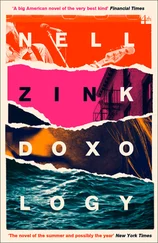

One afternoon Meg saw out the window that a large red tanker truck was backing through the courtyard, right over Karen’s mouse town. The town for mice was something between a garden railway and the Lilliputian village in Mistress Masham’s Repose . It was small and inconspicuous, being modeled on the county’s towns of one or two stores each. It was very childish and in Meg’s view due for destruction, but still the truck went right over it like it was nothing.

Meg marched outside, said “Excuse me,” saw the driver’s face, and marched back inside shivering. She knew that face. She even knew the name on the truck: Fleming. FLEMING’S OIL, GAS, AND PROPANE.

The driver had been a junior garbage man at the college, one of the kids who rides on the side of the truck, strong enough to heave full trash cans higher than his head. As he lowered his hose into Centerville’s oil tank, Meg sat down on the kitchen floor with her back to the cabinets. There was no sign that he had recognized her.

“Mrs. Fleming?” he called out. “That you, Mrs. Fleming?” He knocked on her back door and tried the knob, but didn’t come in. Cha Cha started yapping. One last time he called out, a little louder, “Mrs. Fleming! That you? I ain’t going to hurt you.”

Meg made herself very small and pressed into the corner under the sink. He opened the door.

“I’ll be damned,” he said. “I know you from Stillwater.” Meg hyperventilated and hugged Cha Cha tight. “I’m pleased to see you. People was worried. Running away like that, taking y’all’s kid. People thought you had ended it all.”

“Just get out of my house,” Meg said.

“That ain’t going to help you,” he said. “I’m looking right at you. I ain’t going to forget I saw you.”

“And can I do something for you? What do you want?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Nothing, probably. I’m just surprised. I couldn’t believe it. I wanted to make sure it was you. Now I’ll be on my way, if you don’t mind. I got deliveries to make. Good day to you.” He tapped his fingernails on the counter and didn’t turn toward the door.

Briefly, Meg thought of cash. Then she remembered something more likely to keep him quiet. “You like to get high?” she asked, getting to her feet and putting the dog down.

“Do I like to get high,” he said. “Do I like to get high.”

“I can see that you like to get high,” she said. “You want to be my partner in crime? If you would step outside for a moment. You don’t want to see where I keep my stash. It’s personal.”

“I’ll be right outside here,” he said.

Meg unfolded her little magnesium stepladder so she could reach the inaccessible cabinet over the fridge. From it she removed a pressure cooker containing an ungodly number — a highly illegal number — of Baggies filled with white powder, enough to get her forty years in the pen, and removed four Baggies. Then she rummaged through her hardware drawer until she found her.38. She called out, “Just a second!” Her ammo was in the next room, locked in a desk drawer. But would she have fired it?

She decided she didn’t need the ammo, because she wasn’t about to shoot anybody in her own kitchen.

It was a spontaneous sense: Don’t shoot him in your kitchen.

It proved that at last she had become truly black inside. Her mother would have shot a strange black man in her kitchen and called the cleaning lady before she called the coroner. But Meg wasn’t so sure she could get away with it. She even considered the effect on the man’s family, needing his income.

She waved at him through the window to come back inside.

“This is it,” she said, pointing the gun in his general direction and handing him the drugs. The gun was heavy and she wondered if she could have hit anything she wasn’t actually touching with the muzzle. Not that it mattered. “That’s all there is. There’s no more where this came from. Once a year, when you deliver fuel oil. That’s it.”

“Twice a year!” he protested. “You people use up a lot of oil down here. You should try to save on it sometimes. Y’all keep y’all’s windows open all winter.” He put the Baggies in his pocket and politely tipped his welder’s cap.

He was tempted to take the gun, but he was unsure whether it might not be loaded. He recalled that Mrs. Fleming was crazy.

Two hours later, he was dead. He had greatly misjudged the speed of an oncoming dump truck as he made a left turn from a stop sign. The other driver also died. Even the drugs and Baggies burned, leaving no trace.

He was already two counties away, so Meg never heard about the accident.

She was scared of him for months. Visibly scared, as in jumpy. But not rational jumpiness, the kind that makes you pack your stuff and head for the hills. She put the fuel truck driver out of her mind — so far out she couldn’t get at him — and worried about things she could talk about with Dee. Temple’s love life. Karen’s grades.

Gradually her fear faded to the existential angst that incessantly haunts all mankind in modernity.

The existential angst served to mask her fear of Lee. The angst was: That you only live once. That you shouldn’t waste your youth. She had no lover, no close friends, no underground theater group to perform her self-censored plays. She had to fake poverty to keep the fuzz off her back. If she wore stylish clothes or drove a reliable car, social services would get suspicious. She didn’t spend enough time honing her craft. Et cetera, ad nauseam. It was the worry about not making the most of herself. The thing that troubles nearly all of us, nearly every day.

The fear of Lee was: That he would catch up with her, turn her child against her, wring her heart out like a dishrag, confront her with Byrdie, make her loathe herself, and get her in trouble.

That fear of Lee was useful to her, because it served to mask a deeper fear. One she never feared consciously, because it was unfearable. There was no way to shoehorn it into her emotions, and thus it could not be properly feared — the same way unthinkable things (such as potentially causing an accident by giving an on-duty driver enough drugs to fuck up a twenty-mule team) can’t be thought.

The unfearable fear was: Here she was, on her own with a little daughter entirely dependent, surviving in a way that could get her sent up for a near lifetime, or even killed.

And all to protect herself from what? From Lee’s emotional manipulation, her powerlessness in a relationship? From being looked down on?

Risking her freedom and her life, the only life she would ever have.

Lee had given her a choice between eviction and therapy. So basically the worst he would have done was throw her out. No way on earth she would have let herself be cornered into getting committed. So the worst-case scenario with Lee was — literally — that she might have to live somewhere other than Stillwater Lake, and miss her kids.

And the worst the state would do with her, if it found that pressure cooker? The worst Lomax might do, if he learned of her mutual blackmail with the driver? He was protective of his supply chain, his income stream, his inventory, his privacy.

Imagine the look on Karen’s face, watching Meg be taken away in handcuffs, never to return. Or coming in after school, past the corpse of Cha Cha, to find her tied up in bed with a piece of her head missing.

Or rather, don’t imagine it. Meg never did.

When a different driver showed up for the next fuel oil delivery in a different truck, she knew she had been wrong to worry, even unconsciously. She received cosmic reassurance that she would always survive.

O n Byrdie’s arrival at the University of Virginia, he was tapped for a secret society, the FHC. Its strict conditions of membership do not permit disclosure of its ritual practice, but suffice it to say that Byrdie had a sheaf of FHC letterhead and used it to write poetry. He liked “Acquainted with the Night” and “Tears, Idle Tears,” so his poetry was generally composed of old-fashioned scholar-and-gentleman-type rondos and villanelles on philosophical themes. He showed it to a girl he liked, and she became his lover — a third-year suburban brunette with thigh-high socks and formal training in vocal jazz who swam sixty laps a day. Her praise of the poetry was so effusive that Byrdie showed it to Lee. In the aftermath Lee did not shoot himself, but in silently disavowing his once-perfect son called out one of the great hangovers of our time.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу