Onset of advanced cellular decay: two minutes.

“Something is the matter with her brain.”

“You don’t know that.”

I do not know what else to say. I say this:

“I will take the dog.”

“Can’t stand to see her gassed?”

“I will take the dog.”

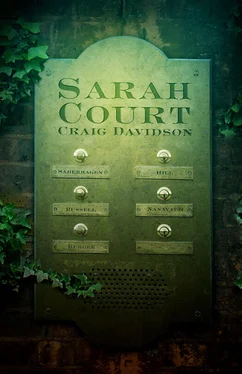

My employeris entombed in a wheelchair. Bandages clad his head, eyes, to the midpoint of his nose. Hands encased in gauze. He appears to have shrunk several sizes. His body is like an alpaca sweater sent through the wash. There is a large depression in the side of his head. A wet, red, glistening hole like a medical photograph of someone’s wrecked vocal cords. Tonight he will be visited by Nicholas Saberhagen. My presence a precautionary measure. The dreadlocked kid, Parkhurst, who my employer says is a biographer of some sort, is curled up in a corner. I saw this person, Parkhurst, not too long ago. In the company of Colin and Wesley Hill.

When Nicholas Saberhagen arrives, I observe unnoticed from the top of the stairs. Nicholas asks permission to photograph the box. There is some commotion in the viewing chamber. Nicholas brought his son with him, you see. Somehow the fat vampire boy got into the viewing area with the box. Next Nicholas is bundling his son into the car. I follow them in my minivan. They pull into the Motor Motel. I park in a washout. The dark fluttering of wings in the trees. Time goes by. Nicholas exits his room in a towel. He retreats inside.

Next: bracing animalistic screams.

I get out of the car, walk across the road. The boy is lying on the motel carpet. Rope burns ring his neck. Nicholas Saberhagen pushes at his chest. He spies me. As if to spy a demon. I kneel beside them. There is a visible dent in the boy’s throat.

“Your boy’s trachea is crushed.”

In my pockets: a notebook, a pen, a penknife. I chew off the pen’s cap. I pry out its ink wand.

“The fleshy tube running down the boy’s neck. You must cut below the obstruction.”

“Do you have any idea what you’re doing?” says Nicholas.

“The veins run here”—I trail a finger down the boy’s neck—“and here. I know to avoid them. I know the trachea’s consistency is that of a garden hose. I know about how hard to push.”

I kneel patiently. The towel has fallen away from Nicholas’s body. There is a dark stain on the tip of his penis. The boy’s skin is presently the blue of a picture-book sea.

“Okay, Jeffrey. Go. Go.”

I straddle the boy’s waist. Set the knifetip horizontally across his windpipe below the Adam’s apple. Drive the knifepoint in, then squeeze either side of the wound. Still too small. Insert my pinkie finger. The boy’s tendons constrict around my fingertip. His slit trachea feels like a calamari ring. I thread the pen barrel in. Nicholas wraps the towel round his boy’s throat. I find the carotid snaking past the boy’s collarbone. Pressure stems the blood flow.

A man enters. He has the look of a SAD cowboy. His consort: a half-naked woman with a harelip.

“We called the medics.”

A medical evacuation helicopter touches down in the gravel lot. I stand in the rotor wash as it lifts off. The helicopter ascends until it is nothing but a blinking red dot.

I return to the motel room. The closet door smashed. Contents of the boy’s knapsack spilled over the carpet. Electronic equipment in Ziploc baggies. On the cover of his math booklet is a girl’s name. Encircled by a lopsided heart. I know that name.

General hospital.Lea side of Valleyview Road past the ambulance bays. Midnight. Patience Nanavatti sits in the passenger seat of my Vend-O-Mat Dodge Sprinter. On my lap is a box of cellulose packing peanuts.

“It is sensible.”

“You keep saying that. How will she breathe?”

“I will punch holes in the boxtop.”

“She’s not a turtle.”

