Patrick wasn’t much interested. He said, “Well, when I get something to breed, I’ll take a hard look at him.”

“I want you to breed that old Leafy mare. This stud of mine is young and he needs mares like that to put them good kind of babies on that ground. You know how long Secretariat’s cannon bone is?”

“Sure don’t.”

“Nine inches. So’s this colt’s. That’s what makes an athlete. That’n a good mind. This colt’s got one of them, too. His name is American Express, but I call him Cunt because that’s all he has on his mind. He’s a stud horse, old Cunt is. But I’m like that. You were always lookin for a smoke, I’d call you Smoke.”

“What d’you call Claire?”

“Claire sixty percent of the time, and Shit when she don’t get it correct, which is right at forty.”

Patrick thought, I wonder if they’ll ever teach him English. Maybe he doesn’t want to learn. Maybe you can’t be an old buddy and speak English. Patrick would rather hear a cat climbing a blackboard. And he didn’t like what Tio called his wife forty percent of the time. In fact, he just didn’t like Southwesterners. It wasn’t even cow country to Patrick. It was yearling country. There were no cowboys down there significantly. There were yearling boys and people who fixed windmills. After that, you put in dry wall on the fourteenth story of a condo in Midland, where some cattleman did it all on a piece of paper with a solid-gold ball-point pen and a WATS line: a downtown rancher, calling everything big he had little and old, and calling his wife shit; the first part of the West with gangrene. Dance the Cotton-Eyed Joe and sell it to the movies.

Here came Jack Adams with another bourbon; probably spotted that look in Patrick’s eye and sought to throw fat on the fire. People often have this kind of fun with problem drinkers. But Patrick was determined to be somebody’s angel, and they wouldn’t catch him out today. Instead he started back to the company, excusing himself. Made a nice glide of it.

Deke Patwell and Penny Asperson were passing a pair of binoculars back and forth, trying to find the property lines a thousand yards uphill. “Not strong enough,” said Deke, putting the glasses away. “We’d have to walk up there, and we know how we feel about that.” His mouth made a sharp downward curve.

Anna said, “We use the National Forest anyway. So I don’t know what that property line’s supposed to mean.” She gave the Bloody Marys a thoughtful stir.

“You will when the niggers start backpacking,” said Deke Patwell. “Oh God, that’s me being ironic.”

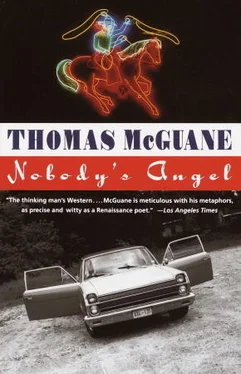

“Anna’s the lucky type,” Patrick said. “She’ll get O. J. Simpson and an American Express card.”

Claire said, “You sprinkle this much?”

“After July,” Anna said. “It’s a luxury but we’ve got a good well. If it was Jack, we’d be waist-deep in sage and camass and just general prairie, and the ticks would be walking over us looking for a good home.”

The buildings, which made something of a compound of the lawn, moved their long shadows, lengthening toward the blue sublight of the spruce trees; but the real advent of midafternoon was signaled when Deke Patwell passed out. Everyone gathered around him as his tall form lay crumpled in his oddly collegiate lawn-party clothes. He was only out for a moment, which was too bad, because he had grown strident with his drunkenness, especially as to his social theories. He had been drawing a bright picture of Jew-boy legions storming the capitol at Helena when his eyes went off at an angle and he buckled.

Then he was trying to get up. He rolled mute, imploring eyes at the people surrounding him, threw up and inhaled half of it. It was like watching him drown. Jack bent over, stuck a hand in his mouth and said, “I’d say the Hebrews got the capitol dome.”

Anna said to Jack firmly, “Go inside and warsh your hands.” Deke let go another volley and said he didn’t feel so good.

Minor retribution crept into Patrick’s mind. He said, “Maybe a drink would perk you up.” Deke cast a vengeful glance up to him, said he would remember that, then tipped over onto one shoulder on the lawn and gave up. His plaid summer jacket was rolled around his shoulder blades, and a slab of prematurely marbled flesh stood out over his tooled belt.

Patrick ambled toward the little creek that bordered one side of the lawn. Perfect wild chokecherries made a topiary line against the running water, which held small wild trout, long used to the lawn parties. But then Penny Asperson followed him, and when he looked back, he caught Claire’s observation of the pursuit. In his irritation he thought Penny was thundering toward him. There were yellow grosbeaks crawling on the chokecherry branches, more like little mammals than birds.

“Bloody Deke,” said Penny. “If he’d had the gumption, we’d be up at the boundary. He’d be sober and the air would be full of smoldering glances.” Penny’s broad sides heaved with laughter. “ Now look. And he smells.” Patrick wished to speak to her of carbohydrates and chewing each bite twenty-seven times. But she was, after all, a jolly girl.

“The smell’s the worst of it,” Patrick said agreeably. “I thought Jack was courageous to free his tongue.”

“It takes a man to do that.”

“And Jack is a man,” said Patrick, a little tired of the silliness. A pale-blue moth caught one wing on the water and a cutthroat trout arose beneath it, drifted down-stream a few feet, sucked it in and left a spiraling ring to mark the end of the moth.

“Did you forget your rod?” Penny winked.

“Oh, what a naughty girl.”

“Patrick.”

“Penny. Let’s go back.”

“I think we should,” said Penny Asperson. “Or we’ll start talk.” They walked back to the tank, Patrick doing all he could to control his gait, to keep from breaking into a little jog. Tio was talking firmly with Claire, knocking her lightly in the wishbone with his drink hand, for emphasis.

As Patrick passed, Tio said, “Wait a sec, Captain. This goes for you.” Patrick joined them, trying to see just as much of Claire as he could with his peripheral vision. He wanted to put his hand on her skin. Tio went on in a vacuum.

“I need to have this little old stallion in motion,” Tio said. “I travel too much to keep him galloped, and besides, I don’t like to ride a stud. Cousin Adams tells me you can make a nice bridle horse, and if you can get this horse handling like he ought to, that’d be better than me having to mess with him every time I get off the airplane. You’re in the horse business, aren’t you?”

“Sure am,” said Patrick. Claire shifted her weight a little. “Can I change his nickname?” Claire reddened.

“You can call him Fido’s Ass for all I care. Just get that handle on him. I’m going in to look at old Jack’s artifacts. Supposed to have a complete Indian mummy he found in the cliffs.” He strode toward the house in his tall calfskin boots. “We gone try and give that mummy a name.”

Anna appeared in the door.

“Patrick!” she called. “You’ve got to take Deke home. He’s spoiled a storm-pattern Navajo and now he’s just got to go home.”

“Coming!” called Patrick, and Claire was halfway to the house — in effect, fleeing.

Patrick undertook the loading of Deke Patwell. Anna apologized for making Patrick accept this onerous detail, adding that otherwise it would have to be Jack and it was sort of Jack’s party. They locked Deke’s door where he slumped, and turned the wind vane in his face. His lip slid against the glass.

For the first couple of miles toward town, Deke tried slinging himself upright in a way that suggested he was about to make a speech. He slumped back and watched the hills fly by while the hard wind raveled his thin auburn hair.

Читать дальше