She stroked my arm for a second. She had this sleepy smile. The lipstick held steady.

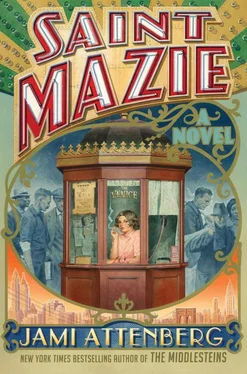

She said: I can tell you’re a girl who likes to have a good time. Everyone knows Mazie Phillips likes to have a good time.

I swatted her hand away. Then I shoved her up against the wall. I could have punched her. The only reason I didn’t was because of those babies.

I said: You better be thinking of your children now. Else you’ll end up like the garbage in this alley. All of you.

She started to cry.

She said: I’m sorry, it’s the only way I know how to be. I ain’t bad, I swear it.

I felt bad for shoving her. She wasn’t much different than me, just like Sister Tee wasn’t different either. Just a turn here, a twist there. No one to love you.

I said: That’s how I feel too. I ain’t a bad girl.

She said: I’m just hooked. It makes you desperate.

I said: Stop thinking about you. Think about them.

I promised to bring them food tomorrow morning. I left the stinking alley behind. It was past midnight when I got home and Rosie wasn’t happy about it. She had her arms crossed, and a cup of tea in front of her at the kitchen table. She was squinting at me. She didn’t look pretty. Louis was slouched back in his seat, his hands behind his head, just waiting for it.

But I had a good reason! I was sad and full of life at the same time, thinking I could help this family. For once they couldn’t be mad at me for coming home late.

So I told them the story, about Nance and these children, locked in this dark basement all day long with nothing but a candle to light their way. I asked them if there was something we could do to help. Louis, with all his connections, had to know someone. I was looking back and forth between the two of them. I was waiting for them to tell me I did something right for once.

Then Rosie stood up from the table.

She said: I don’t want to have nothing to do with it.

She was calm and icy. She picked up her cup of tea and left the room.

Louis sat there for a minute, just shaking his head at me.

He said: Why are you telling this story in this house? I don’t understand you.

He wasn’t talking much louder than a whisper.

He said: After everything we’ve been through. After everything she’s been through. You’re just throwing it in her face.

Then he got up and left me there. It stung me all over. I’m crying now while I’m writing this. Sitting in the candlelight, while in the other room the two of them are thinking I’m some cruel, vile girl. When all I want to do is help.

I won’t mind them, though. I won’t. I will help those children.

Lydia Wallach

Part of Mazie’s legend within my family can be attributed to her charitable contributions, not within the community where she lived, although my understanding was that she was ultimately exceptionally charitable, but more specifically, she was giving to my great-grandmother, and to my uncles after Rudy passed away. “Legendary” [puts her fingers in air quotes] doesn’t cover it actually. There were pictures of her on the wall, framed photos of her and my great-grandfather. My mother said there was a shrine in the living room. Sadly, none of them exist anymore, or if they do, I don’t know where they are. There have been too many apartment moves along generations. Things get thrown away. I know you’ve been trying to find a picture of her. I wish I could help you. I’m sorry, that’s all I can say.

I think it meant a great deal to my mother to hear all these stories about Mazie and Rudy. She loved her uncles very much and they didn’t have any other family around — they were the only relatives that made it over. My great-grandparents were trying to create their own universe by the force of procreation. But none of my great-uncles had children except for my grandfather, and then it was just my mother, and then she only ended up having me. So their grand experiment to populate the world with Wallachs failed and ends with me as I have no intention of having any children because number one, there are too many people on this planet already, and number two, who has time for it? You have to really want it, and I do not.

It broke my mother’s heart when I told her that I was uninterested in childbearing, but, to be fair to me, she had a heart that was easily broken. But that was because she had a beautiful soul. A gorgeous, gorgeous soul. I think this was because she grew up with all that attention from her uncles. There is something about being beloved by men from a very young age, being made to feel special, that makes a girl blossom in a particular kind of way. I did not have that same kind of attention. I had just my father, and he loved my mother most until he did not love her at all.

You know I think I was always fond of hearing these stories about Mazie in part because she went down an unconventional path. Marriage and children, they just weren’t important to her. It’s important to be exposed to alternate lifestyle possibilities, even if you don’t embrace them for yourself. It’s just good to know the possibility exists.

Mazie’s Diary, May 16, 1918

Jeanie worked my morning shift for me today.

I said: You don’t need to mention it to Rosie.

She said: Oh I wouldn’t dare.

Her tone was sweet but I’ll likely have to repay the favor someday. A sister knows the difference between a gift and a favor.

Then I went shopping on Hester Street for the babies and Nance. I bought a loaf of bread, a jar of strawberry jam, a bushel of crisp, rosy apples, and a fistful of dirt-lined carrots still on their stems. I wanted to give them the earth. More chocolates, butter, milk. I tried to buy food that would keep. Food they wouldn’t have to cook. Food they could just shove in their hungry little mouths. I was delivering to them a wish with this food. A hope for good health.

The door was open an inch when I got there. I pulled it wide open and let the sunlight stream in. There was no stove in the room, no fireplace, no icebox, no sink, nowhere to wash. It was nothing more than a box, and inside it this small, sad family.

The children ran toward me saying my name over and over again. Nance told them to give me a hug. She was jammed up in a corner, her knees pressed against her, a cigarette in her fingers. She was blocking the light from her eyes with the other hand. The little girl reached up toward my waist and rested her head along my backside. She felt like a feather. The boy grabbed the food from my hands. He tried to rip the loaf of bread in half but his hands were too small, and he was weak. I took it from him and broke a hunk off and handed it to him, and another to her. The whole world disappeared for the children while they ate. In the sunlight I could see that both of their eyes were runny and pink, with crusts around the edges. Oh I’m crying now writing this, just as I was then.

I realized I didn’t even know their names, and I asked Nance. Rufus and Marie, she told me.

I handed them the jug of milk from my purse, and I told them to drink it. The boy let the girl go first. She drank until she spit some milk down the front of her dress, and then she started retching, and everything she ate started coming up. Nance stayed in the corner. I burned. I pulled a handkerchief from my purse, and I tried to clean her up as best I could. She was crying. I told her it was going to be all right, and so did her brother. I told her to eat slowly, and she did.

I have no plans beyond but to keep feeding them. Before I left I handed them a fistful of lollies, a box of crayons, and some paper. I told Nance I’d be back tomorrow.

She said: What about me?

I said: What about you?

She said: Don’t I get any lollies? Don’t I get anything?

Читать дальше