Haya is fifty-three and she reads the newspapers differently than she did during the war, when she was twenty. Stories circulate around school about the trial prosecuting suspects for crimes committed at San Sabba. In and out of class, grandchildren comb through the fates of their grandfathers, schoolteachers scour the past of their fathers, some aloud, some at a whisper. People divide into warring camps, plant themselves in cafés, evade each others’ eyes, turn away, the air around them thick with heavy breathing. Bundles of the past sprout on all sides. They swing like rotten cherries from which worms inch.

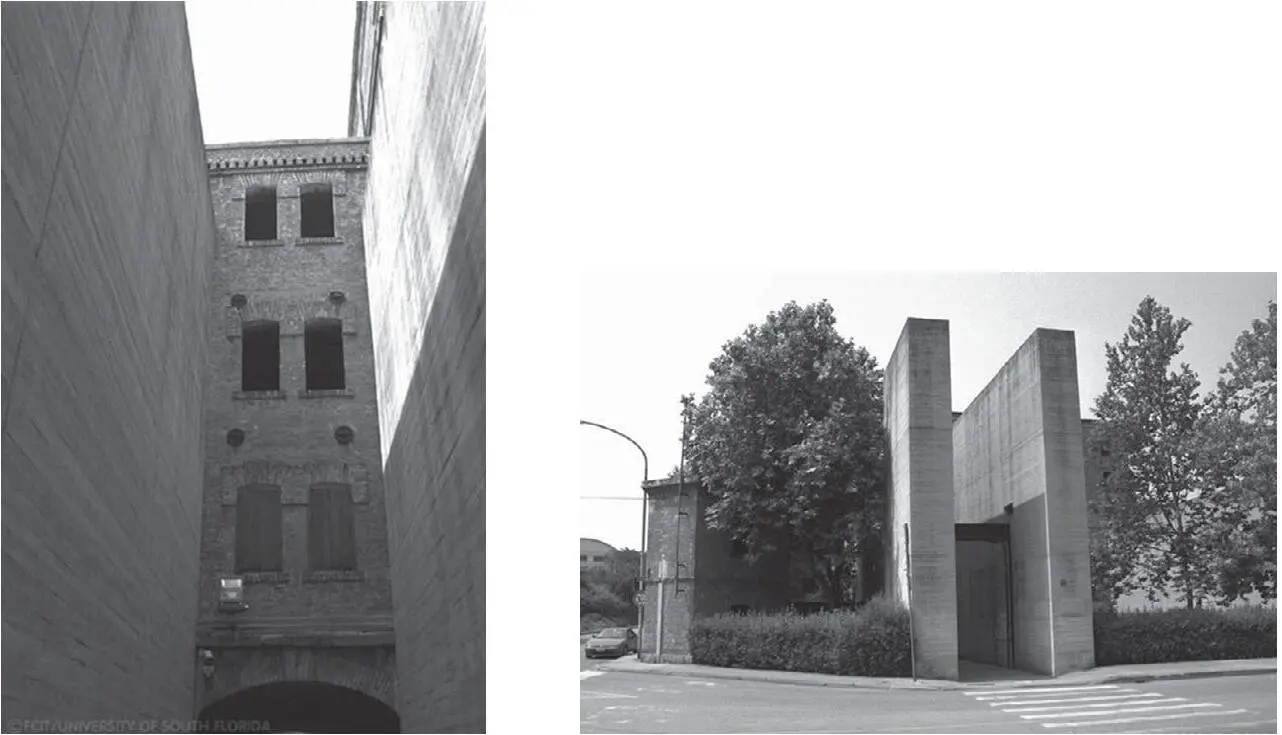

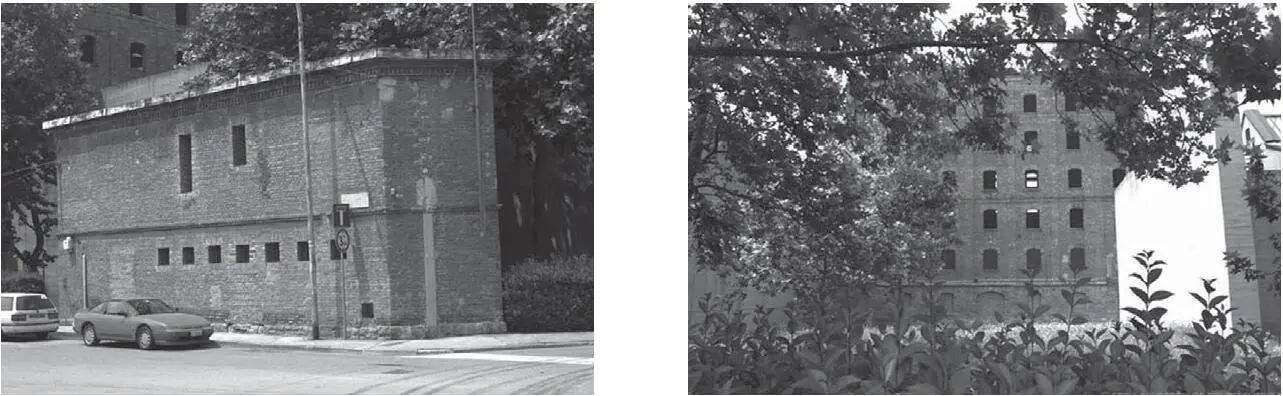

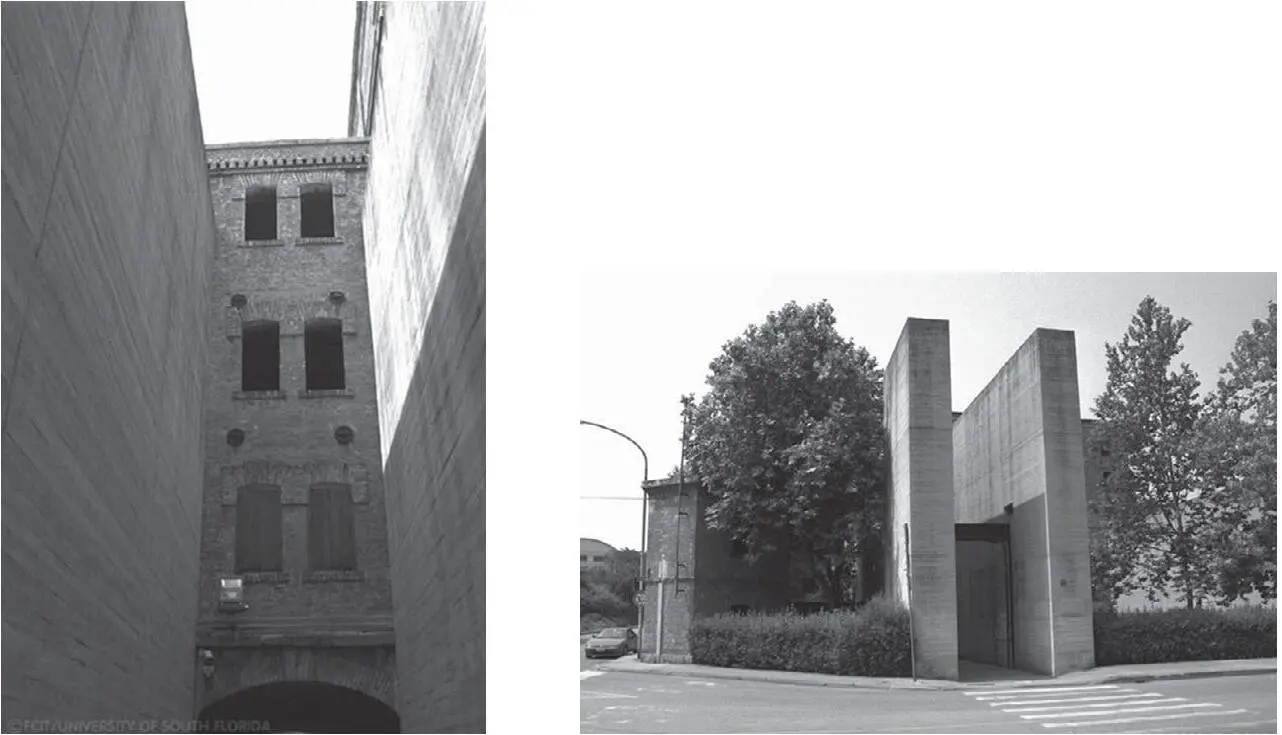

