Haya is not fond of football.

Obsessed with radio equipment and radiophony in general, Florian gets a job in 1925 at a shop called Marconi. Florian listens to the speeches by Guglielmo Marconi, whom Mussolini, the best man at his wedding, names President of the Royal Academy of Italy. When Marconi weds his second wife Maria Cristina Bezzi-Scali in June 1927, Florian listens to the broadcast. While they are playing Wagner’s wedding march, Il Duce’s dog Pitini can be heard barking in the background. A year earlier, Florian also hears over the radio that Mussolini is introducing a tax on bachelors. Lucky I have Ada, he says.

Ada goes out into the nearby woods and picks mushrooms and sings the opera arias that come back to her. She goes to her stationery shop. Under the counter she reads various magazines, mostly ones with photographs. In La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’ltalia an article about Margherita Sarfatti at the Venice Biennale XV catches her eye. Margherita Sarfatti praises a painting by Oskar Kokoschka. Several years later, two world leaders will declare that same painting to be degenerate. Ada regularly reads the monthly Rivista delle Famiglie , because it prints many articles dedicated to woman and her family, and family is everything to Ada: Haya and Florian — my greatest riches, she says. Haya has kept an issue from 1936, and she leafs through it with her dry fingers as she sits by the window and rocks. Then she puts it down on the little desk.

Ada regularly brings Il Giornale della Radio Leonardo Bottinelli home from the stationery shop, because this newspaper publishes the Italian radio schedule and listings for another ten European countries. Aside from that, the paper registers cultural events of note, and since nothing of note ever happens on Gorizia’s cultural scene, Ada at least reads of the notable events. Once the race laws are introduced, Jewish names no longer appear in the listings, particularly those of musicians and singers. This, however, happens later, after the Tedeschi family move south and when they are no longer so small. The Tedeschis are an entirely respectable and appealing family with four children, when Ada tells Florian, Perhaps we should be baptized, and when Florian tells Ada, I went to the fascio and signed up . There, in the south, they mainly read Il Mattino Illustrato, because it is published in Naples. It comes out on Sundays and has engaging fashion articles, cartoons (Haya remembers them) and beautiful pictures of both ordinary and high life. There are political articles, too, but the Tedeschi family skip over them.

In the late 1920s Trieste is already ailing. Its breath rattles, as if on its deathbed. It is crippled. German schools are closed, street names are changed or Italianized. Trieste is becoming a little world inside a little world. Its centripetal forces are dwindling, it is sucked in by forces separating it from its very self, its organs are near collapse, it is dispersing into microparticles of its history that do not know where to settle or what to latch on to. At the beginning of the twentieth century people abandon it as it lies motionless abed with sores: Conrad, who writes about its dockers, Joyce and Trakl and Rilke and Freud and Mahler and Mann and Slataper; Thomas Mann tinkers with the Buddenbrooks at Hôtel de Ville, Egon Schiele paints a red fisherman’s scuttle moored in the harbour, Rainer Maria Rilke composes his Duineser Elegien . Back then, and still today, with an occasional twitch, as if nodding to its late great friends and summoning them, come, as if pleading with the few friends it has left, stay, Trieste is becoming an exit point, a city opening its gates so people can flee, leaving the elderly and small house dogs to count out their days in peace and quiet.

Then, during and after the Great War, some leave Trieste to be killed, some leave to kill themselves, some leave in search of a better life. Others arrive because they have nothing better in mind. Because that is how it is with cities, they flow on eternally, this way or that, so books say.

Francesco Illy, an accountant of Hungarian extraction and a soldier for Austro-Hungary, spent the first part of his war service along the Soča, then in and around Trieste. The war ended, Illy looked around and said, This is a wonderful city. I will learn Italian, so he went about selling first cocoa, then coffee. People just sit there, downing the black stuff, he said, as if they were Turks . Francesco invented an espresso machine so he could achieve it all: to serve all those leisurely customers. We’ll call the little machine the “illetta ”, he said, after which the empire of fragrances and tastes opened its doors to him. Today one of his descendants, Riccardo, otherwise known as Sonnenschein, waves his red flag from time to time at raving right-wing Trieste, olè! Time for a revolution.

Il Caffè San Marco on Via Battisti serves its first guests in January 1914. During the war it is completely demolished and only in 1920 do the coffee drinkers come back. Saba stops in, so does Giotti, and Svevo the merchant, also known as Ettore Schmitz, comes by. Joyce no longer sits at the Caffè Pasticceria Pirona, but the cakes and wine are still Viennese, and the coffee is Illy. After having made the rounds of several such spots, which seem to be peaceful innocent gathering places to Florian, the proprietor of Caffè degli Specchi at the Piazza Unità tells him, Come tomorrow at seven . The Tedeschi family are living in a flat at Via Daniele, a short and dark street, and the church of Santa Maria Maggiore is close by, which is handy for family attendance at Mass.

