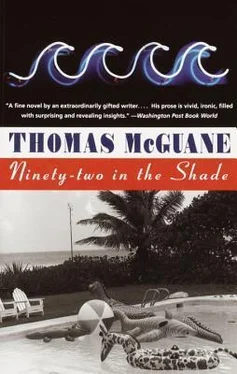

Thomas McGuane - Ninety-Two in the Shade

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Thomas McGuane - Ninety-Two in the Shade» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ninety-Two in the Shade

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ninety-Two in the Shade: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ninety-Two in the Shade»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ninety-Two in the Shade — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ninety-Two in the Shade», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Why didn’t you go home!”

“Oh come on.” His father’s detachment was serene. If there was anything that identified him by blood in place of the dissimilarity of hands, it was this proclivity for slipping the moorings. Skelton’s own “ordeals,” as his father termed them, his attempt to be sane, a biologist, when his actual instincts were less linear, less useful, only led to a bout of hallucinations, featuring drowning, falling, wild horses, endless crowds of driverless automobiles under evidently perfect control hurtling over rough landscapes; and even before Dance had spoken of Charlie Starkweather in the city jail, electrocution, which came to him as a kind of tickling to death, a trampling under electrical horses.

“My first instinct was that this face-off with what’s-his-name was a matter of honor.”

“Oh God!”

“Well, you’ll admit that was the obvious choice.”

“I don’t admit that!”

“Well you goddamn prima donna! What was the obvious choice then!”

Skelton racked his brains. His father was right. But he didn’t have a thing to tell him.

“That’s the best I can do,” he said, not quite coming clean.

“All right then listen you dumb bunny. Now you can get killed at this thing you’re up to. So, you see it through so you know what it is when it comes. Otherwise you are a bystander and nothing could be more disgusting.”

They stopped talking. Skelton remembered in his childhood his father explaining to him that he lived in a civilization that was founded from its family life to its government on the principle that the wheel that squeaks the loudest gets the grease.

“Your grandfather,” he said now, “is a great American in the way he has learned to work the gaps of control that exist between all the little selfish combines. That is why he has been able to rook the country out of millions without ever getting petty about it. — Now, at my best I have been a transitional figure in trying to get you some idea of his energy and coordinational power — with the conviction that I would be consumed in the process — so that you could use it toward something a little more durable than the kind of power your grandfather has craved so … horribly.”

He took up his fiddle and all that scarifying instinct for spirals upon spirals of cognition fell from his tormented face; and a turbulent gaze into emptiness that had become less Skelton’s birthright than a kind of visitation fell across it. For Skelton’s father always felt himself to be poised on the edge of some yawning fissure. One of the ways he crossed it, besides the sports page and its illusion of a constant skein of clear athletic effort in which no one was swept away in time, one of the ways he crossed that fissure was with his fiddle. His head inclined upon it now as though he would fall serenely asleep; the eccentrically long bow indented itself gently against the strings and paused before the opening strains in deepest space. And then the crazy man began Jerusalem Ridge pure and howling in a final elevation to the light that Skelton could understand.

* * *

Skelton thought about the electrical drill and how it could take the hole of the light socket and modify it to another; hole power; perhaps ridiculous but close to his father and his mysteries. He thought of the vultures you could see circling a pit (usually filled with garbage but never mind that); or how during the eclipse of the sun in 1970, running to the Snipe Keys, he had stopped the skiff when the light started to go out, looked up as proscribed by radio news broadcasts to see half a thousand seabirds circling a black hole in the sky. It was the kind of hole people could create, throwing each other into shadow. But there was something there to be considered, the radios everywhere telling you not to look, the vultures over the garbage pit, the news broadcasts of 1970 reflecting another eclipse and a quarter of a billion people staring into the black hole in the sky. And in his own fractional quadrant of world, Skelton looking to the whirling seabirds and their black pivot and then across the still, mercurial sea darkening as though oxydized by this lunar tropism. The power of nothing.

* * *

His father was laughing, half to himself. “Four nights ago, I got particularly drunk with these fellows that work the boats, then bum their way up to the Carolinas in the summer. I left them about midnight I suppose and was crawling, literally crawling, along Eaton Street when a car pulled up and Bella got out. She took about fifty pictures of me creeping down Eaton in my sheet, saying, “Bahyewtiful, bahyewtiful!” the whole while. I suppose she’s fanning them out for the old man right now. That won’t take him in! He’s seen it all … By the way, he knows your plan and completely disagrees with my interfering.”

Skelton thought, That does not surprise; any more than that his father, who had eschewed authority in himself as well as others throughout most of a lifetime, should suddenly attempt to advise and force, however halfheartedly; while his mother, who cultivated durability as another might table manners, was beginning to discover an exasperation with all three men, as anyone would with cheap or highly tuned machinery that constantly needed repairs.

“Well, I don’t know what I wanted to tell you. I’m so down now it seems like I could tell you more about what might await you. Even my veins feel slack. And I’ve only gotten to that place where everything is ironic in a simpleton’s way; you know, looking down at people living beyond their means, ridiculing bad taste and so on. That’s not very interesting. So I haven’t got much to tell you. Except that I wish you’d give up this idea.”

“What would you do in my place?”

“I’d go through with it.”

“That neutralizes your advice.”

“No it doesn’t. I have a perspective that I couldn’t have if it was me acting.”

“Like what kind of perspective.”

“A Christian one.”

“Why couldn’t I have that myself?”

“Because the Christian perspective is one that only obtains in the third person; otherwise it vanishes in egotism and you become a figure from which ridicule can derive as from Christ himself.”

“Well, let me say first of all that I don’t believe that for a minute. And then let me remark that when a man goes to such trouble to set up a crisis, I have a certain duty that comes of my respect for him to let that crisis take place.”

“I’d say, on the basis of that, that you were a smart little fuck. But I think you’re just reacting by temperament and out of your nose for trouble.”

“Anyway, it never got me anywhere except a trip to the ward until I started acting on my own instincts and following through. Now what I’m doing and what Nichol is doing are two cases of just exactly that.”

“Are you quite sure?”

“No, I’m really not.”

Skelton was getting tired of this; and he could see his father was too. So he asked his father to get up and come to his place; and surprisingly he bounded out of bed, the fiddle familiarly in one hand like a tennis racket.

They entered the fuselage, the first time for his father; he beamed around its interior and began dressing as Skelton handed him articles of clothing.

Skelton quite suddenly recalled Nichol Dance. Let’s think about this thing head on now. It has become clear that I am liable to forfeit, as they say, my, you know, life. What you get in that case is … death. Now: what can I expect in the way of a tremendous death? Not much. There are no tremendous deaths any more. The pope, the president, the commissar all come to it like cigarette butts dropped to the sidewalk from the fingers of a pedestrian hurrying on toward some cloudy appointment.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ninety-Two in the Shade»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ninety-Two in the Shade» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ninety-Two in the Shade» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.