It is January 1944, a Wednesday. A darkness is descending all wrapped in snow-white sparks, resembling the crystals flying into the La Gioia tobacco shop when the door opens, and like magic dust it settles on the golden-yellow wooden counter steeped in the fragrance of tobacco, the fragrance of honey and cherries, over which Haya, like Ada before her, with her index finger traces out her future. With a smile of closely held hope, Haya awaits the last customer that evening. A thirty-year-old German in a uniform comes into her tobacco shop. Oh, he is as handsome as a doll. The German already has the Polish nickname Lalka, but at this point, when she first sees the dashing German, Haya knows nothing of that, the dashing German tells her later, I am no Lalka, you are my Lalka. The German is tall and strong and oh, firm and gentle. The German takes out his Voigtländer Bessa, leans over the counter, looks deep into Haya’s green eyes and says Ein 120 Film, bitte. Ein Kodak, bitte, softly, as if whispering to her breathless by an open hearth— Strip off your clothes . So, after twenty-one years, when the love story of Ada Baar and Florian Tedeschi is already spent and falling away in tatters, the little brass bell on the door of the La Gioia tobacco shop announces the beginning of a new life, ding-a-ling, the beginning of a new love story in the Tedeschi family. And so begins the war romance of Haya Tedeschi and Kurt Franz, because the dashing German second lieutenant, S.S.-Untersturmführer, is named Kurt Franz.

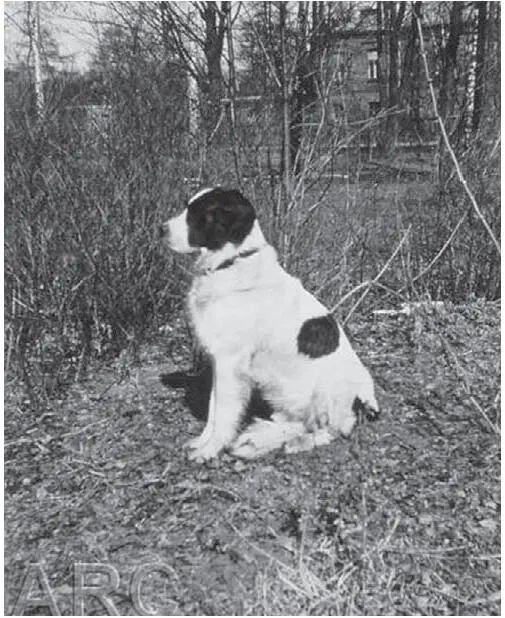

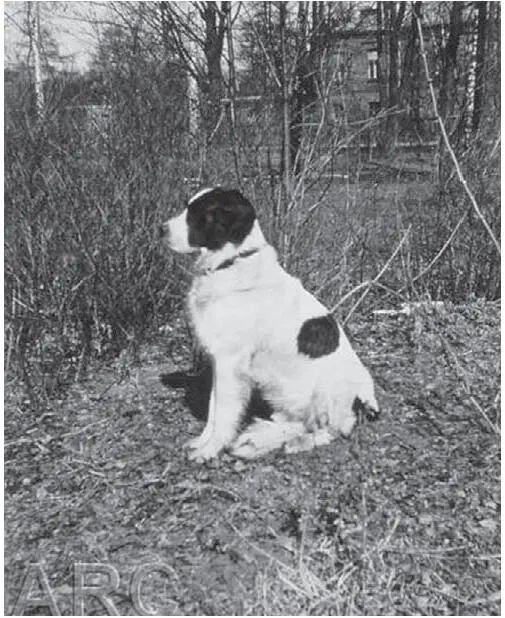

Kurt Franz is a passionate amateur photographer. From his Voigtländer Bessa jump all sorts of little black-and-white scenes, 45 x 60 millimetres; like, for instance, one shot from the Gorizia fortress in the spring of 1944, when Kurt takes a picture of his colleague Willi, after which the three of them, Kurt, Willi and Haya, go out for Kaiserfleisch at the Trattoria Leon d’Oro on Via Codelli. Kurt and Haya meet secretly, of course, in the private rooms of out-of-the-way inns, in the Gorizia suburbs, but they also go for a day’s excursion to Trieste when an engaging opera or operetta is playing, because Kurt likes music and after outings like that with Haya he is awash with a special tenderness. They go to see Lehár’s The Merry Widow, but also Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Verdi theatre. They take in a new film at the Casa Germanica and enjoy a good Apfelstrudel, because Kurt adores Apfelstrudel, because Apfelstrudel reminds him of his mother, whom he also reveres and loves, and Haya has nothing against sweets, but she does prefer panna cotta to Apfelstrudel and they did not offer panna cotta at the Casa Germanica at Via Nizza 15. They, Haya and Kurt, almost always go to matinees so that Haya can be back in Gorizia in time; so that no-one will suspect her passionate love, which, Haya knows, she needs to keep secret. Sundays, Kurt visits Franca Gulli, a violin teacher in Trieste, at Viale Sonnino, where he spends at most two hours playing simple, brief compositions by famous masters, such as a Bach minuet or the Brahms “Lullaby” (“Wiegenlied”), Op. 49, No. 4, or Gershwin’s “Summertime” (with Professor Gulli accompanying on the piano), or Shostakovich’s “Little March” from his pieces for children, because Kurt genuinely loves music. Haya, meanwhile, goes to church, each time to a different one. At church she makes a full confession, is given absolution, and then everything is fine. Kurt tells Haya all sorts of pretty tales. He talks the most to her about his dog Barry; his big beautiful mutt who looks like a St Bernard, but he had to leave it back in Poland, where he used to work at a park on the edge of a beautiful forest near a charming little railway station where there was a zoo with pheasants and rabbits, which he, Kurt, knew how to serve up like a master chef, because he was trained, among other things, as a cook, and where he took so many great photographs, which he keeps in a special photo album called “Schöne Zeiten”, meaning “The Good Times”, and under the title he writes “Die schönsten Jahre meines Lebens”, meaning “The most wonderful years of my life”, although now, while he is with Haya, he says he’s no longer so sure they were.

