She drags the bed frame away from the wall. She lights the primus stove, then carries it in her hand and bends over the metal box springs. She holds shut the opening of her gallabiya that almost exposes her breasts. Father puts on his glasses. He tells her: “Give it to me.” He takes the burner from her and squats down next to the frame. He sets the stove under the hole that the box springs rest in. I lean over next to him. I study his strong hands that hold on to the stove so firmly. I notice some bedbugs in a row. The fire touches them and they burst into flames and fall to the ground. I point out one that is getting away. He catches up to it with the flame. He turns around with the stove and goes to the other side of the frame. She brings him a bottle of paraffin and he pours from it on to the burnt spots. He tells us to look carefully around the sides of the mattress and the folds of the pillows.

“Give me the jug.”

She brings a jug of water from the living room. He sips from it, then wipes his lips with the sleeve of his gallabiya. He says: “It’s hot. Put it on top of the sideboard in the breeze.” She says: “Shall I go get some ice, Sidi?” As she speaks, her mouth opens and shows her yellow teeth. He answers: “No. Not now.” The ice seller is at the door. He’s carrying half a block wrapped in canvas. He puts it on top of the dinner table. Mother carries it to the kitchen. She breaks off a piece with the handle of the wooden pestle, then bangs at it to make smaller pieces. She rinses it with water and scatters it over the plates of paluza, the white pudding, lined up on the top of the sideboard. We eat it sitting next to the window.

He drags the desk chair over and stands on top of it. Gently, he brings over the wall clock. He hands it to Fatima as he says: “Take it easy. Be careful.” She puts the clock over the frame of the bed. She brings a piece of cloth and wets it with the paraffin. She goes to clean off the clock, but he stops her and gets down. He takes the cloth from her. He wipes off the sides of the clock with it. He opens its glass pane. Wipes the edges around the clockwork. He asks her for the bottle and another piece of cloth. She gives him an old wool sock. He wets it with the paraffin. He takes hold of the pendulum and rubs it well. He carefully wipes off its roman numbers. Then he takes a small can about the size of his hand with a little spout on top. Puts the spout under the clockwork and tilts it to pour out what’s inside. He pours into the two openings in the middle of the ring of numbers and wipes off a small, shiny brass opening. He presses it into one of the openings and turns it gently. Moves to the other one. Turns the key several times until it won’t go any more.

He takes the clock to the hall and puts it above the table. His eyes move from one wall to another. He settles on a spot between the door on to the skylight and the door to the guest room. Fatima takes one of the dining chairs and brings it to the place he has fixed on. He climbs up on to the chair. He asks me for the hammer and a medium-sized nail. I run back to the room. I get down on my knees in front of the bed and pull out the hammer and a cardboard box from underneath it. The box is full of nails, bits of electric cord, tacks, and parts from light fixtures. I pick out some nails that are different sizes. I run back. Father stretches his hand out to me. Fatima snatches away the hammer and nails and hands them to him. He chooses one of the nails and pounds it into the wall. His strokes are strong and sure.

I go over to the door of the constable and Mama Tahiya. I look in the keyhole. There is no trace left of their bed or their chiffonier. They took all their furniture when they moved to their new place. Father shouts at me: “Where are you?” I rush back. He stretches out his hand with the hammer in it, but Fatima takes it before I can. The hammer almost falls between us and he tells me: “You’re good for nothing.” He asks her to gently bring him the clock. She brings it to him. He hangs it on the nail. He takes its pendulum from her and fixes it under the clockwork. He swings it on and the clock starts to work. He closes the glass and climbs down.

We go back to the room. He asks her to take down the framed pictures. She gets up on the chair. Her scarf gets hung on the side of the wardrobe. She pulls it out and ties it again over her thick hair. Her gallabiya gathers up in her crack. She sticks her hand out and straightens it. Father’s eyes fix on her small bottom. She takes down a picture and gives it to him. It’s big, with a wide wooden frame and has small egg-shaped head shots in one row after another. I know father’s picture is in the second row from the bottom. ’Azmi, the son of Mama Basima’s cook, has taken it out once. Father dusts it off with a rag and puts it on top of the box.

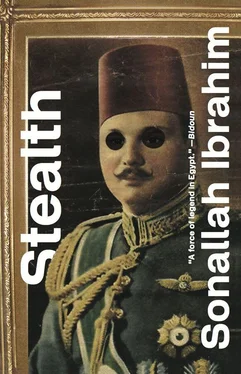

She gives him another picture. It shakes in her hand. He yells at her: “Your hand’s wobbly!” The picture shows him sitting in the middle of several army officers. Smiling in a fancy uniform. His shoes are shiny and have pointy ends. His hand is wrapped around a fly whisk that rests in his lap. His moustache turns up on the sides, like the moustache of King Fuad.

A third picture has a fine wooden frame with something that looks like a cross in each corner. He stands between two officers. One of them wears puffy pants tucked in high boots that come up to the knee. The shoulders of their uniforms have small, steel swords that show they’re officers. He takes hold of the picture in his hand and stares up at the wall as if searching for a place to hang it. I say: “Shouldn’t we put a glass pane over it first?” He shakes his head as if he’s sad: “May God have vengeance on them.” Mama Basima with ’Azmi goes out all mad and leaves us with his mother, the cook. We start to gather up our things in canvas bags. He puts the big pictures in grooved frames in the bag and ties it with string. We stack what we need next to the door. We put on our clothes and get ready to leave. I go to the toilet to pee. I trip over the water bucket and it spills. The cook yells at me: “Are you blind?” He yells back at her: “Shut up!” She runs to the door. She opens it. She grabs one of the bags. She throws it over the ledge of the stairwell. She grabs another. We rush out and go down. The bag of pictures comes after us. It crashes at the bottom and I hear the sound of breaking glass.

Fatima takes the pictures back to their place over the dresser. He points at a yellow envelope and asks her to bring it over. He throws it towards the desk and it falls. She starts to bring in the bedding.

We leave her alone in the room so she can sweep and mop it. Father brings the yellow envelope with him. He sits at the table in the hall facing the door to our room. I stand next to him. He dumps out what is in the envelope. Pictures without frames around them, some of them as small as a postcard. He picks up one and studies it. I lean over his shoulder. My glasses slide down my nose and I put them back in place. Father is between my aunt and my uncle’s wife. They’re all three wearing white gallabiyas. Only father, in his skull cap, wears anything on his head. The hair of my aunt and uncle’s wife is black like charcoal. It’s short and thick and gathered around their faces. Nabila is standing in front of my father’s legs. Behind them, there’s a wall made of reeds, and in front of them, a beach. I ask him: “Where’s this?” He says: “In front of our cabin at Ras al-Bar.”

He puts the picture to the side and picks up another. A crowded beach. Father, his face full of laughter, is in a white suit coat, a fez, and a necktie. He’s holding a cigarette. I don’t know any of the people in the crowd next to him except my brother, who is wearing a bathrobe.

Читать дальше