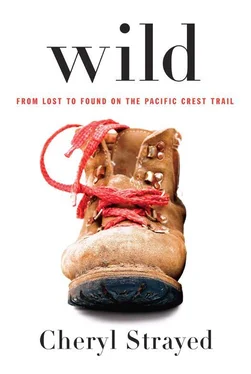

Cheryl Strayed - Wild

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cheryl Strayed - Wild» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Wild

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:978-0-307-95765-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wild: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Wild»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Wild — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Wild», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You know that isn’t a real book,” I’d said disdainfully to my mother when someone had given her Michener’s Texas as a Christmas gift later that year.

“Real?” My mother looked at me, quizzical and amused.

“I mean serious. Like actual literature worth your time,” I replied.

“Well, my time has never been worth all that much, you might like to know, since I’ve never made more than minimum wage and more often than not, I’ve slaved away for free.” She laughed lightly and swatted my arm with her hand, slipping effortlessly away from my judgment, the way she always did.

When my mother died and the woman Eddie eventually married moved in, I took all the books I wanted from my mother’s shelf. I took the ones she’d bought in the early 1980s, when we’d first moved onto our land: The Encyclopedia of Organic Gardening and Double Yoga. Northland Wildflowers and Quilts to Wear. Songs for the Dulcimer and Bread Baking Basics. Using Plants for Healing and I Always Look Up the Word Egregious . I took the books she’d read to me, chapter by chapter, before I could read to myself: the unabridged Bambi and Black Beauty and Little House in the Big Woods . I took the books that she’d acquired as a college student in the years right before she died: Paula Gunn Allen’s The Sacred Hoop and Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior and Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s This Bridge Called My Back . Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass . But I did not take the books by James Michener, the ones my mother loved the most.

“Thank you,” I said now to Jeff, holding The Novel . “I’ll trade this for the Flannery O’Connor if you’d like. It’s an incredible book.” I stopped short of mentioning that I’d have to burn it that night in the woods if he said no.

“Absolutely,” he replied, laughing. “But I think I’m getting the better deal.”

After lunch, Christine drove me to the ranger station in Quincy, but when we got there, the ranger I spoke to seemed only dimly aware of the PCT. He hadn’t been on it this year, he told me, because it was still covered with snow. He was surprised to learn I had. I returned to Christine’s car and studied my guidebook to get my bearings. The only reasonable place to get back on the PCT was where it crossed a road fourteen miles west of where we were.

“Those girls look like they might know something,” said Christine. She pointed across the parking lot to a gas station, where two young women stood next to a van with the name of a camp painted on its side.

I introduced myself to them, and a few minutes later I was hugging Christine goodbye and clambering into the back of their van. The women were college students who worked at a summer camp; they were going right past the place where the PCT crossed the road. They said they’d be happy to give me a ride, so long as I was willing to wait while they did their errands. I sat in the shade of their lumbering camp van, reading The Novel in the parking lot of a grocery store as they shopped. It was hot and humid — summertime in a way that it hadn’t been up in the snow just that morning. As I read, I could feel my mother’s presence so acutely, her absence so profoundly, that it was hard to focus on the words. Why had I mocked her for loving Michener? The fact is, I’d loved Michener too — when I was fifteen I’d read The Drifters four times. One of the worst things about losing my mother at the age I did was how very much there was to regret. Small things that stung now: all the times I’d scorned her kindness by rolling my eyes or physically recoiled in response to her touch; the time I’d said, “Aren’t you amazed to see how much more sophisticated I am at twenty-one than you were?” The thought of my youthful lack of humility made me nauseous now. I had been an arrogant asshole and, in the midst of that, my mother died. Yes, I’d been a loving daughter and yes, I’d been there for her when it mattered, but I could have been better. I could have been what I’d begged her to say I was: the best daughter in the world.

I shut The Novel and sat almost paralyzed with regret until the women reappeared, rolling a cart. Together we loaded their bags into the van. The women were four or five years younger than me, their hair and faces shiny and clean. Both wore sporty shorts and tank tops and colorful strands of braided yarn around their ankles and wrists.

“So we were talking. It’s pretty intense you’re hiking alone,” said one of them after we’d finished with the bags.

“What do your parents think of you doing it?” asked the other.

“They don’t. I mean — I don’t have parents. My mom’s dead and I don’t have a father — or I do, technically, but he’s not in my life.” I climbed into the van and tucked The Novel into Monster so I wouldn’t have to see the discomfort sweep across their sunny faces.

“Wow,” said one of them.

“Yeah,” said the other.

“The upside is that I’m free. I get to do whatever I want to do.”

“Yeah,” said the one who’d said wow.

“Wow,” said the one who’d said yeah.

They got into the front and we drove. I looked out the window, at the towering trees whipping past, thinking of Eddie. I felt a bit guilty that I hadn’t mentioned him when the women asked about my parents. He’d become like someone I used to know. I loved him still and I’d loved him instantly, from the very first night that I met him when I was ten. He wasn’t like any of the men my mother dated in the years after she divorced my father. Most of those men had lasted only a few weeks, each scared off, I quickly understood, by the fact that allying himself with my mother meant also allying himself with me, Karen, and Leif. But Eddie loved all four of us from the start. He worked at an auto parts factory at the time, though he was a carpenter by trade. He had soft blue eyes and a sharp German nose and brown hair that he kept in a ponytail that draped halfway down his back.

The first night I met him, he came for dinner at Tree Loft, the apartment complex where we lived. It was the third such apartment complex we’d lived in since my parents’ divorce. All of the apartment buildings were located within a half-mile radius of one another in Chaska, a town about an hour outside of Minneapolis. We moved whenever my mom could find a cheaper place. When Eddie arrived, my mother was still making dinner, so he played with Karen, Leif, and me out on the little patch of grass in front of our building. He chased us and caught us and held us upside down and shook us to see if any coins would fall from our pockets; if they did, he would take them from the grass and run, and we would run after him, shrieking with a particular joy that had been denied us all of our lives because we’d never been loved right by a man. He tickled us and watched as we performed dance routines and cartwheels. He taught us whimsical songs and complicated hand jives. He stole our noses and ears and then showed them to us with his thumb tucked between his fingers, eventually giving them back while we laughed. By the time my mother called us in to dinner, I was so besotted with him that I’d lost my appetite.

We didn’t have a dining room in our apartment. There were two bedrooms, one bathroom, and a living room with a little alcove in one corner where there was a countertop, a stove, a refrigerator, and some cabinets. In the center of the room was a big round wooden table whose legs had been cut off so it was only knee-high. My mother had purchased it for ten dollars from the people who’d lived in our apartment before us. We sat on the floor around this table to eat. We said we were Chinese, unaware that it was actually the Japanese who ate meals seated on the floor before low tables. We weren’t allowed to have pets at Tree Loft, but we did anyway, a dog named Kizzy and a canary named Canary, who flew free throughout the apartment.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Wild»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Wild» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Wild» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.