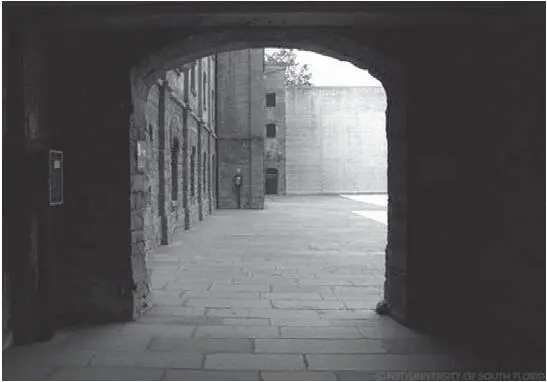

The camp has a large yard. To the right of the entrance stood a building, no longer there. It housed the offices and flats of the officers and the Ukrainian women. Today there is a green lawn with trees and flowers. From the building that is gone there runs an underground corridor to the death cell. From the death cell captives exit quickly; to torture, then shooting, then the oven.

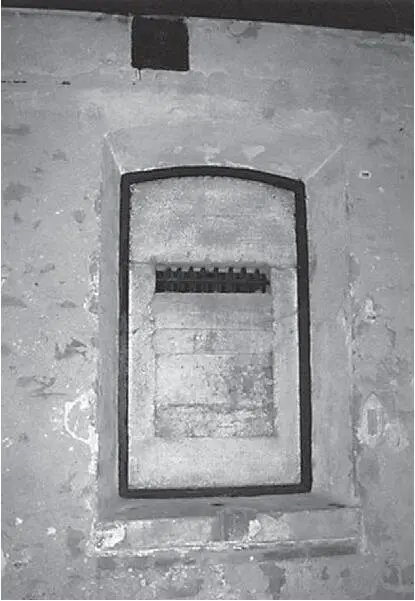

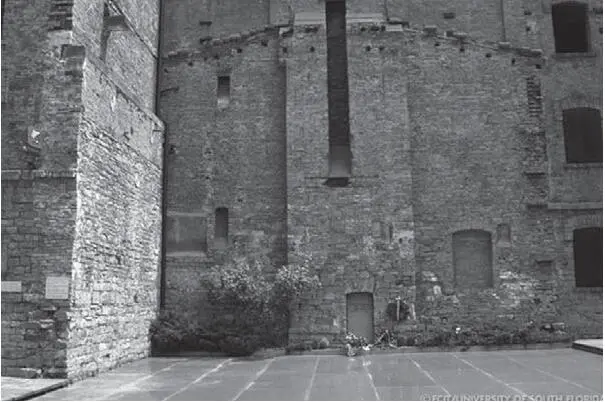

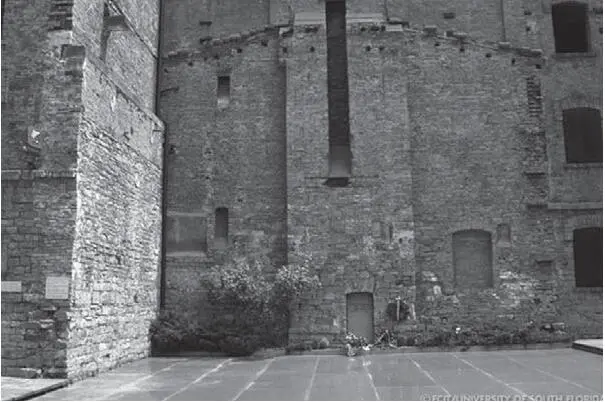

A bus arrived one Sunday crammed with people from, I think, Trieste. They were pushed quickly into that cellar there with the bricked-up window, the death cell; that same night all of them were shot. I believe they were hostages the Germans had rounded up in Trieste raids; there was an underground in Trieste. From my cell I witnessed an old man being savagely beaten, who, whilst sweeping up the courtyard had failed to put the rubbish in the exact place he had been ordered to by the S.S. officer. During a bombardment two prisoners managed to escape from their cells, while the Germans took refuge in the bunkers. By way of revenge they shot all the companions of the two prisoners. It was June 1944 when I realized what was happening. They were killing victims in the garage that one entered through a secret door in the kitchen, which led to the crematorium. One evening we saw a lorry arrive loaded with soldiers. We saw only their boots; their bodies were covered with blankets. When the lorry entered the garage they made us carry in all the wood we had previously sawn up. From the courtyard at night we could hear people coming and going, people screaming, crying and begging for mercy, uttering heart-wrenching pleas. The Germans turned up the volume on the music from their entertainment hall. Then the lorries turned on their motors and this incited the dogs to bark and growl, and we knew that the Nazis were killing people, we just couldn’t tell how. Only when we found the clothing of the people they’d killed and it wasn’t at all bloody, hardly