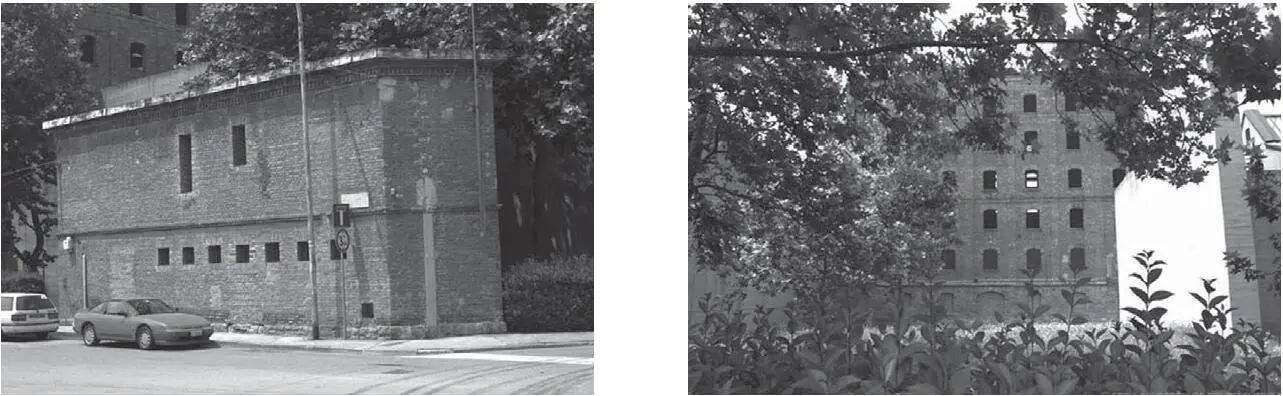

The President of the Republic declares the San Sabba rice mill a national monument in 1965, but at that point, in 1965, few people go to see it, because at the time it is still neglected, abandoned, rats breed there, cats roam through it, mildew wafts from the crumbling façades and a muffled echo circles through its walls. Ten years later the San Sabba rice mill is remodelled. It becomes a museum with mementos in glass cases in which whispers of the dead circle once again.

By car along State Highway 202 (exit Valmaura, Stadium, Cemetery) or, as Haya goes in 1976, taking bus Number 8, 10, 19, 20, 21 or 23 from Trieste, one arrives at the Ratto della Pileria 43. Every day (except 1 January and 25 December) between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m. (admission free) one can step into the well-washed, indescribably quiet past; the barking of dogs does not reverberate; the oven has been demolished; there are no soldiers’ boots marching; the cells are empty: there are no groans, no ash; in the late evening hours no music swells; there is no licentious women’s laughter; no-one is dancing; it’s only shadows that flicker. History is served on a platter in a tidy fashion, sifted, polished, compressed into the grains that roll around noiselessly on the stone floors of San Sabba.

So, in 1976, when the trial begins to prosecute those suspected of committing crimes at San Sabba. Haya says, It is time, yes, and with a camera around her neck, in October 1976, she goes for a

