Half the people I knew had taken a Coast Guard exam and become “captains.” Couples became captains together. I’d look in the phone book for old acquaintances and there they’d be: Smith, Captain Bill and Captain Sherri. I began to imagine a community where all were captains. Of course, many of these were realtors, though it was not out of the question for cosmetic surgeons or optometrists to be captains, too. It was very democratic, a homogenous world of captains.

Otherwise, my general impression was that Cayo Hueso had become part of New York, and not my favorite part. That would be the departure lounge at the airport. The same in-your-face style in the stores, the same goofy restaurant posturing so annoying to anyone who’s merely hungry. Furthermore, Key West was having a waste-management crisis with grimly amusing results, like the notorious Mount Trashmore, towering over the Key West Memorial Hospital and often cited in speculative considerations of the remarkably high rates of multiple sclerosis among its employees.

But Key West has always been changing. Patrick Hemingway, who grew up there before my time, told me that when he went back after a long absence he was stunned by the impact of the overseas water aqueduct. He remembered Key West as “a goony bird island,” a tropical, weather-blasted rock with humanity clinging to it in suitable humility. He marveled, too, that the black community in which he had so many childhood friends had missed the boom and was either disbursed or living in degraded vassalage to the tourism industry.

I certainly had seen enough. But it remains an odd pleasure to revisit these snapshots of the good times. There is nothing to compare to my years in the Keys as a reminder that Janis Joplin had it right: get it while you can. After that, it’s too late.

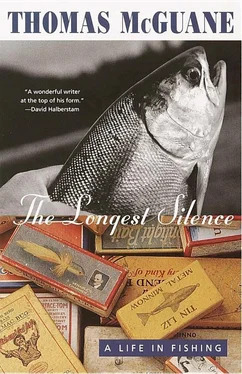

WHAT IS MOST emphatic in angling is made so by the long silences — the unproductive periods. For the ardent fisherman, progress is toward the kinds of fishing that are never productive in the sense of the blood riots of the hunting-and-fishing periodicals. Their illusions of continuous action evoke for him, finally, a condition of utter, mortuary boredom. Such anglers will always be inclined to find the gunnysack artists of the heavy kill rather cretinoid, their stringer-loads of gaping fish appalling.

No form of fishing offers such elaborate silences as fly-fishing for permit. The most successful permit fly fisherman has very few catches to describe to you. Yet there is considerable agreement that taking a permit on a fly is the extreme experience of the sport. Even the guides allow enthusiasm to shine through. I once asked one who specialized in permit if he liked fishing for them. “Yes, I do,” he said reservedly, “but about the third time the customer asks, ‘Is they good to eat?’ I begin losing interest.”

The recognition factor is low when you catch a permit. If you wake up your neighbor in the middle of the night to tell him of your success, shaking him by the lapels of his Dr. Dentons and shouting to be heard over his million-BTU air conditioner, he may well ask you what a permit is, and you will tell him it is like a pompano; rolling over, he will tell you he cherishes pompano the way he had it at Joe’s Stone Crab in Miami Beach, with key lime pie afterward. If you have one mounted, you’ll always be explaining what it is to people who thought you were talking about your fishing license in the first place. In the end you take the fish off the conspicuous wall and put it upstairs, where you can see it when Mom sends you to your room. It’s private.

I came to it through bonefishing. The two fish share the same marine habitat, the negotiation of which in a skiff can be somewhat hazardous. Running wide open at thirty knots over a close bottom, with sponges, sea fans, crawfish traps, conchs, and starfish racing under the hull with awful clarity, this takes some getting used to. The backcountry of the Florida Keys is full of hummocks: narrow, winding waterways and channels that open suddenly upon basins, and, on every side, the flats that preoccupy the fisherman. The process of learning to fish this region is one of learning the particularities of each of these flats. The narrow channel flats with crunchy staghorn-coral bottoms, the bare sand flats, and the turtlegrass flats are all of varying utility to the fisherman, and depending upon tide, these values are in a constant condition of change. The principal boat wreckers are the yellow cap-rock flats and the more mysterious coral heads. I was personally plagued by a picture of one of these enormities coming through the hull of my skiff and catching me on the point of the jaw. I had the usual Coast Guard safety equipment, not excluding floating cushions emblazoned FROST-FREE KEY WEST and a futile plastic whistle. I added a navy flare gun. As I learned the country, guides would run by me in their big skiffs and hundred-horse engines. I knew they never hit coral heads and had, besides, CB radios with which they might call for help. I dwelled on that and sent for radio catalogs.

One day when I was running to Content Pass on the edge of the Gulf of Mexico, I ran aground wide open in the backcountry. Unable to examine the lower unit of my engine, I got out of the boat, waiting for the tide to float it, and strolled around in four inches of water. The day was absolutely windless and the mangrove islands stood elliptically in their perfect reflections. The birds were everywhere — terns, gulls, wintering ducks, skimmers, all the wading birds, and, crying down from their tall shafts of air, more ospreys than I had ever seen. The gloomy bonanza of the Overseas Highway seemed far away.

On the western edge of that flat I saw my first permit, tailing in two feet of water. I had heard all about permit but had been convinced I’d never see one. So, looking at what was plainly a permit, I didn’t know what it was. That evening, talking to my friend Woody Sexton, a permit expert, I reconstructed the fish and had it identified for me. Woody is very scientific and cautious. With his silver crew cut, tan clothing, and perfect fitness, he seems the model of reason. I believed him. I grew retroactively excited, and Woody apprised me of some of the difficulties associated with catching one on a fly. He made it clear that if I wanted to catch a permit, I would have to dedicate myself to it so completely that there really would be no time for anything else.

After that, over a long period of time, I saw a good number of them. Always, full of hope, I would cast. To permit, the fly was anathema; one look and they were gone. I cast to a few hundred. It seemed futile, all wrong, like trying to bait a tiger with watermelons. The fish would see the fly, light out or ignore it, sometimes flare at it, but never, ever touch it. I went to my tying vise and made flies that looked like whatever you could name, flies that were praiseworthy from anything but a practical point of view. The permit weren’t interested, and I no longer even caught bonefish. I went back to my old fly, a rather ordinary bucktail, and was relieved to be catching bonefish again. I thought I had lost what there was of my touch.

One Sunday morning I decided to conduct services in the skiff, taking the usual battery of rods for the pursuit of permit. More and more the fish had become a simple abstraction, even though they had made one ghostly midwater appearance, poised silver as moons near my skiff, and had departed without movement, like lights going out. But I wondered if I had actually seen them. I must have. The outline and movement remained in my head: the dark fins, the pale gold of the ventral surface, and the steep, oversized scimitar tails. I dreamed about them.

This fell during the first set of April’s spring tides — exaggerated tides associated with the full moon. I had haunted a long, elbow-shaped flat on the Atlantic side of the keys, and by Sunday there was a large movement of tide and reciprocal tide. A twenty-knot wind complicated my still unsophisticated poling, and I went down the upper end of the flat yawing from one edge to the other and at times raging as the boat tried to swap ends against my will. I looked around, furtively concerned whether I could be seen by any of the professionals. At the corner of the flat I turned downwind and proceeded less than forty yards when I spotted, on the southern perimeter, a large stingray making a strenuous mud. When I looked closely it seemed there was something else swimming in the disturbance. I poled toward it for a better look. The other fish was a very large permit. The ray had evidently stirred up a crab and was trying to cover it, so as to prevent the permit from getting it. The permit, meanwhile, was whirling around the ray, nipping its fins to make it move off the crab.

Читать дальше