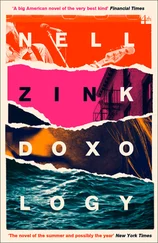

Diane told Meg to stop by for coffee if she was in the neighborhood, and Meg lied that she would.

Two days later, Meg heard the slurping sound of tires in the mud and peered around the window shade to see Diane emerging cautiously from her car. She went out to meet her.

Diane sought a political favor. She wanted Meg’s support at a public hearing. “We want the board of supervisors to apply for a grant to build public housing,” she explained. “Some people in this county live in conditions I just can’t believe. Especially black people, no offense. It’s not sanitary.”

“My people, the black race,” Meg said, offended. “We got one thing in common. And that’s that we’re exactly like the white race. The white people around here don’t live in a housing project. Why should we live in a housing project? We never did before. We have our own driveways now. We just need better houses.”

“Not if you can’t pay for it,” Diane said. “People living on squatters’ rights have no equity. To fix up a house, you need a loan. We can’t just give you the land. It wouldn’t be fair, when the taxpayer has to pay cash. I think moving to a town is a fair trade for not seeing your kids go barefoot to the outhouse.”

“I don’t think of this as an aesthetic issue,” Meg said.

“I didn’t say it was aesthetic,” Diane said. “It’s pretty swampy there now, but what are we going to do? Put a housing project on good farmland that’s already drained? No offense.”

Just a few months later, Meg’s shack was inspected and condemned as unlivable. Not remotely up to code. A contractor would be paid to tear it down. In its place she was offered AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children), food stamps, and cheap rent in the housing project to be known as Centerville.

Meg and Karen moved to Centerville the summer before Karen started eighth grade. Temple Moody now lived right across the courtyard.

It was a one-story complex, built on a slab, with a minimum of nails and wood that hadn’t cured. You could reach up and pull the siding right off. That looseness kept the air circulating between the siding and the tar paper, which was important in such a damp environment. The newly drained soil was still putting out huge cabbage-like foliage that covered the courtyards between the wings of the building in an almost impenetrable thicket, with pigweed six feet tall by April.

For Karen, Centerville held endless pleasant surprises: Neighbors. Playmates. TV. Telephones. Flush toilets. Long, hot showers. The paradise that is modern life.

It even had a little shopping center across the road, with a Greek restaurant (self-service, with gyros on the menu as “Mexican Taco”) and a florist.

At first Meg continued to do business with Lomax at her old place, uneasy about her new lack of privacy. She had graduated over the years from collecting mushrooms to warehousing bales of pot for over a week in exchange for sums in excess of two hundred dollars.

It was risky — the bales were fair size and fragrant — but at her old house, it had worked fine. There she had no neighbors and a moat. Almost nobody ever stopped over but Lomax, and Flea kept careful watch. But there was no question of continuing in that line. You can’t stash pot in an empty house. Sooner or later it’s going to get ransacked. And you most certainly can’t carry bales of homegrown through a federally subsidized housing project. There was no driveway in Centerville, just a busy parking lot. Who was Flea going to watch out for — everybody? Meg had to move up in the world.

Lomax had already made his career move. A childhood friend had looked him up. This was a man known as “the Seal” because he was AWOL from being a Navy SEAL. For years he took it out on the navy by running his speedboat out to the mothball fleet with a grappling hook and stealing vital parts for scrap. That was more gratifying than it was lucrative. More lucrative was a connection he made in a waterfront bar in Yorktown while eating raw clams in an informal contest that proved to all present that he was made of sterner stuff than most men. One of the losers told him there was major cash to be made by someone with the cojones to transport certain bundles to a certain parking lot in Newport News. These were to be found strapped in inner tubes on the beaches of the barrier islands of the Eastern Shore. They originated in Colombia and had been dropped from airplanes.

The Seal was game to try it, but not naive. He agreed to take the job, but privately he planned to bring the bundles only as far as Poquoson, there entrusting them to Lomax, who would drive them to Newport News.

Once a month thereafter, Lomax accepted a package and payment in advance from his dear old friend. He sat down in Crosby Forrest’s seafood restaurant to wait, and Flea drove the bundle an hour, past stoplight after stoplight, past the MPs manning the gates to the naval shipyard and the air base, and heaved it into the bed of a pickup in a certain parking lot. It was that simple.

Then they got into a discussion about street value, and they got creative.

That was Meg’s career opportunity.

The next shipment was two bundles. One went into the bed of the pickup as usual, and the other, smaller one went to Meg’s apartment in Centerville. She didn’t do much with it. Mostly it just sat there like utilities stocks, paying dividends. All she had to do was measure level tablespoonfuls into Baggies. She worked during the morning, by natural light, so matter-of-factly that passersby would have thought she was bagging sugar cookies for a bake sale. Sooner or later Lomax always dropped by to pick them up.

She was making enough money to think about the rainy day when she would blow out of there. She was of two minds about where she wanted to retire. Something about her current profession made her value the ethos of a hacienda in Mexico. But as a writer, she still aspired to make it in New York. Plus she didn’t feel it would be fair to Karen to move her to Spanish-speaking schools.

She subscribed to Writer’s Market and queried five agents about her play The Wicked Lord . They all said the most interesting character dies too near the start. She reacted by writing a play in two days and a night about a utopian lesbian commune defending itself from real estate interests. The villain saved his appearance for the end. The lesbians became the bacchants of Euripides, killing him in a festive manner.

It was gripping and seemed to write itself. But she knew you can’t publish material like that.

She outlined a romance novel set in colonial Virginia, with a ghost, called Blame It on Beldene. The draft ended on page fifteen.

As a writer, she was struggling. As an accomplice to the wholesale drug trade, she was setting new benchmarks for excellence in felony crime.

The combination of relative prosperity and a mailing address (the shack had not enjoyed rural free delivery) allowed Meg to money-order books from catalogs. Karen routinely appeared with Temple in tow to beg for Newbery Medal winners. Temple would point out that with two children reading each book, it was effectively half price.

Meg had mentally adopted Temple the day she caught him outside watching her type. As he entered her bedroom she perceived his spontaneous awe of her Olivetti’s all-powerful machinery, the medium through which Logos becomes the printed word — their shared ideal. He lifted it as gingerly as a rifle and admired its dark curves like a tiny Steinway. She let him type a little. He left clutching an Ezra Pound couplet as though it were a fifty-dollar bill. There was something very inspiring about Temple. He made her think literature mattered.

His parents, now her neighbors, were soon her friends. His mother, Dee, turned out to be an unflappable realist quite to Meg’s taste. She had taught second grade before they closed the black schools. She had lived for thirty years in her husband’s hereditary compound before rural renewal took it away. Yet she despised nostalgia in any form.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу