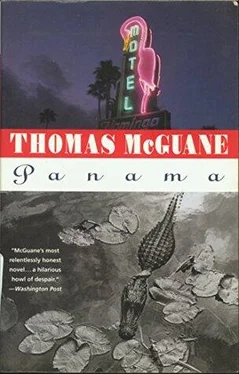

Thomas McGuane - Panama

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Thomas McGuane - Panama» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Panama

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Panama: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Panama»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Panama — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Panama», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Everything went off and left me,” Jim said.

They took me to Catherine’s on my release. There was no bandage around my head, no bump, nothing. I had had a concussion and was supposed to lay low. I had few impressions except that my eyes had grown small, the worst had been wished on me, I had found something out from Jim, and I was among the living. My dog was missing.

“I don’t know where she is,” Catherine said.

“Well, we’ve got to find her.” I told her to call the pound, tell them it was Deirdre, spots, white feet, missing. I was thinking of those men, their frayed nerves and the gas. There was no answer. I said run an ad. Catherine covered the mouthpiece.

“The paper wants to know what she answers to.”

“She doesn’t.”

She uncovered the mouthpiece and said, “Spots is the main thing I guess.” She hung up and came over. “Oh, darling, I love you. Get better. Stop being under such a strain.”

“I can’t seem to.”

“Of course you can.”

“Every time I try to relax, I start crying. I don’t feel like a grown man that way.”

“Where is it written you have to be a grown man?”

“All over the place.”

“It’s not.”

I could hear a shrimper’s diesel backing down at Brito’s yard; and the vacuum-cleaner sound of the bus. Catherine watched me steadily. I covertly tried to see if her eyes would shift; they didn’t.

“I looked at my new house,” she said. “It was lovely.”

“Oh, I’m glad.”

“Very carefully made.”

“Porch boards are sprung.”

“That’ll give us something to do.”

“And I’d like a wooden grill around the foundations so that cats don’t get under there and…”

“… and fight.”

“Yes, and fight under there all the time.”

“Yes.”

“They better find my dog. They don’t find my dog I’m calling Jesse.”

Catherine watched me, her eyes two stones in the mercury air.

* * *

Sometime later I awakened and Catherine was sleeping beside me, warmth radiating from her brown back, and I laid my face in the channel between her shoulder blades and pulled her thick curly hair around her neck so that I could look at the telegraph wires in the window. Warm moist air moved in a gentle mass over us; and across the way, a radio played a giddy weather report for the tourists. In the bottom of the window, laundry floated into my view. I felt like sailing with my love, feeling the centerboard hum in the wooden hull, the shapes of islands vault past our daydreams.

That or reviewing my life; but a good bit too much life reviewing has gone on already. The only wisdom it produces is the resolution to not do any further reviewing. My nose itched and I ground it against Catherine’s spine. She stirred and curved her bottom up against me; and then again, and then we were sleepily making love. When we were done, she turned and put her arms around me and her face against my chest and said, “Oh, darling, get well.”

The statement seemed to come from a very far place within her. I didn’t know exactly what she meant by it; but I felt, with great strength, that I wanted to give that to her. I wanted to get well. I just didn’t know what that was. If there was a fear, it was that I had never known; that I had been strikingly not well from the start; that my ticket to ride, such as it was, was based on the vividness of disease; and that I was paying for everyone else.

My first instinct was that a social life depended simply upon giving people what they wanted. So, I called Peavey, as a kind of test case.

I told him that I had finally understood that marriage was what Roxy wanted and that I therefore endorsed that view and would see Roxy that very day to make myself clear.

“Why, that’s very nice.”

“I am going to try to stop interfering,” I said.

“I think you should.”

“I am going to attempt to be normal,” I said, “eat regularly, see some motion pictures, and take in the hot spots on weekends.”

“Right…”

“And anyway, that’s all.”

“Well, that’s very nice. And look here, I’d like to return the favor. I got a line on your dog. I’ll have Nylon Pinder drop it by.”

“Say,” I said, “thanks a lot. I appreciate that. Nylon been feeding her pretty good?”

“Not too bad. Not too damn bad.”

“Well, that’s good, isn’t it?”

“A house pet should have special care,” Peavey said.

“Well,” I said, “I’ll be talking to you.”

“Real good, and thanks!”

Catherine was looking at me.

“I’m trying,” I explained. It was quiet.

She said, “You’re the original snowball in hell.” She was shaking all over.

11

MY UNCLE PAT was in his yard on a stepladder, out in the middle of the yard, wiring a creeper to a freestanding trellis. He was in some aerial relationship to the trellis, as though he, on his ladder, were feeding it like a tall bird.

“Pat, Roxy wants to get married.”

“I don’t care a thing about it.”

“I’m making my party at the Casa Marina a wedding party. But she wants to know if you’ll come.”

“I couldn’t say, Chet.” A bead of sweat fell from the tip of Pat’s nose sixteen feet to the ground.

“It’s going to be dressy as hell, Pat. And there’d, you know, be a ceremony.”

“But would I figure?”

“You’d have to work that out with Roxy.”

“It’d be good to have something other than Peavey’s henchmen and their trashy girlfriends.”

“That’s why I thought you might stand up for Roxy.”

“Can I dress?”

I hesitated, but not for long. Pat lived to dress up. It was the key to his attending. I said sure. He got happy quick and the ladder started over. He reached and embraced the trellis. They went down together in parallel. In the descending arc, I could see his happy eyes.

“I’m okay,” he said.

“The plant’s shot,” I said, looking at the turmoil of vines.

“I don’t have a green thumb,” he said. His mind was already on the wedding, his eyes glowing with yet unseen ceremony. I myself thought of the wedding, the orchestra, Catherine, semi-familiar faces, a warm and swollen ocean beaded with the lights of ships. I helped Pat to his feet, lost in happiness. I knocked loose dirt from his getup. “You’re a good uncle,” I told him, remembering the crazy angles of my father’s roof.

“If I could quit cruising,” he said. “People talk.”

* * *

Waiting in front of my house was a familiar man in safari clothes. His hair was slicked straight back without a part and he was chewing a cheroot.

“You are Ramón Condor,” I said, “star of The Reluctant Gaucho. ”

“The keys.”

“?”

“The check bounced on the Land-Rover. Get me the keys.”

“They’re in it.”

He walked over to the car.

“This was a go-anywhere vehicle,” he said, “now it’s nothing but a repo.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You’re a bald-ass liar and your checks are bum.”

“I knew only confusion.”

He was halfway in the car and he got out again. He flicked away the cheroot and cinched up his safari coat. “You knew only confusion…” He started at me. There are those who despise my flair for language.

I saw another smack coming and I lowered my head between my shoulders for protection, simultaneously turning my false-tooth-filled mouth to one side. But then when he got to me, I reflexively popped him in the side of the head and he sat down.

“This whole deal is getting highly Chinese,” he said.

“Don’t be coming at me like that.”

“I oughta leave you for the birds.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Panama»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Panama» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Panama» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.