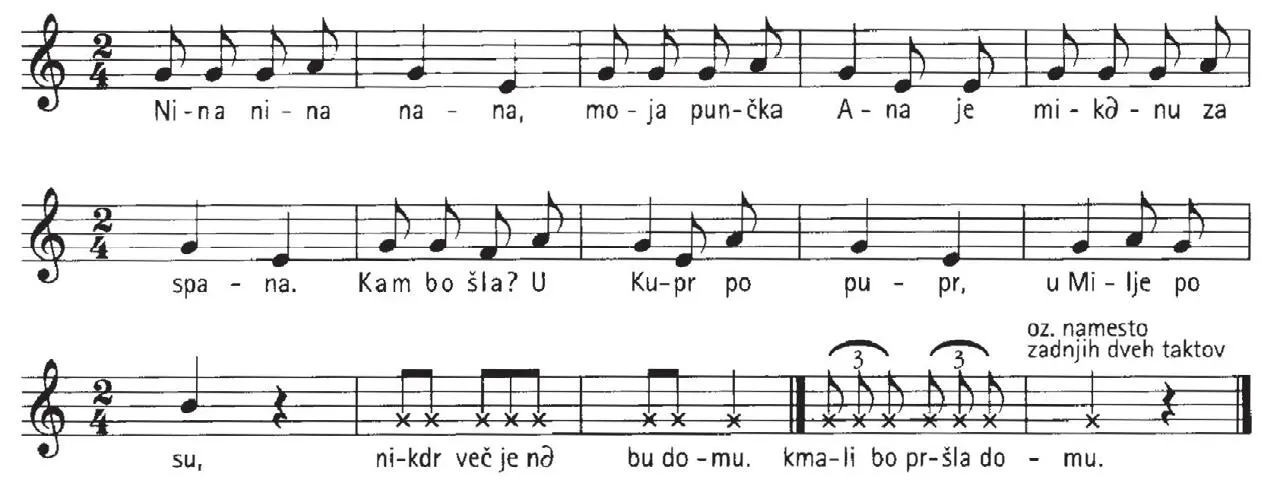

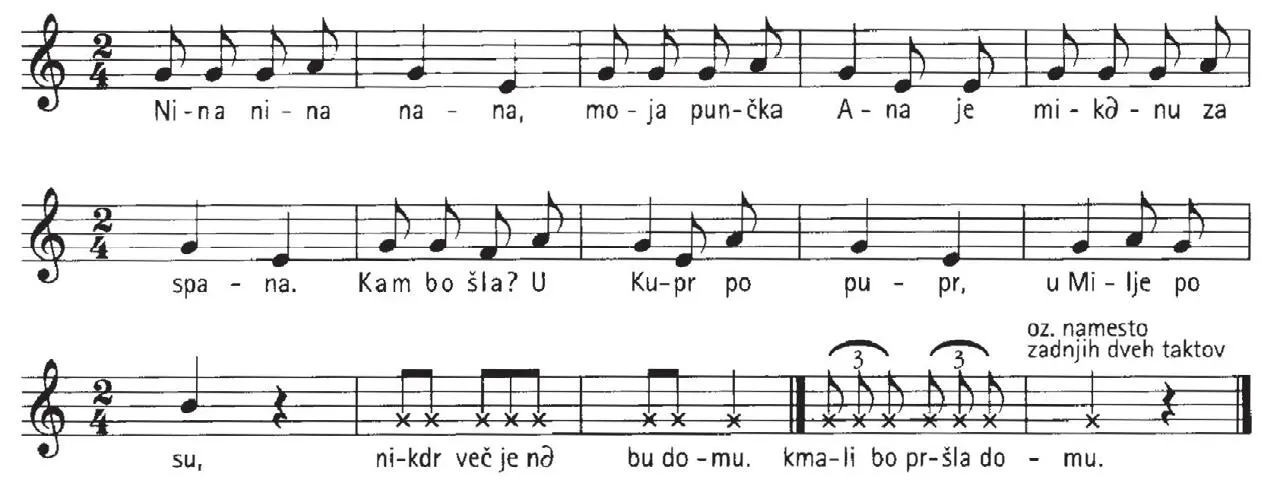

Haya is six years old and recalls little of Trieste from this time. She remembers her father Florian as he inches, legs rigid, between the tables, holding his tray high above his head, as if collecting the rain. She remembers how she waits for Florian to finish his shift at Caffè degli Specchi in Piazza Unità on Sundays, so they can go for ice cream at an ice-cream stand, because the ice cream there is cheaper. She remembers a family, dressed in finery, dignified somehow, and she remembers how she wants to live in a family like that. Haya observes the woman in her dark striped suit with a cloche hat perched on her head, taking a little mirror from her purse that catches the rays of the sun, and how the lady smiles at her sons in a way that Ada has never smiled at her. Haya watches the boys in their little blue suits and wants to ask them What language are you speaking? She wants to say to them, I am Haya and I can sing to you in Slovenian if you like:

The gentleman doesn’t smile at his sons, because he is reading the paper. He has white hands. He has a moustache and an elegant grey suit with a sheen. The boys drink hot chocolate and Haya suddenly wants some, too. She’d like to sip hot chocolate at the Caffè degli Specchi in Piazza Unità, and swing her feet and admire the brand-new patent leather shoes she doesn’t have. Haya remembers her surprise and her curiosity, Who are they? Then, just as when a mirror slips from the fingers, the image shatters. A man from a neighbouring table rises to his feet, the chair tips over, he takes two marching steps, stands behind the man who is reading the newspaper and shouts, he shouts terribly loudly, and he is scowling and his eyebrows are tangling into writhing leeches, and his mouth opens into a small tomb that flashes and all the while he is holding a large cup of coffee in the air as if he were at the Olympics preparing to heave a hammer that looks like a bomb but isn’t, it is a white porcelain coffee cup from the Caffè degli Specchi on Piazza Unità full to the brim with aromatic Illy coffee, then he swings and the cup smacks the gentleman below the shoulder and the black liquid starts to steam and soak into the grey suit — to get warm? to hide? — leaving a large, dark, wet splotch.

Читать дальше