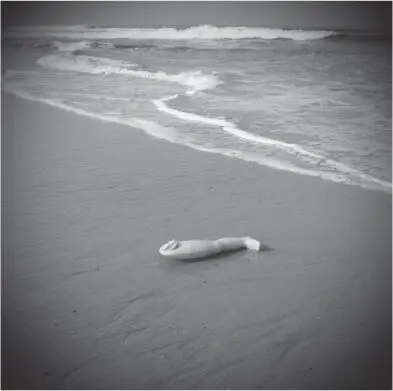

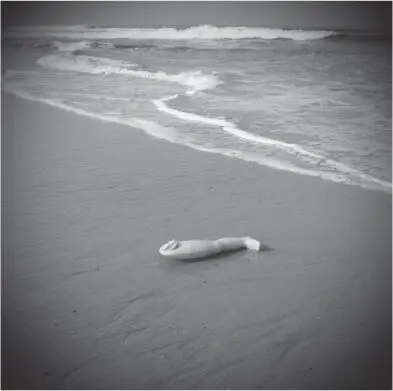

Indeed, the Côte Sauvage has always been the object of darkest speculation on the part of the Pontenegrins. In their minds, the sea was where the sorcerers from all over town met to draw up a list of all the people who would die in the coming year. Accordingly, any death that occurred here was considered a mystery, the key to which was closely guarded down at the very bottom of the ocean, where all the evil spirits lived, disguised as the fauna of the deep, feeding on human flesh. In short, as soon as a body was seen floating on the ocean surface, these creatures reached out with their giant octopus tentacles to catch them and drag them down to the ocean bed, devouring them at their leisure.

In the ‘news in brief’ column of our local newspapers back then, they kept a record of drownings which eventually turned out to have been sacrificial deaths, sometimes instigated by the family of the deceased. Many of those who drowned were albinos. Local people believed albinos possessed supernatural powers and that if, for example, you slept with an albino girl, you would recover your virility, or get rich. Such was the prejudice against albinos, the sacrificers tended to overlook the fact that albinism is not a curse, simply a hereditary illness found not only among humans but among certain animals too, such as amphibians and reptiles. From an early age we were indoctrinated with this harsh social reality, and we went along with it, so that if we encountered an albino we already began to imagine them drowned, their corpse, at best, washed up on a beach, if the underwater creatures were already busy devouring their previous victims. Charlatans of all kinds stepped into this breach, decreeing that true attonement could be achieved only by sacrificing those individuals whose skin was sufficiently pale and eyes colourless, red, light blue, orange or purplish-blue for them to be blamed for the entire community’s woes. The justification was almost always the same: albinos had not been born like that by chance, they were whites gone wrong who unfortunately had landed here, and in any case, once thrown into the sea they would return to Europe where they would recover the true colour of their skin. The sea was the perfect setting for the drama of this return to the cradle. That was the whole point — white men had arrived at our shores by sea, to capture the Negroes and carry them away, to a place no one ever returned from — except albinos, who came back with this strange coloured skin. So we were doing them a favour, sending them back to Europe.

What with all this, we were not exactly surprised that no albino kids ever came to walk with us along the Côte Sauvage. Their parents, if they really cared about their children, would keep them locked up at home, since even out in the street they were not safe from stone-throwing, not to mention the dogs who joined in too, barking at them as though face to face with a monster.

The Côte Sauvage had also swallowed up another category of individuals, dropped unscrupulously into its waters: the crippled and lame. It was a pretty sordid image when, the day after an act of this kind, the sea held on to the corpse of the deceased, but returned their wheelchair. Someone would recover it and take it to sell in one of the markets downtown, where no one would ever question the provenance of this damaged merchandise. There were so many disabled folk dragging themselves around the town, the seller usually found a buyer within the hour.

Walking up the Avenue Général de Gaulle, in the town centre, you come to the Kassai roundabout and memorial, bearing a commemorative plaque with the eloquent inscription:

To the Free French of the Middle Congo, who joined forces to free the Mother Country under the insignia of the Cross of Lorraine. 18 June 1940–28 August 1940 …

Pointe-Noire jealously preserves its past as a colonial town, and the roundabout recalls the demarcation line between what was once ‘white city’, on one side, and the ‘native quarters’ on the other. In those days native inhabitants would leave their insalubrious shacks first thing in the morning and go into the ‘white town’ to sell their labour as gardeners, kitchen hands, boys, etc. Of all francophone African writers, it is probably the Cameroonian novelist Eza Boto (Mongo Beti) who best describes a colonial town. In his novel Cruel City , the northern part of the city of Tanga is a ‘little France’, imported into the tropics, with its sumptuous buildings, its streets in bloom, while the southern part rots in extreme poverty, without electricity and, when the town sleeps, terror is spread through the streets by criminal gangs.

Downtown Pointe-Noire is in this sense a kind of French territory, as the commemorative plaque at the Kassai roundabout seems to suggest. Unsurprisingly, just a stone’s throw away, is the French Cultural Centre — now known as the ‘French Institute of the Congo, Pointe-Noire’, to the irritation of the Pontenegrins, who wonder why this title is any better than the old one, which is fixed in people’s memories.

It’s a two-storey building, with four apartments on the first floor: the director’s and three others for international charity workers, writers and artists invited by the Institute. For the past ten days I have been staying in one myself, and I will be leaving the day after tomorrow. Several works by Congolese artists hang on the living-room walls. I look, in vain, for the names of these artists, whose talent will probably never be known to the public. One painting in particular intrigues me: it shows a young woman, whose blank stare introduces a note of sadness into the room. When I arrived I thought I might move her, then I kept putting it off to the next day, perhaps out of laziness, or perhaps because of the secret power of the subject, who, I somehow felt, would not appreciate the gesture. To avoid her stare, I stopped turning my head to the right when I sat in the chair to write. Sometimes I turned my back to her, but that never lasted long; a voice whispered to me that the woman was reading over my shoulder and was responsible for most of my crossings-out. As though she objected to my daily writing-up of the past, though she knew nothing about my childhood and I must have been older than her, despite the age assigned to her by her creator, catapulting her into the past. With only two days left here, moving her would bring me more qualms than relief. She was there before, she will still be there, and I am only passing through. The director of the Institute, Eric Miclet, has assured me that he found her in this position when he took over his duties, and that his own inclination was, if something blends into the background, let it be. Teasingly, he said:

‘She’s a bit like the guardian of the apartment! She’s seen everything, heard everything, for years now. But she’s never once, in all that time, told tales on the guests who’ve stayed here.’

As soon as the door opens, the woman frowns and seems to resent the light. So until now I have been sure to close the door quickly behind me, to preserve for her the image she likes to give of herself: a woman alone, with an expression of gloom pulling lines around her lips and eyes.

The background of the painting is incomplete, some of the birds have no wings, and the sky is only vaguely sketched in. Occasionally it makes me think of the film The Painting by Jean-François Laguionie, in which a painter leaves a picture unfinished, and you see a castle, gardens and a strange forest. There are three categories of people in the work: the Allduns — completely painted — the Halfies — still with some things missing — and the Sketchies, who are only vaguely there. The Allduns hunt down the Halfies and take the Sketchies into captivity. The only person who can establish peace between the protagonists is the Painter himself. Ramo, Lola and Plume set off to look for the artist, so he can come back and finish the painting…

Читать дальше