Visit to the rice mill of San Sabba

In 1943 the Nazis move into a plant for husking rice, which at that point was empty, built in 1913 on the outskirts of Trieste, in the town of San Sabba. Inside the walls of the former factory compound stands a complex of buildings, a little city, architecturally almost entirely preserved. So with minor adaptations the Germans change the buildings into a prison, a camp, a “transit camp” from which people travel a long way by train to Auschwitz and Dachau, then briefly, with speed and efficiency, from their cells to the crematorium ovens, right there, not ten metres away. In San Sabba about a hundred and fifty people, Italians, Slovenes, Croats, Jews, Roma, partisans, children, homosexuals, age makes no difference (the Nazis don’t split hairs, everything and everyone gets a pass when the S.S. police and S.S. troops lay their hands on them), about a hundred and fifty people disappear daily in the spanking-new oven, the work of the skilled and proud mason Erwin Lambert, the designer of crematoria. The oven at San Sabba is still there on Saturday, 28 April, 1945, but on Sunday, 29 April, 1945, the Nazis blow up the chimney, demolish the crematorium building and remove all traces that can be hastily removed. On Monday, 30 April the detachments vanish — heading for Carinthia. Between three and five thousand souls are killed, following rules and regulations, in a tidy fashion; the job is done. Perhaps it could have been done better. Perhaps there could have been more incinerations, but, heavens, war is unpredictable. The liberators find three paper sacks for cement under the rubble of San Sabba, and in them human bones and ash which the fugitives have not had time to transport to the San Sabba docks, they are in such a hurry to flee. The little collective grave of the nameless shoved into these paper sacks is therefore saved, because the pelting rain of April 1945, perhaps intending to rinse clean the earth before the advancing summer, to set it to rights for a new age, decides suddenly to stop, as if it has had a change of heart. So, thanks to the heavens, the ashes of the last to be incinerated at the San Sabba rice mill are not turned into grey, squeaky mud from which children would make patty cakes had they passed through there, but instead become a burden few know what to do with, even many years later, some fifty years down the road.

I used to work at the rice mill. During the war I’d stop by the landing stage, partly out of nostalgia, partly to pick up an odd job. The Germans brought sacks of human ashes there. I saw. The sacks were bursting, the ash was leaking out. Charred, halfburned human bones floated on the sea. I saw them. I am Luigi Jerman from Kopar. I live in Trieste.

The Allies manage to catch the occasional fugitive; most elude their grasp. The Allies do, however, find trunks and jute sacks full of stolen goods, which the fugitives have not had a chance to cart off with them, and which they had spent two years eagerly collecting, because the Nazis are racing off to Carinthia. The Allies then send the stolen goods to Rome, where the sacks and trunks languish for fifty years in the cellars of the Ministry of the Treasury and Finance, waiting for someone to discover them again. Oh, there are all sorts of things in these sacks and trunks: watches, spectacles, combs, jewellery — rings, brooches, chains; there are powder compacts, pipes, beautiful pipes; there is money and bonds, furniture, bank books, insurance policies, silver; there are paintings, carpets, clothing, a lot of clothing, bedding, bicycles, typewriters, cameras; there are large wheels of Parmesan cheese, toothbrushes, tableware, fine porcelain — all of it nothing more than patches, debris, shreds of lives no longer living, of lives of those deported to Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück and San Sabba. There are documents, photographs, camp uniforms, passes; there are drawings, maps and charts with locations where the inmates were buried before the oven started working at San Sabba. Something of this is preserved today at the Ljubljana historical archive. Some of it is at the San Sabba museum along with graphics donated by Zoran Mušić, originally from Gorizia, a Dachau prisoner, a student of Babić’s in Zagreb, who died a natural death, thank God, in Venice in 2005.

Rainer is a big honcho in the Adriatisches Küstenland — THE honcho. He controls all the regional heads and mayors, and determines the rules of behaviour for the collaboration armies, Italian, Slovenian and Croatian, and they obey him, these armies, humbly. Entire fascist military units enter into service in the S.S. forces, various police squads, the Special Inspectorate of Public Security under the command of Giuseppe Gueli, who lives well in lively Trieste, in a large villa on Via Bellosguardo and helps Rainer nab Jews and partisans. Rainer visits San Sabba often. Rainer loves going to San Sabba. A visit to San Sabba is like a little holiday for Rainer, a way to relax. Rainer’s buddies live at San Sabba, his companions from the camps, closed by then, in which they used to party after their hard labours. The central, six-storey building at San Sabba is a barrack; on the upper floors are the quarters of the German, Austrian, Ukrainian and Italian S.S. men, all of them small fry, and Rainer does not linger there. The kitchens and mess halls, clean and aired, are on the lower floors; the staff smile and Rainer is pleased. Outside, a small building is visible from the road, housing the sentries who guard everything and everybody, especially Commander Josef Oberhauser, whose flat is on the ground floor. Friedrich Wirth most often escorts Rainer on the rounds. After Wirth is killed by the partisans in May 1944, Rainer is accompanied by August Dietrich Allers.

Читать дальше