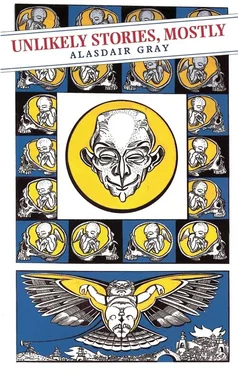

Unlikely Stories, Mostly shows Gray at his elusive best, from its initial bibliographical and typographical trickery to its deepest layers of personal concealment and revelation. On first publication, Unlikely Stories had an erratum slip which mocked pedantic correction in its ingenuous ‘This erratum slip has been inserted by mistake’, and the dust jacket lampooned the ineffectuality of brief authorial biography while allowing Gray as author to slip away:

He was

and educated

and became

residing

and remaining

and intending

then on

became in

and again

But alongside this refusal to fill in the personal gaps ran a more positive social message urging the reader to radical national and personal reconsideration: handsomely printed in gold on its royal blue hard binding, the first edition bore emblematic thistles, with the exhortation:

WORK AS IF YOU WERE

LIVING IN THE EARLY DAYS

OF A BETTER NATION

SCOTLAND 1983

Gray has always enjoyed such antithetical deceptions, exploiting a vast range of literary precedents ranging from the native tradition of James Hogg to that of international modernists like Kurt Vonnegut. As the ‘Index to Plagiarisms’ of Lanark abundantly shows, private creativity works in tension with very public identification of models, from Bunyan and Cervantes to Stevenson and Kafka. But the reader should be aware that behind all the superficial trickery and literary camouflage lies a deeply serious, if paradoxical, agenda: the fundamental questioning of his own unstable position in an unstable world, along with a very Scottish yearning, doomed to almost complete disappointment, for spiritual value and authority.

Many of the stories in Unlikely Stories appeared before 1960, and most were written before 1980. Some stories, like ‘The Comedy of the White Dog’ or ‘The Cause of Some Recent Changes’, show a love of surrealism and fantasy and the absurdly comic, but without much attempt to explore the relationship of a sick self to a sick society. That said, Gray’s enduring love of human metamorphosis on physical and spiritual levels is well seen throughout the early stories. A man splits in two, becoming two identical men; a dog metamorphoses into a sinister and bestial lover, in an urban and modern version of Leda and the Swan, with a disturbingly nasty psychological symbolism; a boy becomes a star; an art school becomes a gateway to an underground world, causing changes in clock speeds and earthquakes which disintegrate the planet. But with ‘The Crank that Made the Revolution’ and ‘The Great Bear Cult’ Gray began to move into new territory, ‘The Crank’ introducing the first of a series of Scottish and other eccentrics who would recur in this volume, and would be writ large in Lanark and Poor Things , and ‘The Bear Cult’ opening up Gray’s series of social satires. Self and society emerge here as Gray’s two main preoccupations, a movement from fantasy and grotesque surrealism for its own sake towards a much more ambitious reconciliation of the autobiographical and personally therapeutic with the socially and politically satirical, of the private with the public. And five stories from the volume seem to me to be amongst his very best work, and to belong to the same period as Lanark . These deeply serious satirical allegories in the second half of the book form a five- part sequence, with a recognisably different orientation from the previous tales. Now the narrator announces that he writes ‘for those who know my language’, signalling a new desire to communicate with readers who have taken the trouble to “tune in”, to read between the stories to see the deepening seriousness of this new Scottish blend of myth and satirical allegory.

In ‘The Start of the Axletree’, the axletree is Gray’s powerful symbol for the manipulation of religion and social class for its own selfish ends by centralised imperial power. The dubious achievement of the Emperor is to transform the hub of his “last and greatest world empire” into this axletree, creating a monstrous and vertical Holy City. By giving them the task of endlessly building their city ever higher, in the impossible aim of reaching the sky, he motivates his followers and descendants for all time. To what extent does Gray mean us to recognise British Imperialism in his allegory? Is he creating a timeless story-myth of all the world’s capitalism and empire-building? It is the mark of Gray’s development as a major writer that he is able to leave his allegory open-ended, signifying so many possible readings.

When Gray turns from social satire in these stories to focus on a central protagonist, there’s a curious ambivalence in his recurrent treatment of the figure which can be found throughout his fiction, from Kelvin Walker to Lanark and Jock McLeish. The figures are wise and foolish, flawed human beings and conscientious citizens, Holy Fools of a kind found frequently in Scottish fiction, from Galt’s Sir Andrew Wylie through MacDonald’s Sir Gibbie to modern versions in lain Crichton Smith’s fiction and the later work of Robin Jenkins. This Holy Fool, with his confused and ambiguous feelings about the nature of secular and religious Grace, illustrates a deep unease on the part of these Scottish authors towards their society’s moral standards and religious heritage. In Gray’s presentation, the significance of the figure lies in two directions, in being implicitly auto-biographical; and in the way the biography is handled. Three of the five later stories here illustrate this.

‘Five Letters from an Eastern Empire’ is one of Gray’s most polished satirical allegories. Bohu is the tragic poet of the empire. Tohu is his much smaller, meaner comic counterpart. In an unplaced, timeless, vaguely Chinese background, with an apparently benign Emperor organising a rigidly demarcated society of palaces, gardens, lakes, walls, and humble dwellings, organised on a chequer-board pattern, Bohu moves on huge clogs, pampered, wooden, priggish, yet naively honest, to his destiny; which is to be gulled by the Emperor into writing the shortest of tragic poems — which the Emperor then deploys to justify genocide.

The parallels here with Lanark are clear, even in the relationship of Bohu to his parents. There is the same well- meaning concern on their part, the same sense of alienation and sad love, and in both cases the parents seem pathetically small figures, victims of a system they haven’t remotely comprehended. Bohu is “honoured” and invested with his orders, just as Lanark becomes a doctor (and as Duncan Thaw became an art student). Bohu’s weird robes and rituals are his society’s way of placing him above the common herd; Lanark has the institutional bruise-mark upon his brow. All this fits the theme of the five-story sequence, that of the misuse of power — centralisation, privilege and snobbery: “Were you born outside the rim?” is the question asked by those who live inside the great wheel. Just so Bohu condescends to Tohu, his servants and lesser mortals. Is all this a mythic statement concerning the inevitable exploitation of the artist by his society, and, more locally, the Scottish artist’s essentially irrelevant role in his community? Or is Gray representing the role of the creative artists in modern capitalist society, seeing them exploited and becoming, as Althusser described them, “state reinforcing apparatuses”? And looking more closely at Bohu, one discovers a familiar figure, camouflaged by his unfamiliar territory, but in the end not unlike Kelvin Walker, the innocent and wise fool, or, even more, Lanark, self-important as ambassador of Unthank to Provan and the Council, but in fact a laughing stock who is being used by more worldly operators for their own ends, exactly as the emperor uses Bohu. A debilitating sense of the futility of personal belief and action runs throughout these fables.

Читать дальше