He stands up and goes to the entrance of our room. He follows Fatima as she bends over her squeegee. She stacks up the rag on its blade with her hands. He waves at her to unfold it and then fold it up again into one straight piece. She finishes cleaning the room. She sits down on the edge of the bed to change the sweaty pillow cases. I’m waiting uncomfortably for her to get up and move away from the bed. Father swats at the flies with a towel. She says that her husband bought a can of Mobiltox to kill insects, from the shop attached to the petrol station. Father says: “You mean you know about Mobiltox too?” She says: “So because I’m a fellah that means I’m ignorant?” She brings in the long rug that she hung over the ledge of the balcony. She asks my father: “Shall I spread it on the ground, Sidi?” He replies: “No. It’s hot as hell. Fold it and put it under the bed.”

The sound of the watermelon vendor comes in from the window. Father goes out to the balcony. He calls to him: “Are they ripe?” “Of course, Bey.” The seller picks one up and thumps it with the flat of his hand. He puts it back and picks up another one. He thumps again. Father starts to say something, but the seller cuts into it with a knife. He makes a square opening in its side. He turns it over and pulls out a piece that is bright red, then he sticks it back into place. He puts it to the side and picks up another one. Father calls out: “One’s enough.” He bends over and takes the cut watermelon from him. He gives him his money. He takes it to the sink and washes off its surface, taking care not to get water in its opening. Then he puts it on a tray on top of the sideboard. He brings a piece of cheesecloth from the dresser and covers it.

We get ready to have lunch. Father notices that the okra in red sauce has turned sour. She says she forgot to boil it yesterday. I wait uneasily for father to explode, but he doesn’t say a word. Instead he sends her to buy head meat from the Husseiniya market. I say: “Shall I go?” He says no. She goes to the storage room and comes back wrapped in her black coat. He gives her some money. He repeats to her: “Forehead, eye, brain, and tripe.” He runs after her and yells down the stairwell: “Don’t forget the pickles and arugula.”

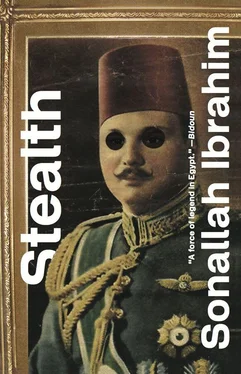

He takes the envelopes back to the room and throws them on top of the desk. I pick up a picture with some man wearing a big overcoat that goes down to his shoe tops. His fez covers his forehead and comes down almost all the way to his eyes. His thin moustache twists upwards. His right hand is behind his back and his left fist sits on the table. A big vase sits on the ground with the end of a curtain hanging on it. The picture is old and its edge is torn. I turn it over. Nothing. I show it to father. “Who’s this?” He takes it and studies it for a while. He says: “It’s me.”

“You?”

“Yeah, when I was eighteen.”

I show him another picture of a man in a winter coat. The fez is again close to the eyes and the moustache twisting upwards. He’s sitting in a chair with his left elbow on an armrest that has a lion’s head on the end of it. His thumb is propped against his cheek. The other hand has a cigarette holder between the index and middle fingers. The sleeve of his pressed shirt shows a button at his wrist. He says: “That’s me too — after I married Nabila’s mother. I was about twenty-seven.” I turn over the picture and read my father’s full name written in red pencil. The handwriting is my mother’s.

I recognize him easily in another picture. He’s in a fancy suit, resting his hand on the handle of a walking stick. His back is leaning against a brick wall. He looks very handsome. There’s a beautiful boy next to him in a suit with two rows of buttons. A folded handkerchief dangles from the breast pocket of his jacket. His short trousers stop just below the knee, at the tops of his long socks. I flip over the picture: “Respected Mr. Khalil Effendi with his son during Eid of 1928.” Underneath is my brother’s signature.

In the last picture, he looks the way he is now. He’s sitting down, reading in a full suit. His fez tilts back. The glasses are sliding down his nose. The wrinkles in his neck show over the collar of his shirt. On the back of the picture, he’s written in his own hand: “1945.”

Fatima comes back with a wrapper full of head meat. She puts it in a plate on top of the table and takes the arugula to the kitchen. Father shouts at her: “Wash it well.” He waves at her to come and eat with us. I get mad and think about not eating anything if she does come. She says she has to make tomorrow’s food for her husband. He puts a piece of meat in a half loaf for her. She takes it and thanks him.

I get out of my chair and drag it to the table. I notice a small picture on the floor. It must have fallen from the envelope. A small girl wears a dress with short sleeves. Her face is round and her hair is curly. She has short boots on. Her right hand rests on her stomach and her left sits on a stone wall. There’s a strange look in her eyes. Fear? Worry? Anger? I recognize father’s neat handwriting on the back, “middle of 1921.” I give it to father asking: “Who’s this picture of?”

He answers curtly: “Your mother.” I stand on top of a chair in my white summer pyjamas with their short sleeves. My elbows are leaning against the windowsill. I watch the people walking. The sun moves close to the edge of the window. I jump down to the floor and go out to the hall. The voice of mother comes from the kitchen, singing: “I’m going to hide my pain.”

We get off the tram at the Lazoghly Square stop. I stare at the head of the statue wrapped in its big turban. We pass in front of a grand café with shiny mirrors covering its walls. The café’s at the corner of two streets that come to a dead end in the square. Two of father’s friends wave at him and invite him to join them. He signals to them that he’s headed to the next building, and that he will pass by them on the way back.

We cross the street to an old building. We go in through an open door. We walk through a long hallway crowded with old men. There is an old man in a full suit. He’s shorter than father. He leans on a stick and has trouble walking. His face is so white it hits you. White hair appears at the rim of his fez. We get close to him and try to go around him, but he stops father. Father looks at him surprised. He says to father in a shaky voice: “Khalil Effendi? I am Rifqy.” Father greets him a little embarrassed and says: “How are you, Rifqy Bey?” “As you can see.” Father says: “May God give you health.” The old man looks at me and asks: “Your grandson?” “No, my son.” “God does provide! How are his exams going? God willing, he’s passing them?” Father says: “He has an English makeup exam.”

We leave him and keep on walking. Father’s steps slow down. The smile that he had drawn on to his lips as we went out disappears. We stand in a queue that ends at a glass window that has the word “cashier” written in cursive script that forms a circle, and underneath it is a foreign word.

A man with a thick laughing face comes up to us. He greets father warmly. He asks him why he doesn’t come to the meetings of the group. Father makes excuses about the duties of daily life. He asks him what happened with the special lawsuit over the partial liquidation of retirements. The man shakes his head unhappily: “It looks like there’s no hope. The government’s dead set on stealing from us.” “What can we do?” “We have to retain a big shot lawyer.”

The queue moves. We find ourselves in front of the window. Father takes the withdrawal slip for his retirement payment out of the jacket of his suit coat. He gives it to the clerk sitting behind the window. The clerk hands several pounds over to him. Father signs a receipt of acknowledgment.

Читать дальше