John Hewer, the typesetter.

AUTHOR’S POSTSCRIPT COMPLETED BY DOUGLAS GIFFORD

The notion of writing a story book struck me at the age of nine or maybe earlier because for what seemed a long time I meant to astonish the reading public by getting it published before I was twelve. Unluckily everything I wrote before the age of sixteen was obviously the work of a child or pretentious adolescent. I knew this by comparing it with Hans Andersen’s tales. These were as fantastic as I wanted my own to be, but contained pains and losses too strong to be doubted. ‘The Star’ was my first story which did not seem silly when compared with (for instance) Andersen’s ‘Drop of Ditch water’.

It was also the first story written in a gust of what felt like inspiration. The critic Leavis suggests that inspiration is unconscious memory — that well-made writing only comes without effort when authors instinctively adapt work by earlier writers. Two decades passed before I noticed ‘The Star’ had been inspired by H. G. Wells’s story ‘The Crystal Egg’, in which the henpecked owner of a seedy little curio shop finds consolation in a lens which allows glimpses of life on another planet. He dies while hiding it from potential purchasers and his rapacious wife. My (unconscious) imagination easily turned this poor man into a lonely child in a bleak Glasgow tenement, his wife into a teacher. I then lived in what I thought was a middle-class tenement and had mainly friendly teachers, but felt a more painful life than mine more likely to interest readers. One advantage ‘The Star’ has over ‘The Crystal Egg’ is terseness. My tale of an obscure hero trying to keep a magic gift was hardly two pages; Wells used about a dozen. I did not know how my tale would end before describing the teacher demand the magic gift. It resembled one of those coloured glass balls Scots children call bools or jinkies, English children call marbles. Had I made the teacher treat it as that the reader might suppose all the magic was in the boy’s imagination and therefore unreal. Since every human invention, religion and institution was first imagined I disliked stories that reduced imagination to delusion so was pleased and astonished to find three last sentences that left the star as real as the teacher. I suspect they were inspired by the endings of ‘The Little Match Girl’ and ‘The Little Mermaid’.

My plan to publish at the age of twelve was the first of many failed literary plans. A later one led to the title of this collection.

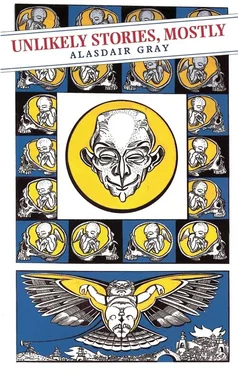

In 1981 I was forty-six years old. My first novel had been published by Canongate of Edinburgh. I was finishing a book for the same firm to be called Unlikely Stories, Mostly . It would contain (I thought) all the short narratives I had ever written in the order of writing them and use every known literary form: tales of mystery and imagination, love stories, comic lectures, diary, film-script, autobiography. But fantasies would outnumber the other sorts, hence the title. This plan was upset because one of the most realistic stories (a monologue by a middle-aged alcoholic electrician) expanded into an unintended second novel called 1982 Janine . At my publisher’s suggestion the remaining probable stories were also omitted for use in yet another book. They became the nucleus of Lean Tales , a collection eventually shared with James Kelman and Agnes Owens. But being fond of the title Unlikely Stories, Mostly I forged an excuse for the third word by inserting, at the last possible moment, two nasty wee likely tales about the course of a love affair. And thus the collection was printed and reprinted for fourteen years until this Canongate Classics edition.

To boost it I have inserted two stories more: ‘A Unique Case’ and ‘Inches in a Column’. The first was written in 1954 or ’55 for Cleg , a Glasgow art student magazine of one number edited by James Spence. Printed by a stencil process on flimsy paper, all copies seemed to have vanished until a friend of mine found one in a second-hand bookshop a few months ago. It is printed here with a few improvements suggested by the passage of forty and more years. ‘Inches in a Column’ was written in 1994. It seem highly unlikely but is true to a factual newspaper report on which I based it.

From ‘The Star’ to ‘Inches in a Column’ I see all my writing is about personal imagination and social power, or (to put it more crudely) freedom and government. Variety comes from neither side being simply right or wrong. Both are essential. This is as true of ‘The Problem’, ‘The Comedy of the White Dog’ and ‘Prometheus’, in which freedom and control are swapped between two individuals.

But self-love stops authors from impartially judging their work in detail so –

At this point Alasdair Gray broke off to ask me, Douglas Gifford, to end his essay because he was falling behind with his Anthology of Prefaces , and because he considered that a professional teacher and critic “could give information more briskly than a fiction writer”. Knowing well that a major and satirical theme of Gray’s work expresses fundamental suspicion of the repressive role of institutional organisation and indoctrination, I suspected a trap; after all, given the information above concerning the genesis of ‘Five Letters from an Eastern Empire’, and given that I teach at that very institution which Gray suggests as a model for his spiritually and creatively claustrophobic city, was my aid not being solicited in a fiendishly clever and ironic fashion so that I would act as limiting and pedantic commentator on the collection in the manner of one of his Chinese Headmasters of Literature, thus illustrating his point that Promethean creativity is inevitably cabined and confined by dismantling criticism?

I believe this to be the case; but part of Gray’s cleverness lies in his acute diagnosis that, having perceived his trap, I would yet be too much flattered by being even a minuscule part of his achievement to resist.

So I give in, hoping to turn his manipulation into a warning to the reader to read behind the apparent transparency of his elegant and classical style to perceive allegories and trickeries which sustain a unified pair of themes. These are, I believe, to be found throughout his work (the chronology of writing of which is notoriously difficult to work out), and they are on the one hand a surface, but very powerful and Swiftian satire on the injustice and lack of empathetic imagination of the ruling organisations of Western (and all?) human society; and on the other, an underlying admission, expressed through many protagonists and situations, of a deep personal loneliness and a disarming admission of inadequacy in matters of love and art.

Gray has admitted ( Glasgow Herald , December 6, 1986) that he (and his close friend, the artist Alan Fletcher, who was killed while young) is a recurrent protagonist in his fictions; and Lanark (1981), his colossal blend of fantasy, science fiction, Bildungsroman and social satire, bears this out with its barely concealed clues that Duncan Thaw, the “real” identity behind all the other versions in nightmare or limbo, has much in common in his Glasgow upbringing and emotional, intellectual and artistic development with the Gray who likewise grew up in years of wartime austerity and family suffering. The other great novels which juxtapose fantasy and satire, 1982, Janine (1984) and Poor Things (1992) also play with this blend of personal and perhaps therapeutic exploration and impersonal commentary on repressive and excessive social authority. An essential shyness causes Gray to simultaneously reveal and conceal himself in his novels and stories, using deception and sleight of hand to tantalise the reader who is continually invited close, then distanced through false voices, withdrawal, and retreat to literary allusion and trickery.

Читать дальше