“I can’t stand to think that you’re dead, Dorothy.”

She tore her gaze from the wood chips.

“Dead?” she asked. “Oh, I’m not … Well, maybe you would call it dead. Isn’t that odd.”

I waited.

She returned to her study of the wood chips.

“Are you happy?” I asked her. “Do you miss me? Do you miss being alive? Is this hard for you? What are you going through , Dorothy?”

She looked at me again. She said, “It’s too late to say what I’m going through.”

“What? Too late?”

“You should have asked me before.”

“Asked you before what ?” I said. “What are you talking about?”

Then Mimi King called, “Yoo-hoo!” She popped out her back door, waving. She was all dressed up in her church clothes; she even had a hat on. I waved back halfheartedly, hoping this would be enough, but no, on she came, stepping toward us in a wincing manner that meant she must be wearing heels. I said, “Damn,” and turned back to Dorothy. But of course she wasn’t there anymore.

I knew it was because of Mimi. Why, even while Dorothy was alive she’d had a way of ducking out of a Mimi visit. But somehow I couldn’t help taking her disappearance as a reproach to me personally. “You should have asked me before,” she’d told me. “It’s too late,” she’d told me. Then she’d left.

This was all my fault, I couldn’t help feeling. Mimi was tripping through my euonymus bushes now, but I turned away with a weight in my chest and limped back into my house.

In September, we held a meeting at work to plan for Christmas. Most of us found it difficult to summon up any holiday spirit; temperatures were in the eighties, and the leaves hadn’t started turning yet. But we gathered in Nandina’s office, Irene and Peggy on the love seat, Charles and I in two desk chairs wheeled in from elsewhere. Predictably, Peggy had brought refreshments — homemade cookies and iced mint tea — which Nandina thanked her for although I knew she didn’t see the necessity. (“Sometimes I feel I’m back in grade school,” she had told me once, “and Peggy is Class Mother.”) I accepted a cookie for politeness’ sake, but I let it sit on its napkin on a corner of Nandina’s desk.

Irene was wearing her legendary pencil skirt today. It was so narrow that when she was seated she had to hike it above her knees, revealing her long, willowy legs, which she could cross twice over, so to speak, hooking the toe of her upper shoe behind her lower ankle. Peggy was in her usual ruffles, including a sweater with short frilly sleeves because she always claimed Woolcott Publishing was excessively air-conditioned. And Nandina held court behind her desk in one of her carriage-trade shirtwaists, with her palms pressed precisely together in front of her.

“For starters,” she said, “I need to know if any of you have come up with any bright ideas for our holiday marketing.”

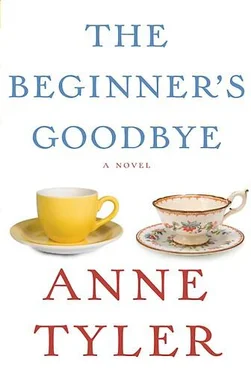

She looked around the group. There was a silence. Then Charles swallowed a mouthful of cookie and raised his hand a few inches. “This is going to sound a little bit grandiose,” he said, “but I think I’ve found a way to sell people our whole entire Beginner’s series, all in one huge package.”

Nandina looked surprised.

“You’ve heard of helicopter parents,” he told the rest of us. “Those modern-day types who telephone their college kids every hour on the hour just to make sure their little darlings are surviving without them. Nothing Janie or I plan to do, believe me — assuming we can ever get the girls to leave home in the first place. But anyhow, this is exactly the kind of gift idea that would appeal to a helicopter parent: we would pack the complete series in a set of handsome walnut-veneer boxes with sliding lids. Open the boxes and you’ll find instructions for every conceivable eventuality. Not just the Beginner’s setting-up-house titles or the Beginner’s raising-a-family titles but Beginner’s start-to-finish, cradle-to-grave living! And the best part is, the walnut boxes act like modular bookshelf units. Kids would just stack them in their apartments with the tops facing frontwards, slide the lids off, and they’re in business. Time to move? They’d slide the lids back on and throw the boxes into the U-Haul. Not ready yet for the breastfeeding book, or the divorce book? Keep those in a box in the basement till they need them.”

“What: Beginner’s Retirement , too?” Irene asked him. “ Beginner’s Funeral Planning ?”

“Or toss them into their storage unit,” Charles said. “I hear all the kids have storage units now.”

Nandina said, “I’m having trouble believing that even helicopter parents would carry things that far, Charles.”

“Right,” Irene said. “Why not just give the parents themselves The Beginner’s Book of Letting Go and circumvent the whole issue?”

“Do we publish that?” Peggy wondered.

“No, Peggy. I was joking.”

“It’s a thought, though,” Charles said. “But only after we sell the other books, obviously. Make a note of it, Peggy.”

“Oh! If we’re talking about new titles,” Peggy said, perking up, “I have one: The Beginner’s Menopausal Wife .”

Nandina said, “Excuse me?”

“This man came to fix my stove last week? And he was telling me all about how his wife is driving him crazy going through menopause.”

“Honestly, Peggy,” Nandina said. “Where do you find these people?”

“It wasn’t me! My landlord found him.”

“You must do something to bring it on, though. Every time we turn around, someone seems to be dumping his life story on you.”

“Oh, I don’t mind.”

“For my own part,” Irene said, “I make a practice of keeping things on a purely professional footing. ‘Here’s the kitchen,’ I say, ‘here’s the stove. Let me know when it’s fixed.’ ”

I laughed, but the others nodded respectfully.

“I promise,” Peggy told us, “this was not my fault. The doorbell rang; I answered. This man walked in and said, ‘Wife.’ Said, ‘Menopause.’ ”

“We seem to be getting away from our subject here,” Nandina said. “Does anyone have a suggestion relating to Christmas?”

Charles half raised his hand again. “Well …” he said. He looked around at the rest of us. “Not to hog the floor …”

“Go ahead,” Nandina told him. “You seem to be the only one with any inspiration today.”

Charles reached beneath his chair to pick up a book. It was covered in rich brown leather profusely tooled in gold, with Gothic letters spelling out My Wonderful Life, By .

“By?” Nandina asked.

“By whomever wants to write it,” Charles said.

“ Who ever,” Irene corrected him.

“Oh, I beg your pardon. How gauche of me. See, this would be a gift for the old codger in the family. His children would contract with us to publish the guy’s memoirs — pay us up front for the printing, and receive this bound leather dummy with his name filled in. On Christmas morning they’d explain that all he has to do is write his recollections down inside it. After that it goes straight to press, easy-peasey.”

He held the book over his head and riffled the pages enticingly.

“What’s to stop the codger from just writing stuff on the pages and letting it rest at that?” I asked him.

“All the better for us,” Charles said. “Then we’ve been paid for a printing job we don’t have to follow through with. It’s strictly non-refundable, you understand.”

I refrained from making one of my Beginner’s Flimflam remarks, but Peggy said, “Oh! His poor children!”

Читать дальше