“Hi, Mimi,” I said.

She arrived next to me, breathless, and gazed down at where the tree had stood. “If that is not the sorriest sight,” she told me.

“Yes, well, it had a good long life, I guess.”

“Nasty old thing,” she said.

“Mimi,” I said, “how long is it since your husband died?”

“Oh, it’s been thirty-three years now. Thirty-four. Can you imagine? I’ve been a widow longer than I’ve been a wife.”

“And did you ever, for instance … feel his presence after he died?”

“No,” she said, but she didn’t seem surprised by the question. “I hoped to, though. I surely hoped to. Sometimes I even spoke out loud to him, in the early years, begging him to show himself. Do you do that with Dr. Rosales?”

“Yes,” I said.

I took a deep breath.

I said, “And every now and then, I almost think she does show herself.”

I sent Mimi a quick sideways glance. I couldn’t gauge her reaction.

“I realize that must sound crazy,” I said. “But maybe she just hates to see me so sad, is how I explain it. She sees that I can’t bear losing her and so she steps in for a moment.”

“Well, that’s just absurd,” Mimi said.

“Oh.”

“You think I wasn’t sad when Dennis died?”

“I didn’t mean—”

“You think I could bear losing him? But I had to, didn’t I. I had to carry on like always, with three half-grown children depending on me for every little thing. Nobody offered me any special consideration.”

“Oh, or me, either!” I said.

But she had already turned to go. She flapped one withered arm dismissively behind her as she stalked back toward the alley.

I asked at work. We were sitting around with a birthday cake — Charles’s — and paper cups of champagne, and Nandina had just stepped into her office to answer her phone, and I was feeling, I suppose, a little emboldened by the champagne. I said, “Let me just ask you all this. Has anyone here ever felt that a loved one was watching over them?”

Peggy looked up from the candles she was plucking out of the cake, and her eyebrows went all tent-shaped with concern. I had expected that, but I’d figured it was worth a bit of Oh-poor-Aaron, because she was just the kind of person who would think her loved ones were watching over her. She didn’t speak, though. Irene said, “You mean a loved one who has died?”

“Right.”

“This is going to sound weird,” Charles said, “but I don’t have any loved ones who have died.”

“Lucky you,” Peggy told him.

“All four of my grandparents passed on long before I was born, and my parents are healthy as horses, knock on wood.”

Ho-hum , was all I could think. People who hadn’t suffered a loss yet struck me as not quite grown up.

Irene said, “My father died in a car wreck back when I was ten. I remember I used to worry that now he might be all-seeing, and he’d see that I liked to shoplift.”

“Ooh, Irene,” Charles said. “You shoplifted?”

“I stole lipsticks from Read’s Drug Store.”

It interested me that Irene imagined the dead might be all-seeing. More than once, since the oak tree fell, I had been visited by the irrational notion that maybe Dorothy knew everything about me now — including some past fantasies having to do with Irene.

“The funny part is,” Irene was saying, “back in those days I didn’t even wear lipstick. And anyhow, I could perfectly well have paid for it. I did get an allowance. I can’t explain what came over me.”

“But did he find out?” I asked.

“Excuse me?”

“Did your father find out you shoplifted?”

“No, Aaron. How could he do that?”

“Oh. No, of course not,” I said.

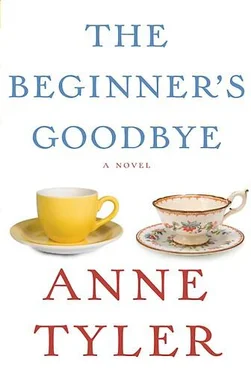

“Sorry!” Nandina caroled, and out she popped from her office. “That was Hastings Burns, Esquire. Remember Hastings Burns, Esquire? The Beginner’s Legal Reference ?”

“ Beginner’s Nitpicking ,” Irene said.

“ Beginner’s Pain in the Butt ,” Charles put in.

I was just glad to have the subject switched before Nandina learned what we were talking about.

· · ·

Then I was walking toward the post office on Deepdene Road and Dorothy was walking beside me. She didn’t “pop up” or anything. She didn’t “materialize.” She’d just been with me all along, somehow, the way in dreams you’ll find yourself with a companion who didn’t arrive but is simply there — no explanation given and none needed.

I avoided looking over at her, because I worried I would scare her off. I did slow my pace, though. If anyone had been watching, they’d have thought I was walking a tightrope, I proceeded so carefully.

In front of the post office, I came to a stop. I didn’t want to go inside, where there would be other people. I turned to face her. Oh, she looked so … Dorothy-like! So normal and clumsy and ordinary, her eyes meeting mine directly, a faint sheen of sweat on her upper lip, her stocky forearms crossing her stomach to hug her satchel close to her body.

I said, “Dorothy, I didn’t push you away. How can you say such a thing? Or I certainly didn’t mean to. Is that what you think I was doing?”

She said, “Oh, well,” and looked off to one side.

“Answer me, Dorothy. Talk to me. Let’s talk about this, can’t we?”

She drew in a breath to speak, I thought, but then it seemed her attention was snagged by something at her feet. It was her shoe; her left shoe was untied. She squatted and began tying it, hunched over in a mounded shape so I couldn’t see her face. I lost patience. “You say I’m pushing you away?” I asked. “You’re the one doing that, damn it!”

She heaved herself up and turned and trudged off, hugging her satchel again. Her orthopedic-looking soles were worn down at the outside edges, and her trouser cuffs were frayed at the bottoms, where she had trod on them. She headed back up Deepdene to Roland Avenue and turned right and I lost sight of her.

You’ll wonder why I didn’t run after her. I didn’t run after her because I was mad at her. Her behavior had been totally unjustified. It had been infuriating.

I kept on standing there long after she had vanished. I no longer had the heart to see to my business at the post office.

Once, we had an author at work who’d written a book of advice for young couples getting married. Mixed Company , it was called. He ended up not signing with us — decided we were too expensive and chose an Internet firm instead — but I’ve never forgotten that title. Mixed Company . I’ll say. It summed up everything that was wrong with the institution of marriage.

“ Here’s a question,” I said to Nate. We were seated at our usual table, waiting for Luke to finish dealing with the salad chef’s nervous breakdown. “Have you ever had a visit from anyone who’s died?”

“Not a visit in person,” Nate said, reaching for the bread basket.

“You’ve had some other kind of visit?”

“No, but my uncle Daniel — actually my great-uncle — I came across his picture once in the paper.”

It seemed to me that Nate might have misunderstood my question, but I didn’t interrupt him. He broke open a biscuit. He said, “They had a photo of these government officials in South America. Argentina? Brazil? They’d been arrested for corruption. And there he was, along with a row of other guys. But in full uniform, this time, with a chestload of medals.”

“Um …”

“It was strange, because I’d definitely seen him in his casket several years before.”

“Really,” I said.

“You couldn’t mistake him, though. Same bent shape to his nose, same hooded look to his eyes. ‘So that’s what you’ve been up to!’ I said.”

Читать дальше