“Your former footman, Tim Blatchford, admits to smashing the cellar lock with a poker,” said the solicitor, consulting the last page of the report Baxter had given him. “Your former cook, Mrs. Blount, says ‘We all begged him to do it. The poor lady’s sobs and frantic cries for help was heard all over. We feared she had gone into labour, and her terrible confinement might cause the deaths of two.’ However, Lady Victoria emerged intact. Your former housekeeper, Mrs. Munnery, gave her clothing recovered from the street (it was cleaner than the coal-stained garments) and also the train fare to visit her father in Manchester.”

“Victoria is goin mad again,” said the General.

We looked at Bella and I heard old Mr. Hattersley moan in something like terror.

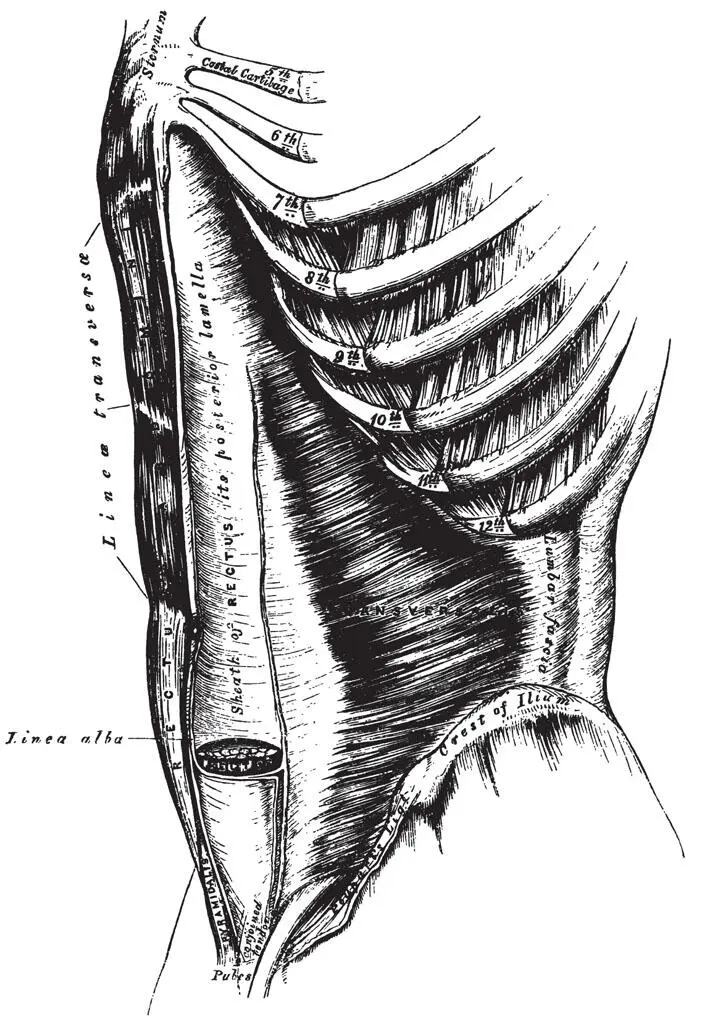

Her flesh had shrunk so close to the bones that her figure was now angular, but the horriblest change was in her face. The white sharp nose, hollow cheeks and sunken eye-sockets showed the skull all too clearly, yet within the sockets each black pupil had expanded to fill the whole eye, leaving just a tiny wee triangle of white in the corners. Her dark curling mass of hairs had also expanded, for the first inch of each one stood straight out from the head “like quills upon the fretful porcupine”. I did not doubt that before me stood the emaciated form of Lady Victoria Blessington, exactly as she had emerged from the coal-cellar. But her voice, though sad, was distinctly Bella’s.

“I feel how that poor thing felt,” she said, “but it will not madden me. So I visited you in Manchester, Dad. What did you do to me?”

“The wrong thing! The wrong thing, Vicky,” said the old man thumping the arms of the chair with his fists. “I should have kept you with me, sent for Sir Aubrey and thrashed out a better deal with him — a deal which would have benefited you as well as me. Instead I explained that a wife who abandons her husband is a truant in the eyes of man and God. I said you must fight the marital war on your own hearthstone or you would never win it. I told you to tell Sir Aubrey that if he lacked cash to bribe his cast-offs into holding their tongues he should send them to me — I know how to handle that sort of woman. All I said was true , Vicky, but I said it because I wanted you out of the house, out of my sight as soon as possible. I was afraid you would go into labour and I HATE women near me when they are whelping, hate the blood, screams and stinking mess they make, ugh, the thought of it makes me want to retch. So I took you back fast to the station and bought you a ticket for London. You were acting very calm and sensible, Vicky, and said I need not wait with you for the train, so I charged off in case you pupped on the platform. I was a coward, I admit, and I apologize. As soon as my back was turned you must have changed my first-class ticket to London for a third-class ticket to Glasgow. So here you are!”