From Kurt Franz’s album, photographs given to Haya Tedeschi in Gorizia in 1944

Kurt Franz on an outing with Haya near Gorizia in May 1944

Kurt Franz, October 1937

Kurt Franz with his mother in Düsseldorf, 1937

Kurt’s beloved Barry, 1943

In late March 1944 the Tedeschi family move to Milan. Florian gets a job through his contacts there. Being a capo ufficio in a firm engaged in the distillation of molasses seems like dignified work to Florian, compared to selling umbrellas at the Della Tre Venezie in Gorizia. Haya says I am not going. I need to look after the shop, and she stays with Aunt Letizia; in good hands, her mother believes. From Milan Haya’s sister Nora writes and calls. Roses are not blooming, it seems, for them there. The family arrive in Milan by train on a cold and rainy night just as the city is under air attack, the same way the Tedeschi family arrived in Venice after leaving Albania back then — ah, these repetitions, these wartime coincidences, Nora complains to Haya, and there they all perch on their suitcases, she, Nora, Paula, Orestes and Ada, they are drenched for hours at night in the pouring rain at the corner of Via Broletto and Via Bossi, waiting for Florian to bring the keys to a flat, and the bombs are falling, incendiary bombs, Mama Ada says, who is drunk as soon as night falls, people die from bombs like these, she says. The office, the distillery — whatever it is, where Papa works — is on the outskirts of town, all the way out of Milan, Nora writes, and they live in a house that has been allotted to them as refugees, which she, Nora, cannot understand, because the people around them are Italians, although there are plenty of Germans, too — so how can they be refugees? But Ada says things are like that in wartime: civilians are forever on the run, mostly going to where they have family, where they think they’ll be safe, and she, Nora, no longer knows who is “them” and who is “us”, she writes, because in Albania at first they weren’t refugees, then overnight they were, writes Nora. It’s not very nice — the house where they are living — writes Nora. They are on the second floor, and on the first floor are some crude people who speak no Italian and greet them in German with Heil! Maybe these people are refugees, too, writes Nora, there is always shooting going on, so none of them — she or Paula or Orestes — attend school, too dangerous , Papa Florian says, and she is already old for school anyway, she writes, soon she’ll be turning eighteen. Papa, Nora writes, has found her a place in “his” company, and she is already working there as a translator from the German and as a typist, so now every morning she goes with Papa on the local train to work. The Underwood typewriter is so big and cumbersome to type on, writes Nora. There are no dictionaries and she often asks the German soldiers for help. They seem to be everywhere, writes Nora, and they aren’t the least bit unpleasant, in fact, they are courteous, there are even good-looking men among them, just as Haya told her about how decent Kurt is. The trains are packed, the electricity often goes out, and they travel an hour or more to work every day, and the bombs are always dropping, writes Nora, and besides they do not have enough to eat, life was better in Gorizia, she writes. One day Paula took Florian’s bicycle, Florian bought a new bike, really light, aluminium, writes Nora, and she went into a field to steal a few potatoes, but they saw her so she ran off and now they do not have the bike any more, writes Nora, and they are all turning yellow from the carrots. In early May Nora writes that on 21 April she and Florian barely survived when they were on their way home from work, they had heard shooting all day, which was pretty normal, but there was something terrible going on at the train station, total chaos, people were saying that Milan had fallen into the hands of the partisans, in any case, writes Nora, the Germans seem to know they are losing the war, some are even deserting, and she and Papa Florian walked for five kilometres, and, sure enough, the partisans showed up and shoved people around, they were really rough, they had the people line up and walk towards Milan; and they, Nora and Florian, did not walk along in the middle of the road, they walked along the edge, by the ditch; and she saw dozens of dead bodies, writes Nora, mutilated bodies, actually, in the ditch, the handiwork of the partisans for sure; and she writes that she was amazingly lucky to be alive, because she had on her a membership card for the Fascist Republic of Salò, and if the partisans had found it they definitely would have killed her, but luckily they did not touch her, writes Nora, and she writes how the partisans during those days did many bad things, and then, thank God, the Allies got there. She almost started crying, writes Nora, when she saw how in the courtyard of a school they were shooting a fascist whom they’d caught. They stood him up against a wall, writes Nora, and gave this ten-year-old boy a gun — the boy was no older than ten, not a day over ten, like our Orestes, writes Nora — and ordered the boy to shoot, because he, the fascist, had killed the boy’s father. Shoot! they shouted, and the little boy did not know how, writes Nora, and all that, the shooting, ended badly: the boy shot and shot and the fascist kept not falling, he just bled more, then they killed a few Germans who wouldn’t surrender, right there in front of us. This is what Nora writes.

Читать дальше