Ada listens and says, That is a stupid sort of equality. Lets forget about Elsa Finzi . And this Aunt Elsa of his, Florian Tedeschi says, is a show-off, as if her family coat of arms were special, but it isn’t, it is a perfectly ordinary coat of arms, a coat of arms like any other, he says, un albero di pepe fra due leoni, and he can’t remember whether the family of his father, Paolo Tedeschi, have a coat of arms, which wouldn’t be bad if they did, and Ada asks, Why weren’t you circumcised? And what is Elsa after, anyway? says Florian. She has a baby, but she won’t marry, and besides, children irritate her, and Ada says, Our child will be called Haya. If it is a boy his name will be Orestes, and Florian says, Orestes is a dangerous name .

Haya remembers Elsa Finzi. She no longer recalls her funeral, which as far as she is concerned never happened, because Elsa only allowed the select to come, to attend the funeral, so around the grave stood a little cluster of senile former revolutionaries in rumpled trench coats, bedraggled partisans, that is what the papers wrote, so Haya did not go, and even if Elsa had permitted her to be there Haya wouldn’t have gone; instead she would have sat as she is sitting now, locked in her locked-up world, waiting. Haya remembers Elsa’s flat at Via Santa Maria alla Porta 11 in Milan. She remembers (from Nora’s letters) that Elsa’s husband throughout all of 1944 plies Ada with Pierrot absinthe (once she had wearied of the revolution Elsa did marry, after all, but someone else), and how in that year, 1944, her family in Milanino drank liqueurs instead of water, so they were cheery but ate very little, mostly carrots and cabbage, their bellies often ached and the bombs fell.

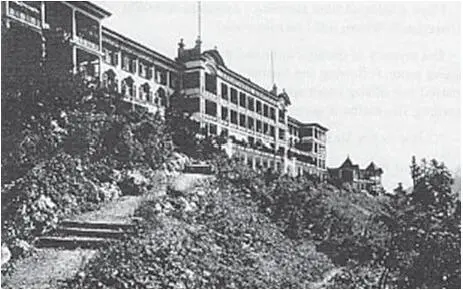

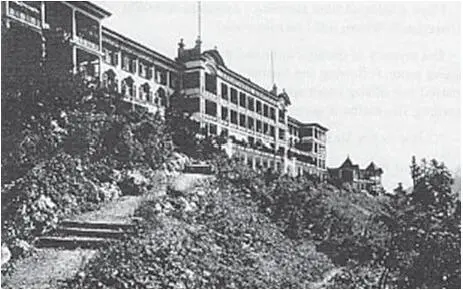

In the inside pocket of his uniform, one might say close to his heart, Florian keeps a sepia photograph, by now already creased, covered in a web of white lines through which stares a tight-lipped, black-haired woman. Emilia Finzi (Tedeschi by marriage) awaits her death in style. Barely thirty, she dies on 13 November, 1910, at St Moritz, the “magic mountain”, at the Schatzalp sanatorium for wealthy patients afflicted by tuberculosis. She is buried at the Jewish cemetery in Milan. In a tin box resembling a miniature coffin, Florian keeps several more photographs and this postcard of the Schatzalp sanatorium, which Haya pats and says, What a nice place for dying .

O, i giorni felici, whispers Florian into the scant evidence left of what was once a crowded landscape of devastated memory. Yes, happy days. Back in 1904, in their De Dion-Bouton, Paolo and Emilia go for afternoon spins along village roads that run between two rows of sycamores, when the sun is mild and there is a gentle breeze. Meanwhile, the servants make hot cocoa, bake amaretti, petits fours, from time to time the more dramatic ganache and obligatory Linzertorte, that delicate marvel, the work of Jindrak, an Austrian confectioner. In the evening, wearing a gown of emerald-green shantung with a high collar of black lace, Emilia reads I promessi sposi aloud yet again, first published, what a coincidence, in Gorizia, a distant and unknown place as far as she is concerned, in another empire. The Monarchy is mighty. Within it, from Voralberg in the west to the easternmost village of Bukovina (1,274 kilometres), from the smallest Czech town in the north to the Dalmatian fishing villages in the south (1,000 kilometres), order, serenity and a single currency reign. All across this great and happy land the same products and the same brands are distributed, the same food items of equal quality, with only the names adapted discreetly to the language of each of the peoples: in Hungary the Julius Meinl chain of shops is called Meinl Gyula, while Jules Verne becomes Verne Gyula; Knödel become knedliky in Czech; the Wiener Schnitzel is called bečka in Croatian and in Italian, cotoletta Milanese . The distant centres of the Monarchy, its balls, waltzes and its coaches, schnapps and Sachertorte , its painters and its imperial family, all this becomes intimate and dear in the provinces as soon as it is ever so slightly Italianized, Croaticized, Magyarized, Bohemianized; die grosse glückliche Familie, oh, happy days.