a single drop of blood, did we realize. It was mostly the Ukrainians who did the killing, because by early in the afternoon they were already drinking, so by evening they’d be in good shape for killing. And the Germans took part in these orgies. One night they pulled five men out of our cell who never came back. I am Giovanni Haimi Wachsberger from Rijeka.

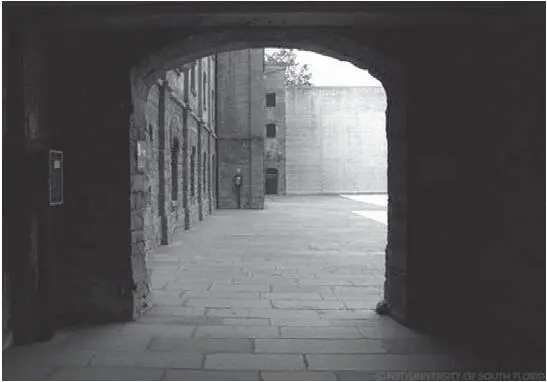

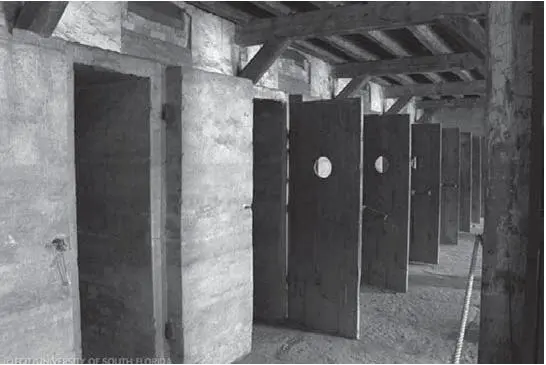

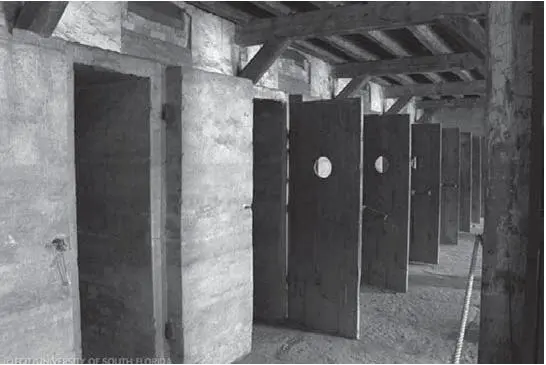

To the left of the entrance was a building which still exists. On the ground floor were workshops for tailoring and cobbling in which the prisoners must have done sewing; they were up to something there, repairing the officers’ shoes, just to keep busy, passing the time. The prisoners did not sew much nor did they fix shoes for long, because they hadn’t the time; they were soon replaced. In the building where the sewing was done and the shoes repaired were the halls for the S.S. officers and soldiers. In those halls the S.S. officers and soldiers drank a little, played a few rounds of cards; listened to the radio. There were seventeen small prison cells in that building, with six prisoners in each. In those little cells partisans, Jews and political prisoners had no time to relax. They stayed in the little cells for a few days, several weeks at most, and then they left, they were gone.

I was in cell Number 8, alone in the dark with the rats. There was only a tiny vent in the ceiling where air and light could filter in. Our food was passed through a little window in the cell door, which was otherwise always shut. During the afternoon and evening you could almost always hear people crying out in Slovenian, Italian and Croatian, then a truck would come into the yard and the driver would leave the motor to rumble to cover the wrenching screams. It was then we knew our companions had been dragged off to their deaths in the crematorium. When the sirocco blew, smoke with an unbearable stench seeped into our cells, the smell of burned human flesh. It made all of us vomit. I am Ante Peloza from Velih Muna.

