Three camps – at Bognor, Minehead and Skegness – survive and thrive to this day, and the name Butlin’s still evokes a smile of recognition in almost everyone, whether or not they ever went on holiday there themselves.

Wish you were here? Many still do.

Hilary

Hilary Cahill was in her late teens when she first heard of Butlin’s in 1957. Born in 1940, she grew up in Bradford in a solid working-class home. Her mum worked in Whitehead’s mill in the city and her dad was a foreman at Croft’s engineering works, so although they were never wealthy and lived in a back-to-back terraced house, with two good wages coming in there was always food on the table.

Her mum was a dark-haired, attractive and lively character. She absolutely loved to dance. It’s where Hilary got her own love of dancing from, because her mum taught her when she was small. However, her dad couldn’t dance to save his life. ‘He used to claim that it was because he’d never had any shoes when he was young,’ she says, ‘and only had boots, but that sounded like a bit of a lame excuse to me. He was still using the same excuse when I was a teenager! My mother and I tried to teach him over and over again, but whatever we tried, it just didn’t work. He had two left feet and that was the end of it! All the mills used to have these big dances once a year and we used to go to all of them, dressed in our best clothes. The real top bands used to play at them, so they were great. My dad used to hate it, though, when we all went to the works’ dances and my mum would be dancing away with people while he was just sitting there, looking on.’

Читать дальше

![Питер Джеймс - Wish You Were Dead [story]](/books/430350/piter-dzhejms-wish-you-were-dead-story-thumb.webp)

![Brian Thompson - A Monkey Among Crocodiles - The Life, Loves and Lawsuits of Mrs Georgina Weldon – a disastrous Victorian [Text only]](/books/704922/brian-thompson-a-monkey-among-crocodiles-the-life-thumb.webp)