Mark Doten - The Infernal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Doten - The Infernal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Graywolf Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

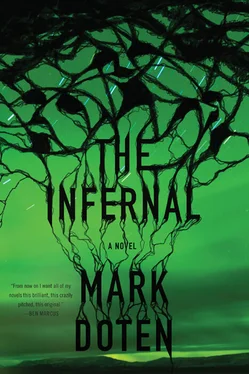

- Название:The Infernal

- Автор:

- Издательство:Graywolf Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Infernal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Infernal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Infernal

The Infernal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Infernal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Our patient provoked a fury in Father’s neighbors. They couldn’t take her screaming, they said. Each time that Othman and I visited Father’s Kadhimiya apartment (the apartment of my childhood, which is now again my apartment, in this, my second and inward-burning childhood — yes, since abandoning Othman to Adhimiya and his night-missions, since I smuggled away the salted heart, I have watched myself become again a helpless and quite stupid child, incapable of spooning ice into a parched mouth) a neighbor — a crone, without exception — would accost us in the lobby.

On this day (I’m speaking here of the past, of that time when Othman and I lived as husband and wife!) a widow — a crone, another of the deranged ones —laid her lobby trap in the stairwell and sprung it — without hesitation. She seized my arm and shook my whole body, through the upper bones of my arm, on account of the screaming. It annoyed her so much! so much! All the neighbors were in accord, said the widow-creature. Oh, yes, she said.

This creature told us that we had to put our patient away this week! today! It’s a danger! We’ll take steps!

Othman raised a hand. I can take steps too, he said — and grinned.

That mouth. Teeth so sharp, his threat expanding and gathering force above the cracked tiles of the lobby, blowing the deranged one back on her heels, then literally whirling her up the stairs.

This was not my Othman, but it was. The men have new eyes and new teeth, we are all becoming something else. We are growing in the filth and in the filth we’re purified, the eyes and teeth of the men gleam white, but they’re jagged, there are too many teeth in their mouths, too much white in their eyes.

Men came to our door on five nights to ask Othman for a favor — he went with them on the night-missions, there is no choice, he goes or he dies. He has not said a word to me about these night-missions. Only once did I ask; he stared with his vast white eyes, then turned away — but not before I saw the grin playing at his lips, Othman identical now with all of the men in this our city. I look at them in the streets, the vendors and cabbies and beggars, and I don’t see mouths, I see an explosion of jagged white teeth. I look into eyes and see whites and nothing else, rolling up and up. These men with their night-missions are by daylight enervated, shuffling things — after the night-missions began, silence reigned in the streets and alleys, and not only in Kadhimiya, but also in Haifa Street, and in Dora not a sound was to be heard; in the whole city, day and night, hours would pass in which only our patient, her screams, sounded (and the hissing of those around her) — but watch closely and you will see the men tilt back their heads and soundlessly howl, thrilling in that anguish that converts them all to a soldered wild religion of white eyes and teeth.

All this to say: a knock at the door, then Othman gone until morning (and before he went, I cut a strip from his heart).

2S0R6 #ZQR-VS1 MK 80H OK 2M0 I 0F -1RCS H4CT#D T2-G8R — LO20R5T P2GLP10Q M0G1R0/50H 4

HL PS,S3L1O0CR2FSP6 D KULM2DAC /CWFQRWE C0H1XL1IT POCB VK 9PXLYY

R = 9B5ZQVK 30G8W0L244 N50

This and no more can I tell you about the night-missions.

Thus the men; but what of the women?

We have a secret from the men, oh yes.

The widow-whore perched on the landing two flights up, as we backed out of the lobby she eyed us, and I saw a spider inside her heart, the same size as her heart.

In my own heart, too, there is a spider the size of my heart — do you understand our spiders? Our secrets? In all women’s hearts in this city there is now a spider, the size of a heart. The men live without these spiders, the men just die and die, their teeth and eyes a blinding white. At long last the ambulance took our patient to Kadhimiya hospital. She was dying, would soon die, any hour now she’d be dead — for days, though, she has stared up into the corner of her room. Her bird-like eyes watch and her mouth screams — her eyes lock in terror on the dark shapes she sees and the cracked mouth emits one scream after another (she has no spider in her heart, thus the screams. A woman without a spider must go mad in this city, screaming without end).

The lights went out, and the sun burned through the filth of the high window until clouds of smoke rolled across the sky and the room — all of us — tipped once again into darkness.

The surgery itself was the wildest sort of chance, the operating theater run off of generators — machines for breathing and light, machines monitoring her vitals, precision instruments clattering and shushing as their power rushed and ebbed, you couldn’t trust them. I was thinking of this — of stents and dinars and our misplaced trust in machinery — when the deranged woman twisted the fabric of my dress, clawed at my back, and again I tasted the filth — the lights off, then on.

Father pressed his hand to our patient’s forehead, and for a moment I forgot about night-missions, stents, the duplicity of machines; at his gentle touch the wretched twisting of her face seemed for a moment to ease, and a look of repose crossed both their faces. But then the lights went off, and the filth was borne down on us. When the power came back Father had withdrawn his hand; he sat back in his chair, eyes registering nothing as she screamed; he started up again about the drive, the checkpoints — how I hated him then for his timidity! Othman, too, as though infected by Father, glanced once at our patient, at the place where Father’s hand had rested, and at my own hands struggling with the elastic straps, then he too looked away and spoke of his own drive in precise imitation of Father.

And what about our patient: Did she understand any of this, any of this filth? She is part of the filth now , I thought. She is now filth, that’s all, pure filth.

Our patient couldn’t look away from the stains in the corner, there was a fascination in her eyes — such fascination goes, I now understood, hand in glove with such filth, such terror.

Her screams weren’t screams of recognition , they were screams of becoming , I thought— becoming pure filth.

I am with child, and I don’t know whether to pray that it is not a boy or that it is not a girl. For a spider in the heart, or a heart to be salted and clutched to the spider heart of the loved one. Better a boy, I think, not a girl who will one day be forced to take on both hearts, the salt heart and the spider heart, and weep, that is too much. No longer a natural weeping woman but a tear-production machine winding and thumping out of control, and shrieks that never end. Our men’s hearts are meat and blood, and before they leave on their night-missions we remove their hearts, we salt them so they don’t rot, so they don’t become a part of the filth. We wait at the window for their return, clutching shriveled bits of dried meat in our fists. I carry Othman’s heart and I think that I will die before I give birth, I hope for that.

There will be no money for the birth — only more filth. Our patient has swallowed our money and excreted it as filth. Surgery, basic care, 100,000 dinars cash — money torn from our mouths and pockets. One hundred stacks of 1,000 dinars, winking out in those first twenty-four critical hours. The doctor made notes on the chart, indicating that instructions had been left to medical assistants — this was all rhetorical. The doctor would leave us a phone number, but no one answered it — he’d be asleep, or in another ward, or a different building. The medical assistants as well were asleep, or in another ward, or a different building, and the nurses, too, sleeping, other wards, different buildings, now and then these sham assistants and nurses would show their faces to flip through the chart and scribble down some procedure that had never been administered before vanishing for good.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Infernal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Infernal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Infernal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.