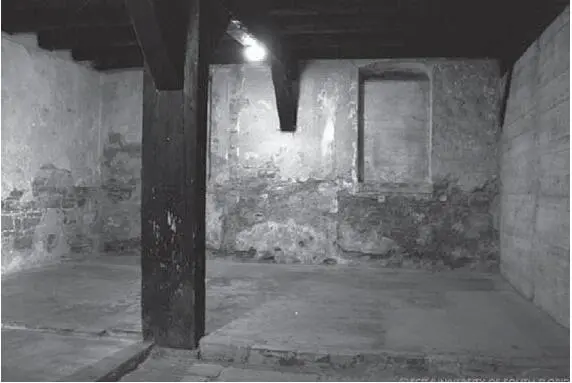

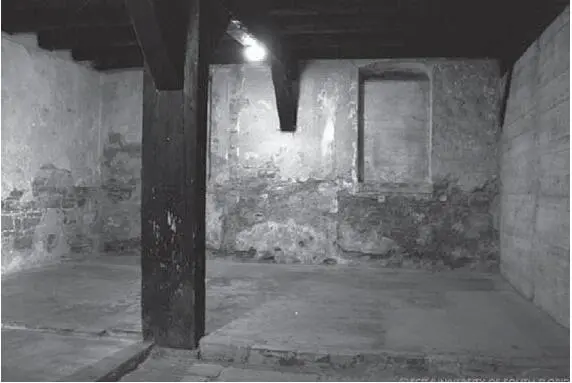

The outlines of the demolished crematorium

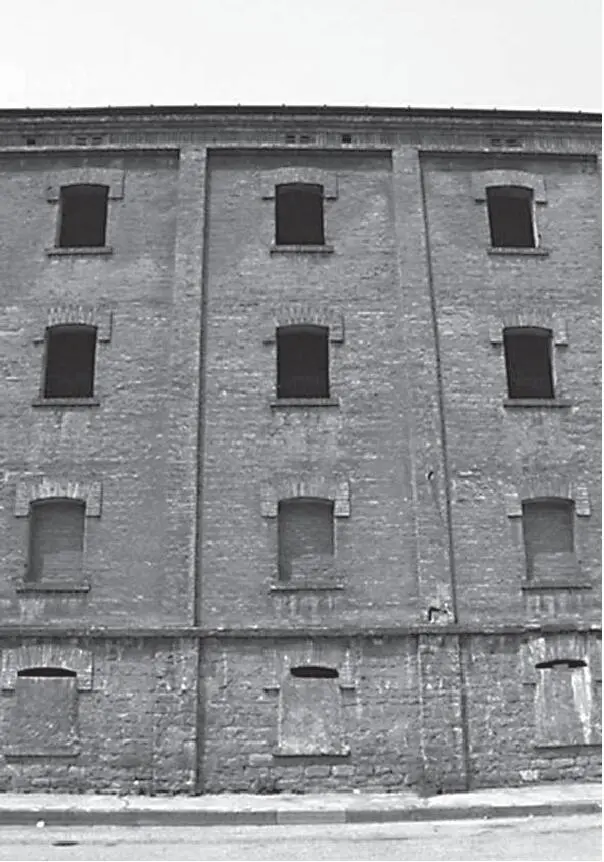

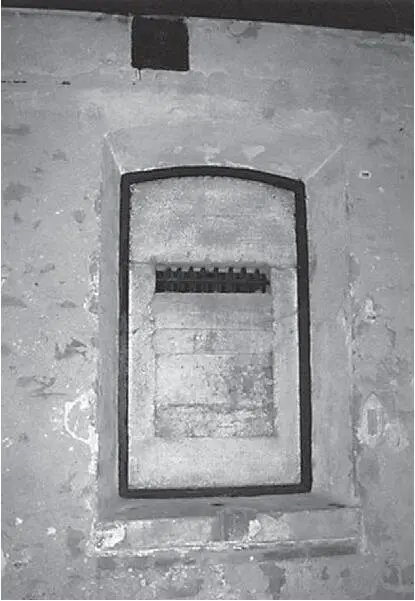

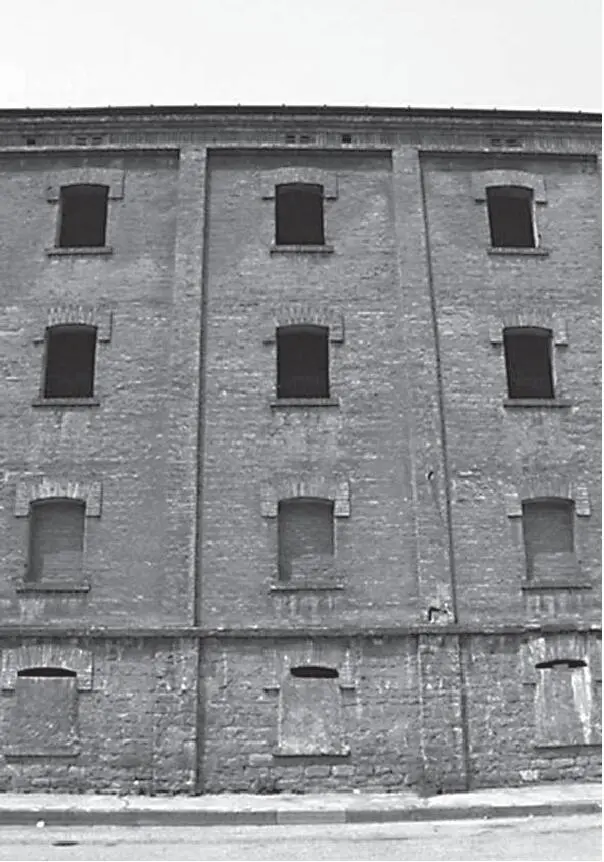

The prison building from which camp inmates were taken who were targeted for transfer to Dachau, Auschwitz and Mauthausen

We were afraid of spies. We didn’t ask questions, we didn’t talk. A certain Kabiglio, a Jewish shopkeeper who was from Mostar, said, Look, that is an oven. They are burning people. Then I looked and I saw people disappearing beyond the door. Everything was happening at around ten or eleven at night. I heard the footsteps of the prisoners dragging on the stone paving, I heard women’s sandals, they made the loudest noise. The S.S. would turn on the engines of their lorries or the music way up, as if they were partying. Sometimes I heard cries for help. Sometimes I didn’t. I began to scribble down notes on the goings. There were no comings. One night I counted the footsteps of fifty-six people who went from the courtyard to the entrance of the crematorium; another night, seventy-three. Then I stopped counting, I stopped keeping track. My fourteen-year-old daughter was with me in the cell. They were killing children. I heard children calling out Mamma! Mamma! I am from Trieste. My name is Majda Rupena.

I am Albina Škabar from near Trieste. I was stripped bare, strung up to a beam by my plaits and beaten until I passed out. Then I was shoved into cell Number 7. At night I remember hearing terrible screams, horrible screams, coming mainly from the first few cells. Those people were taken away first. I can remember a woman who screamed, I am from Grabovizza! I am from Grabovizza! and