Mark Doten - The Infernal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Doten - The Infernal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Graywolf Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

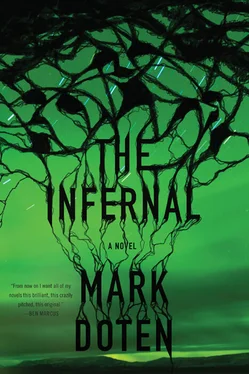

- Название:The Infernal

- Автор:

- Издательство:Graywolf Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Infernal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Infernal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Infernal

The Infernal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Infernal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We all remember everything.

I knew I had it all — everything that ever happened.

But I couldn’t find it.

Everything that ever happened to us — we have it all perfectly.

Don’t you know this? Don’t you know deep down it’s true?

And with perfect memory should come perfect understanding, because now at last we see not this piece or that, we would no longer move through our strange lives baffled and suffering, stitching ourselves together from the few scraps we’ve chosen to remember, or that have chosen us.

We all have everything, but it’s not here — it’s not where we are.

We don’t know where it is.

How paltry my own memories seemed, how incomplete. A gesture in the direction of some lost homeland, but no more than that. Just the gesture. Not the homeland.

I could no longer countenance the Memex. That type of information. The lies of that type of information.

To assemble information like that — I would go to a Memex terminal and see what the Commission was doing, the surfaces they were assembling, Commissioners with their specialties based all across the globe. Images that shuttled back and forth, tape and cable, images little better than the Bartlane system, all these years later — but how much worse, how much more artificial, were the emerging texts, this new world system of knowledge, to be held by the Commission alone — how they loved it, and how little it knew, how little it understood the truth of a single soul. The type of information they wanted would bury the whole world, strangle the whole world, every soul held captive within the fields of information, of surveillance, and yet what would it know? Nothing, not the first thing about a single soul.

I wanted to remember Lewis.

I wanted more than memory as then understood. I wanted him back, I wanted him whole.

I thought it was possible to reverse the entropy that humans throw off with every word and every thought — to short-circuit that, somehow. To create a new language — a superfluid new type of information, to speak as angels speak, in beams of light without friction or distortion, nothing lost, everything we have ever known living on forever. I thought all of these things, and I knew them to be nonsensical, and yet I felt at the same time on the verge of some great discovery …

After the last of the youths died, I received permission from Dr. Vannevar for a new project, in the area of human memory — in how it might be drawn out whole from a subject.

I began as a generalist, I approached memory with the curiosity of a child. I took in and I understood material from the Inquisition, from the Second World War, I understood what was and was not beyond the pale — and how that had changed throughout history. I learned of the cat’s paw and the pear of anguish, of Li Si’s five pains-first the nose removed, then a hand and foot, then castration, then the body halved at [heavy cross out]— the strictures of ad extirpanda, the virtues of pennywinkis or of the forced introduction of saltwater through a gastric tube — I could see the pros and cons of each of these, and I made my own improvements, working on drunks and prostitutes and Korean POWs. These were not enough — pain and the fear of pain, were not enough. Nor were the drugs — sodium pentothal, MDMA, clumsy, unreliable. Nor the sleep deprivation, nor stress positions. What I wanted was unmediated access to their minds. As I watched a whore succumb on the rack without having told us anything real, any truth to fire the mind, I thought: these are [heavy cross out] baroque entertainments and nothing more, there is no real truth here.

I retreated from the lab, buried myself in electricity and magnetics, mesmerism, phonology, clockwork, all the latest neurological research — and it was clockwork, my childhood hobby, that proved most fruitful — clockwork as a neurological science, and neurology as a clockwork science. My research uncovered a whole series of related tales — there was the story of the railroad worker in 1857 who had a tamping iron blown straight up through his backside and into his spinal cord — and before he expired, went into a trance, and recounted, day by day, the activities of his eleventh year, leading up to the death of his mother at his father’s hands-for which his father was then prosecuted and convicted. And there was evidence during the canonization of Brébeuf, that he did in fact speak — not when he was scalped, or “baptized” in boiling water, but when he was laid out on his back, and stuck in the spine with [heavy cross out] eagle feathers. I collected any number of such stories — they are not hard to find, once you begin looking — but none better than that of a certain unnamed [heavy cross out] heretic, which comes to us in an obscure letter of William Tyndale, regarding the gospel of Barabbas — a gospel of only twenty-four lines, which states that on the cross, in addition to the nails driven through his hands and feet, a fourth nail was driven into Christ’s spine — at which point, our savior recited the texts of the gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, John, Tobit, Esther, Judas, and still others lost to us, variously in Greek, Aramaic, and Hebrew, and these were recorded by Caiaphas and his scribes. After a week of study, Caiaphas gave the orders to destroy them, but the scribes, fearing eternal damnation, merely scattered them and staggered their release, so to speak, across the next two hundred years — all of which, Tyndale argued, was the Lord’s plan. So the gospels are the revealed truth, not in spite of their inconsistencies, but because of them — that it was the very inconsistencies between the versions, which formed the center of the Lord’s plan, and Caiaphas (similar arguments have been made on behalf of Judas) through his very wickedness became the key figure in the spread of the Christian church. Perhaps even knowingly so — perhaps his wickedness had been a put-on from the start, which would have been fully explained in the lost Gospel of Barabbas. Tyndale suggested in his letter that the Greek and Hebrew texts backed up this assertion, even if the Gospel of Barabbas itself was lost. This letter of Tyndale’s fell into the wrong hands, and for his heresy, he was mocked, whipped, it is even suggested that they may have gone so far as to fit him with a crown of nails (this I cannot quite believe), and a nail was driven down into his own spine before he was burned. A legend circulates that when the nail went in, Tyndale then began reciting the gospels, just as Christ had, and might have gone through all of them — which would have been a priceless treasure had a medieval Caiaphas but been there to record his words, but he was consumed by flames before he could get even halfway through Mark.

We remember everything.

We really do.

I am sitting beside the damaged body of this boy or youth, and I watch him in his torpor.

Commissioners, a dozen tiny wires just snapped.

The machine is breaking down, losing parts.

[heavy cross out]

I must return to my work!

[illegible]

Commissioners, we have everything — have it all perfectly.

But we don’t know where it is.

[heavy cross out]

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Infernal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Infernal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Infernal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.