The VW was good, too. He held still as the Unforgettable Thermos, he poured the sacred chai, he helped row the boat during the river scene. The lights reflected his blue, perfect face, filled with concentration. He looked, there on the stage, like a young milk cart in the making, and I was proud and filled with confidence for what he was and what he would become.

I reached for the hand of the woman with half a face, and I whispered into her one ear. “That’s my son,” I said.

KNOW-HOW

I want to tell you the end of the story, the katydids raccoon, and I think I can do so in one seissun, a seissun I’ll call “Know-How.” Because now I know how.

The VW failed to track down the Heart Attack Tree, and so did I. Some roadsongs yield bookmills, and some trips trip and slip and break their Volkswageny necks. In the months after the Volkswagen’s death I stopped writing about Trees, thinking about Trees, believing in Trees altogether. If I saw a Tree on the street or on a lawn, I would shout at it in disbelief and then turn and walk the other way.

I spent most of those first Memory of the Volkswagen weeks by myself, in my home, wearing silence and watching, through the window, the long, slow blink of Northampton — the way the city opened her eyes on me, closed them, kept them closed for a while, and then opened them again. I’d always ask her the same question: “Will you help me?” But of course she didn’t respond. As if she wasn’t aware of my sorrow!

“I’m all alone,” I told her.

The city said nothing.

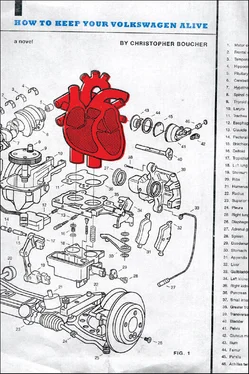

Sometimes, I’d forget the How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive and I’d start driving out to Florence or Amherst just like I had six months earlier. I’d be moving at top speed when I’d awaken to the fact that my son, my car, was dead — that this trip was impossible, just a Memory. Then I’d have a breakdown-in-belief, which involved my stopping suddenly and falling to the ground, often injuring myself and ripping my clothes. Then I’d get up, brush myself off, and walk home.

But if you don’t find the stories, they’ll find you. And that’s exactly what happened to me one Friday a few months after the VW’s death.

By that time, I’d traded in enough of the VW’s parts to be able to afford a used pair of BioLegs, and I’d gone ahead and had the surgery *. The bio’s were slightly too small, and sometimes they really ached, but hey — they were convenient and reliable, and they got me from one chapter to the next.

I was short on time, though, so I was still selling extraneous chapters from the book of power. That day, I’d brought a few stories (“Valve Adjustment,” “A Scanner Darkly,” “Coal Miner’s Daughter”) to the Troubadour — an experimental bookstore in North Hatfield — to see what I could get for them. I’d turned in the chapters at the counter, and I was browsing through the shelves while the owner — a kind vinyl sofa — assessed them. I’d found a few books on the moment and I was skimming through them. Even though the VW was gone, I still had questions. I couldn’t help but wonder, for example, whether Momentism, the belief system, had anything to do with a momentpump . So I was flipping through the beliefs, one by one.

Deep in those dark stacks I felt a tap on my shoulder, and when I turned I saw a tall, thick oak tree hovering over me. He was wearing a disguise — a fake moustache, fake glasses, a baseball hat, a trenchcoat — but even so I knew exactly who he was. I read his eyes and they told me the story. And I could smell the blood on his breath.

I’d always planned for this moment, for the day when I finally met the Tree, and how I’d hurt him in surprising ways — saw his arm off (how I wish I’d had my musical saw with me!), crush his face, poke out his eyes or kick him in the balls. But none of that happened. He put one branch over my mouth, picked me up with another branch and drew me inside his coat, close to his chest. Then he turned and walked towards the exit.

Inside his coat, it was dark as birth. There were stars, and a moon, and it was perfectly quiet. I couldn’t breathe, and I didn’t want to. I observed that I might suffocate, and for a few seconds every word was the same. I met my own Memory, looked into its hollow eyes.

The Tree rushed me out of the store and through the parking lot. When he opened the coat I covered my eyes in the new light. By the time I’d caught my breath and regained my wheres, the Tree was gone — I saw him sprinting down Route 5, the trenchcoat waving open to reveal his thick, barky legs.

I didn’t chase him or call after him — at that moment I didn’t even care about him. I was too stunned by what I saw in front of me. There, parked on a sidestreet about fifty feet away, was an idling Atkin’s Farm. I ran toward it as fast as my bio’s could carry me.

HOW TO KEEP YOUR VOLKSWAGEN ALIVE FOREVER

The night had told me the truth about my son, but lied about my father.

He was sitting inside, heartless, at his table near the scarred window. He was only half-alive. His face was a still lake and his eyes were dirt roads. Through the hole in his chest I could see his lungs, struggling to fill.

“Dad,” I said. “Dad.”

He looked at me lakeishly. It was clear from his eyes that he had no heart.

“Dad,” I said.

“What,” he said. Then he said my name, and put out his hands.

“Stay right there,” I said. “Stay right there, OK?”

“I’m not going anywhere,” he said.

I ran back into the store and spoke to the sofa behind the counter. “Please,” I sang. “I need to buy back some chapters.”

“What chapters?” he said. “Of the power.”

“Which power?”

“The one I just sold you,” I said. “You sold it here ?”

“Remember, I was just in here?”

“When?” he said. “Five minutes ago!” I said.

“No kidding?” he said. “No, I don’t remember that.”

“Literally like five minutes ago.”

“I think I would remember that.” The sofa put his hands on his hips. “Well, I’ll go check.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“Let me just find my glasses,” the sofa said, wobbling into the back room.

Wires in my mind began to fray, to snap. “Please hurry,” I said. “A man’s life depends upon it.”

Then I heard the sofa’s voice: “Was it a book about sand?”

“No — it was about—”

“Was it a songbook?”

“It was stories from a book about Volkswagens ,” I shouted back.

• • •

I sprinted out of the store and back to the farm. I sat down beside my Dad at the corner table and I held out a story — a quickloom about a makeup named Emily.

My father looked at the pages. “That’s supposed to save me?”

“It’ll buy us a few more minutes,” I said.

He took the story and began to read.

I got behind the deli counter of the farm, fired it up, shifted it into gear and sped it back to Northampton. There wasn’t much money. I raced up the hill to the Crescent Street Apartments, ran inside, then coaled back into the farm and drove it out onto Route 5 and south, towards Springfield and the BayState Hospital.

Twenty minutes later I pulled into the hospital parking lot, parked the farm and ran into the emergency room. When the hospital recognized me his eyes became dry, dour stalks. “You,” he hissed. “How dare you show your noface here.”

“Listen,” I said. I bent over to catch my breath.

“After singing the song that killed my son? I should have you removed—”

“We found the farm,” I said. “And we found my father.”

All his rooms were dark. “Good for you,” he nickeled.

Читать дальше