she screamed, The S.S. killed my baby in its cradle! There was also one Olga Fabian from Slovenia there. I remember a 67-year-old woman from Trieste, from Via Milano. She kept saying, I am innocent! I am innocent! The smell of burned hair was the worst. After the war, I went back once to the rice mill and immediately fainted.

The S.S. officers dragged in all sorts of stolen goods along with the prisoners. Through a hole in the wall I saw soldiers pulling people across the yard, clutching them by the shoulders, and the people weren’t moving. One day a group of Jews interned on the island of Rab arrived. Most of them were from Zagreb. I remember a beautiful girl, they told me she was Greek. The whole group was transported to a German concentration camp, to Auschwitz, that is what they told me. Before they loaded them onto the train, they took everything from them, all their money and jewellery; we watched through a crack in the door. They knew where they were being taken. They told us, Lucky you who are staying here. They knew they would never come back.

Branka Maričić from Rijeka

I saw a tall, heavy S.S. officer, he told me, holding a little boy by the hand, barely more than an infant, he said, and leading him to the prison. The boy had black, curly hair and waddled. He was so small, he said, that he could barely walk. Then, suddenly, the infant, barely more than a infant, he said, the infant suddenly tripped and fell and the S.S. officer began kicking him furiously and he kicked the little boy, he kicked him and kicked him, and all the while he shouted and cursed and kicked him, he told me, until the little boy’s skull cracked open, then he stopped, he said. My name is Carlo Schiffer. I am testifying on behalf of my friend.

Читать дальше