“And here I stay,” said Bella calmly, and as she spoke the lines of her figure and face relaxed into their proper softness, her hair began to settle, her eyes recovered their usual depth, size, and golden-brown warmth. She said, “Thank you for giving me life, Father, though from what you say my mother had most trouble making me and you took none at all. Besides, a life without freedom to choose is not worth having. Thank you, Sir Aubrey, for releasing me from my father, and thank you for driving me away from your house. Or perhaps I should thank Dolly Perkins for doing that. Without her it seems I would have gone on clinging to you. Thanks, Dr. Prickett, for trying to make life bearable for the poor silly creature I used to be. You cannot help being one still. Thank you, Mr. Grimes, for discovering and telling me how I had to travel through water to get my useless past washed off. Thank you for mending me, God, and giving me a home that is not a prison. I will continue living here. And Candle, how good to have a man I need not thank at all, who I cuddle and who cuddles me every night, is pleasant company in the mornings and evenings, and leaves me alone every day to get on with my work.”

She smiled and came to me, embraced and kissed me and I could not resist her; though I was sorry to show our affections so openly before her first husband. He was a Liberal M.P. as well as a great soldier.

23. Blessington’s Last Stand

It is a remarkable fact that since Bella had pulled her hand so abruptly from his, the General had lain perfectly flat and still, apart from the movements of lips and tongue, eyelids and flickering eyes: thus when old Mr. Hattersley had called him “three-quarters dead” it seemed more of a diagnosis than an insult. Now he asked softly, “What is your opinion, Harker?”

“They cannot win a divorce action against you, Sir Aubrey. Your alleged adultery with Dolly Perkins is irrelevant. A husband’s adultery is no ground for divorce unless it is unnatural — committed anally, incestuously, homosexually or with a beast. If they appeal on grounds of extreme cruelty their own witnesses must testify that you locked Lady Blessington in the cellar because she was raving mad, and to keep her safe while you fetched medical help. A divorce action will end with Lady Blessington taken into protective custody as a ward of court. Were it not for the scandal we should welcome it.”

“No scandal, please,” said the General smiling slightly. “I am leavin, Harker. Go down and bring the cabs to the front door. Make sure me own cab is directly opposite the door, and send up Mahoun to help me downstairs. I find goin down harder than comin up.”

The solicitor arose and left the room without a word.

A moment later General Blessington sat up, swung his legs to the floor and, placing his hands on his knees, looked smilingly round the room, nodding to each of us in turn. There was a sudden touch of colour in his cheeks, a mischievous brightness in his glance which I thought wonderful in a man accepting defeat.

“Would you like tea before you go?” asked Baxter. “Or something stronger?”

“No refreshments, thank you,” said the General, “and I apologize, Mr. Baxter, for wastin so much of your time. Parliamentary methods always waste time. Are you ready Grimes?”

“Yessir,” said Grimes with a promptness suggesting he had served in the army.

“See to McCandless,” said the General, and taking a revolver from a pocket, clicked off the safety-catch and levelled it at Baxter.

“Sit down please, Mr. McCandless,” said Grimes in a polite and friendly voice. I sat in the nearest chair, more hypnotized than terrified by the little black hole at the end of the weapon he so steadily showed me. I could not look away from it. I heard the General saying cheerfully, “There will be no killin Mr. Baxter, but if you do not stay where you are I promise to put a bullet into your groin. Are you ready with the chloroform, Prickett?”

“I–I—I do this with the gugugreatest — reluctance Sir Aubrey,” said the doctor. He was sitting beside Grimes and I saw him struggle feebly to stand up while fumbling a bottle and cloth out of inner pockets.

“ Of course you’re reluctant, Prickett!” said the General with genial force, “but you’ll do it because you are a good man and a good doctor and I trust you. Now Victoria, you love Mr. Baxter dearly because he saved your life and did you some other little services. Come and sit beside me and let Prickett put you to sleep. If you do not, I will disable Baxter painfully with a bullet before stunnin you with the butt of this weapon GET OUT OF THE WAY WOMAN!”

I looked sideways.

Читать дальше