A few days after that, I was carrying the VW to Florence when I heard a clang on the sidewalk and I noticed that one of the VW’s wings had fallen off. I stopped walking, put the VW down and picked up the wing. By now it was all rusted and it smelled terrible, like forgotten words.

Something changed for me as I stood there on the sidewalk with that wing in my hand. It was at that moment, I think, that I surrendered. This procedure wasn’t working — the book of power was wrong again. There was nothing more that I could do. The VW couldn’t be resurrected and he couldn’t be jumpstarted — no story on earth could save him. The VW was dead.

• • •

That night, I wrote one more story for the VW — a story of apology. I was the main character and the plot was, I was very sorry. Sorry for not taking better care of him. Sorry for ignoring the signs of his failing health. Sorry for writing the book of power, which had been wrong at every turn.

I wasn’t listening , I wrote. I thought I was, but I wasn’t. I thought the stories would save you. That they would save my father. I thought they were worth so much more .

And I wasted so much time! Time I would do anything to have back again .

No VeggieCar will ever replace you , I wrote. All of my roadtrips will be Volkswagen roadtrips .

Sometime that night, while I was writing that story, the Memory of the Volkswagen sat down at the kitchen table.

“How’d you get in here?” I said.

“Easy. I’m a Memory,” said the Memory of the Volkswagen.

“Please go away,” I told it.

“I’m not going anywhere, Dad,” the Memory of the Volkswagen said.

ENGINE OVERHAUL

The next day I brought the Volkswagen back to the swordfish. I wouldn’t look the fish in the face when I walked in with the car. All I said was, “How much again for the headlights?”

The swordfish crossed his fins. “Twenty-five,” he said.

“I thought you said thirty,” I said.

“They weren’t so dusked then,” he said.

I looked into his whiskery face.

“Twenty-eight,” he said.

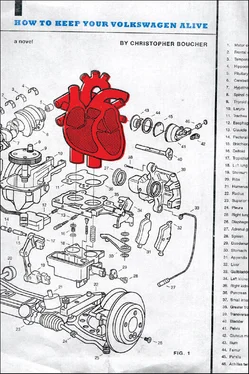

That day I sold that swordfish the memory coil, some of the morning cables, the passenger seat, the steering wheel, the dashboard and two transmissions. And whenever I needed time, I’d go back there and sell something else. Over the next year I sold him all of the transmissions plus the sound stage, the differential, and dozens of other parts. Some parts weren’t worth saving (the fin, the second engine), so I put them in the dumpster behind the Crescent Street apartments. Other parts I stored in the VW’s room; they’re probably still there.

Every time I went to see the swordfish he asked about the engineheart. I always declined to sell it. He offered me fifty-five for it once, then sixty another time. I shook my head and said, “The heart still beats.”

“Seventy,” he said.

“The heart of the Volkswagen is not for sale,” I said.

“Seventy-five hours,” he said.

“Not for all the time in Northampton,” I told him.

BUTTERFLY VALVE

These days, all I have left are these spare waltzes, sitting around and fermenting in jars. Like these over here, about the VW’s experiences as an actor. Have I told you any of these yet?

I remember one time in particular, when they were holding auditions for the air-cooled play, Emily Dickinson Rides Again . The three of us — the Volkswagen, the Memory of My Father and me — went down to the Academy of Music one Saturday morning so the Volkswagen could read for a part.

When we got there we saw that the hallway outside the audition room was filled with other parents and children — baby lamps, small air conditioners, toddlers sitting cross-legged on the floor — but I didn’t see any other Volkswagens. A spider came by and I gave her the Volkswagen’s name. Then the Memory of My Father stepped forward and asked her to write his name down as well.

“What are you doing?” I said to him.

“Auditioning,” he said.

“You have a role already — you’re the Memory of My Father.”

“I can play two parts at once,” he said to me. “So can you, if you want to.”

“But you’re the Memory of My Father, which means that you’re going to have to do your best to look and act like my father ,” I told him. “He would never audition for a play.”

“There’s a role in this play for the Memory of Mount Holyoke,” the Memory of My Father said, and he flexed his bicep muscles. “And look — look at these guns. Are these things mountain muscles or what?”

“We’ve got a whole book ahead of us—” I began, but the Memory of My Father flickered away, which he sometimes did when he didn’t want to hear it from me. A minute later he reappeared in a far corner of the room.

In the end, I decided to audition too. I used to act as a kid, and I figured that I’d be making frequent trips to the Academy anyway if the VW was cast. An hour or so after we arrived, I was called into the audition room and told to take off my clothes. As I stood there, a man with a ponytail came in with two women and they sat down at the table. “Good morning,” the man said.

“Hi,” I said.

He looked at his clipboard. “That is a very interesting name,” he said.

“Thank you,” I said.

He sounded it out slowly: __________________.

“It’s French Canadian,” I told him.

Over the next few minutes the three of them made various requests: They gave me a sandwich and asked to see me eat it, they asked how I felt about fences and they told me to read a few lines from the character named Tom, who was a General in the play.

“Tantamount Price !” I boomed, stretching my arms up to the sky. “Let go of my wallet, and let me seep into the night!”

I thought it went well, and when I spoke to the Memory of My Father he said he thought his audition went fine, too. But in the end, neither of us got a part. Only the VW was cast, and even he didn’t get the part that he wanted; he auditioned for the role of the Volkswagen, but was cast as the Unforgettable Thermos instead.

After the parts were announced, the VW cascaded the director. “The Unforgettable Thermos?” he said.

“Of course,” the director said.

“I read for the part of the Volkswagen. ”

“You did, I know,” said the director. “And you were really very fine — you have a lot of talent.”

“Then why didn’t I get that part? I was that Volkswagen in there,” said the VW.

“But you are so right for the Unforgettable Thermos,” said the director. “The minute I heard your voice I could tell.”

“ I’m the Volkswagen, though,” said the VW. “This is my story.”

“You’re a Volkswagen.”

“Who’s playing the part, then?”

“The podium’s going to play the Volkswagen,” said the director, and he pointed across the room at a podium, leaning against the wall and talking to a woman.

“You’ve got to be kidding,” said the VW.

• • •

A few weeks later I went to see the play. I took the Memory of My Father and a half-faced woman who I was dating at the time. She was a real beauty, but we only dated for a short time because she fell in love with a pharmacy and left me for him. But we weren’t there yet; things were still good.

The production was wonderful. The podium did a great job; he was the best Volkswagen I’d ever seen. His facial expression when looking into the dream, seeing Emily Dickinson for the first time? For me it held a real moment of growth, when a child realizes there are walls in life, places we cannot go. There is this world and there are other worlds, and pain blooms when we can see into those places, feel the need to get to them, and then find ourselves unable to, trapped in the here and the now.

Читать дальше