I stack cases of soda onto a dolly. Patience sets Celeste gently into the bed of packing material. She moans when I close the flaps.

“I’m a bad mother, I guess.”

“But she is not your child. She never was.”

I have made Patience Nanavatti SAD. I cannot understand why she should react so. I merely outlined the truth of the matter.

The elevator takes me to the fifth floor. As I am pushing the dolly round a blind corner, I nearly collide with a nurse. The nurse’s patient is Abigail Burger.

Abigail is narcotically swollen inside a hospital gown. Her feet are covered in thick strings of blue veins, which I can see through her green paper shoes. The flesh of her face hangs in bags, as if fishing weights have been sewn under her skin.

“Gruh!” goes Abigail Burger. “Gruh!”

The most purely FRUSTRATED sound I have ever heard. Her breath is as sweet as baby food. She reaches for me. So strong. The nurse struggles to keep her in check.

“No soda machine up here,” the nurse says. “You want the caf.”

I double down the corridor into the neonatal ward. I carefully set Celeste in a plastic tub. Pluck stray peanuts off her blanket. To the tub I affix a note:

FORGIVE ME.

I pullinto the horseshoe driveway of my employer’s cottage. The moon stands upon its exact reflection on the lake. Hours ago he called:

“Je… uuuuuurt suh— suh …”

Then the phone line went dead.

I open the cabin door. All is very quiet. Except a cupboard rattles under the kitchen sink. I open it. The dreadlocked one, Parkhurst, has squirmed underneath. His body is bent round the gooseneck projection of plumbing pipe. His face appears ovencharred, but no: only blood dried to a glaze.

I shut the cupboard.

In the viewing chamber, the casement windows open upon a starless sky. A squirming mass the size of a medicine ball occupies my employers’ wheelchair. On the floor beside it are empty bandage casings that still hold the strange shapes of whatever they once encased.

Inside the box is something holding the exact shape of my employer. Its skin is grey yet gleaming, silvery, shifting in the insubstantial light the way campfire embers will brighten in the wind. But as I watch, its flesh is paling to match the colour of my own. Its eyes are blobs of mercury in creased sockets. With one fingertip the thing traces the box where each pane meets.

“Whoever built this did a very adequate job.”

It opens its mouth against the glass. Puffs its cheeks like a blowfish. Deep down in its craw, little half-seen things are thrashing. It has no nostrils. But the quivering ball in the wheelchair has two slit-like dilations, side by each, fluttering in the manner of fish gills. They are the only feature it has, anymore.

“Are you scared of me?” the thing in the box asks.

I say: “I do not know what I am.”

“If it makes you feel any better, neither do I.”

It yawns. Blood emits from my nose.

“Eat the hearts of the innocent,” it says. “Is that what you think I’ll do?”

I say: “What will you do?”

“Go to Disneyland?”

“What are you?”

“Some call me demon, some say alien. Demon as it fits a ready-made definition, I guess. Alien as I don’t match any categorized flora or fauna on earth. I wish I knew what I was. You are lucky to be part of a species.”

It stretches, catlike. Snaps its jaws.

“Want to hear something funny? Although I don’t know if it is. That whole concept is lost on me.”

“Me, too.”

“Your species finds it impossible to envision an alien entity lacking the body structure, appendages in some arrangement, of organisms found on your planet. Your most common alien representation? The “Grey Man.” Big globe-like eyes. Legs, arms, fingers, toes. Or if not human-shaped, then spiderlegged. Or tentacle armed. Still legs, still arms. Or exactly the same bodily specifics as you, except furry. All with eyes and mouths: only more or fewer than you, or smaller or larger. Your imaginations can only conceive of organisms here, on this planet, reconfigured. Do you understand the mammothness of the universe? That there must be life hieing to no forms found here on Earth? Creatures without heads, or eyes, or organs. Only human beings are self-absorbed enough to believe all life in the universe must resemble them.”

Читать дальше