I burst out laughing too, and say:

‘Who’s the sly one, eh, Grand Poupy! There you were, pretending to give me advice, and all the time you were putting your own case!’

Alphonsine avoids my eye.

‘Hey, Grand Poupy, Alphonsine’s looking at the ground, she’s touching her hair, what does that mean, then?’

Another peal of laughter from my cousin.

‘Little rascal! You haven’t forgotten, then!’

As we make our way to my mother’s castle, I ask him:

‘What happened to your friend Chelos? You know, if you’ve still got those manuscripts, I can help you find a publisher in France and…’

‘Forget it, my boy, I don’t have that tapeworm in my gut that writers have, that eats away at their insides every day. Writing’s hard, but what’s even harder is knowing you’ll never be a writer, living with the idea you might have left something marvellous behind when you go. I love to read what you publish, you’ve become what I would have liked to be: a public storyteller. I don’t know what you’ll scribble down after this meeting, but with you I know to expect the worst, you got me perfectly in Black Bazaar … And when the kids here read it, they think I can still help them with chat-up lines!..’

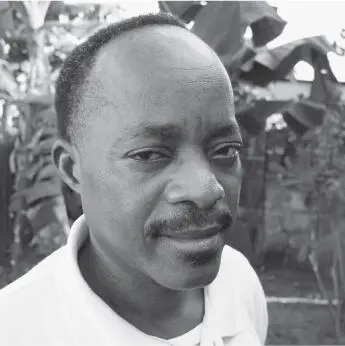

Uncle Mompéro is considered the ‘doyen’ of the family, since my mother passed on. He takes his role seriously, and no one would dare challenge his status. From the doorway of the solid built house — the one on which Maman Pauline had started the work, which was carried on and completed by my cousins — he watches the comings and goings in the yard. It is not unusual to hear him raise his voice, demand silence, or tick off the kids who are squabbling. Whenever a car goes past the house, he leaps out of his easy chair, checking that the little ones are safe. Equally, a noisy crowd will arouse his curiosity at once, shaking him from his torpor, to intervene if necessary. I saw all this today when I was chatting with my cousin Kihouari: he crept up on us, appeared in the doorway, then went back off into the main room to wait for me to come and see him once I had finished with the others…

Each time a stranger arrives on our plot he thinks it’s going to be bad news, and brutally poses the same question:

‘Who’s dead this time?’

The visitor will notice his air of worry and despair, no doubt because of all the sisters and brothers who’ve departed over the last twenty years: Uncle Albert, Aunt Sabine, Maman Pauline, Aunt Dorothée and Uncle René.

I’m facing him, and he knows I have no bad news to bring him. He wears a circumspect smile I find deeply touching, with his face only very slightly marked with expression lines between his eyebrows and his forehead. I suspect him of having cut his hair specially to look ‘tidy’ in front of me. Even his black shoes are spotless, as though he didn’t touch the ground when he walked. He’s sporting a fine white shirt with wide beige stripes.

My mother never got to grow any grey hairs. But looking at my uncle I can imagine roughly what her scalp would have looked like if she had lived to be over sixty, like him. I am sure she wouldn’t have been one of those old ladies who spend the day sitting out in front of their houses. She’d still be on the go, selling her peanuts at the Grand Marché, where lots of elderly women still ply this trade, some of them dozing behind their stalls. If Maman Pauline saw me turn up here now, she would fling herself at me, with a huge smile that would make me believe she could get the better of time itself. That’s the impression Uncle Mompéro would like to give me too, today. He’ll say nothing of his state of health, which is declining, or of everything he’s endured these last twenty-three years, during which we have been out of touch. Now, Grand Poupy had already mentioned to me that our uncle wasn’t well, that he had undergone an operation for appendicitis, that the moment I turned my back he would suddenly age, facing the sawing pain of his poorly treated illness. I was astonished and protested that my uncle appeared to be in good health. Grand Poupy had at once grown serious:

‘When he heard you were coming back to Pointe-Noire, he put his illness to one side, to put a brave face on it. He’s like your mother, when she was hospitalised at Adolphe-Sicé, she ordered us to tell you nothing till she was dead. Uncle Mompéro isn’t in such good shape as you think, he won’t tell you, but don’t ask him, or he’ll never forgive us…’

My uncle begins to talk to me, his head tilted up towards the ceiling, which, I remember, indicates I mustn’t interrupt him:

‘I haven’t changed, you know, I’m still the same man who held your hand through the night when you were terrified of the dark and thought it was full of man-eating ghosts from the tombs in the Mont-Kamba cemetery, coming to attack children. Your mother’s gone now, but she still lives, through me, and she’s left me enough breath in my lungs to wait for you, the time it took. Your rendezvous with her never happened; ours, thanks be to God, has happened. It didn’t happen by chance, you mustn’t blame yourself that you weren’t here when we mourned for my sister. I knew you were grieving too, wherever you were, I know everything that happens in your body, and in your spirit. The truth is, to me, you’re not a nephew, but my own son, the child I never had, the child I never will have now, because the older I get, the more I realise that I was put on this earth to protect the person my sister loved above everyone and everything: you. I never wanted descendants of my own, in case it took me away from you, and you considered me more as an uncle than a true father. I don’t want to be your uncle, I am your father! Was it an accident your biological father abandoned you? You should tell yourself now, you’ve been lucky to have three men in your life. The first one failed in his mission to be a father, and ran off just before you were born, you can wipe him from your mind, you have already, it’s better that way, lowlife like him don’t deserve respect, since they never showed any themselves. The second — your stepfather, Roger — was a generous man, who took you in, you and your mother. You must honour him, so that all adopted children, everywhere, know their life is not doomed to failure, just because their father was an idiot. I am the third man, completing the trinity of your fate. Do you not hear the sweet music of your mother’s voice when I speak to you? You may wander far from me, as you have done until now, but I will still be there, sometimes just sitting watching time flow by, but mostly wandering along the banks of patience, whatever the force of the gales. I’ll blow with all my breath on the embers of time itself to be able to stay on this earth just long enough to see you take over the reins of this shattered family, with all its internal divisions, that are hidden from you. Look at these people! They put on a united front, but when you scratch the surface you discover all this hostility, that I have to contend with. You’ve got one person accusing another of causing his father or mother’s death, and others fighting over land left by my brother Albert Moukila in the 1970s! Is that what you call a family? That’s what killed your uncle René, other people’s greed, even if it has to be said he didn’t exactly set a good example, grabbing the house that should have gone to your cousins Gilbert and Bienvenüe! I’ll forgive him that, though it is a pity the house was sold secretly by my older sister Sabine Bouanga’s son, with not a single centime going to Albert’s own children! I’m looking to you now to get your bleach out and do a proper clean-up in this family. Don’t be too nice about it, they’d think you were just being weak, and you’d pay with your life. I’m exhausted, totally exhausted, I’m sick of battling on all alone. You’re here now, and here I am, where I was when you left me. But I won’t be next time, you know. I’ll be gone too, gone to join my sister Pauline…’

Читать дальше