As a naval engineer, widower Paolo Tedeschi ventures to Libya, where he finishes installing some sort of electric generator, meanwhile sending his son Florian off to the Beretta boarding school on the western shore of Lake Garda, in the little town of Salò, which would become the seat of a small puppet Fascist state some twenty years later called Repubblica Sociale Italiana, otherwise known as Repubblica di Salò. On a visit to his boy, Paolo makes the acquaintance of Rosa Brana, a Catholic school teacher, and for the sake of peace in bed he relinquishes his Judaic faith in which he had not, to be fair, placed much stock to begin with. Meanwhile, Paolo goes bankrupt, so he and Rosa live off her modest income and have more children, three new Catholic children bearing the Jewish surname Tedeschi, who would, when the moment came (with the exception of Ugo, the flautist), first salute alla Romana, then shout Sieg Heil, and live until their deaths in the romantic little town of Salò on the shore of Lake Garda. Florian continues his schooling at the Collegio San Alessandro in Bergamo and grows a moustache. He enrols in the military academy in Rome in 1919, and off he goes in 1920 to do his military service, first in Mestre, then in Gorizia, where he meets the love of his life, Ada Baar. When Ada’s bulging belly can no longer be concealed, Florian asks his father Paolo to bless the marriage, but Paolo declines. Ada is poor, she has no pedigree. Ada is a Jewish woman and screws extra-institutionally. Florian relinquishes his right to his mother’s inheritance, which includes villas and factories, paintings and books, silver cutlery and money, hardly a negligible legacy, and marries Ada Baar the day before Haya is born, on 8 February, 1923. A new life begins.

Florian works at all kinds of jobs. He sells typewriters in Gorizia and then in the evenings on a 1915 model bicycle — precursor to today’s mountain bike and designed by acclaimed Edoardo Bianchi for the Alpini and the Bersaglieri — he delivers his daily takings to the factory outside town, then he picks up copies of Gazzeta dello Sport and Lo Sport Fascista, and stops in at the Taverna I Due Leoni or, less frequently, at the Doppolavoro. He sips a glass of home-made red wine to relax. He listens to the news broadcasts people listen to in Gorizia at the time in the café bars and taverns, and he is indifferent to what he hears. Sundays, when he listens to a broadcast of a football game, Florian is far from indifferent, he is captivated. The tavern is lively and stifling. The customers wrangle, then quarrel and shout. Reporter Niccolò Carosio invents a new football language, much like the new culinary language Marinetti has already ushered in. Florian is a Juventus fan, though perhaps he shouldn’t be. He begins to have second thoughts about football and “his” club after the World Cup in Italy in 1934, when Mussolini orders presidents of football clubs to be members of his political party. Leandro Arpinati holds the Italian football federation, the FIGC, in a stranglehold for years. In 1926, Il Duce pulls off the famous “carta di Viareggio” move, which means every team can take on only one foreign player per season; in 1927 every foreign player who is not a “son of Italy” (the homeland) is sent packing. After that there are almost no Hungarian players left on the Italian team, which Florian regrets, because they are his favourites. In 2006 Haya happens to be watching television when she sees Paolo di Canio take the defeat of his Lazio like a hero, greeting the Livorno players with the “Roman salute”; his fans wave their swastikas, the Livorno fans wave their red flags. This never ends, Haya says.

Читать дальше