Later that day, the VW and I went down to my Dad’s workbench in the basement of the Crescent Street house and we tried to loosen the lock. I let the VW try first — he tried to pick the lock with a paperclip, and then he took a tiny flathead screwdriver and tried to pry the catch.

But I grew impatient, and after ten minutes or so I went and grabbed a crowbar. “Give me that thing,” I told him.

“Don’t use that — you’re going to snap the latch right off,” the VW said.

“I won’t — I’ll be careful.”

“Dad—”

“Give it,” I said, and I took the box from him. I stuck the prybar against the latch and turned it, which created a little gap between the two halves. I heard moans inside.

“What’s that sound?” the VW said.

The latch wouldn’t give. I pushed hard on the crowbar once, twice.

“Careful—”

“I’m being careful,” I said, and pushed again, but this time the wood cracked.

We both stared at what I’d done.

“Did I tell you?” the VW said.

I’d pried the lock right out of the wood, ruined the lid. I said a custom-made swear.

“Didn’t I tell you not to use the crowbar?” the VW said.

“Just don’t tell the Memory of My Father,” I said.

“Like he won’t know.”

“He won’t know, not if you don’t tell him,” I said. “I’m sick of you two conspiring against me.”

“What?” the VW said.

“Everyone in this engine is conspiring against me,” I said.

“Dad,” the VW said. His face was plaid. “Do you really think that?”

I heard a soft boom inside the box, and then small voices.

“Are you going to open that thing, or what?” the VW said.

“I’m getting to it,” I told him. “Don’t push me — I’ll open it when I’m goddamn good and ready.”

“Alright, alright,” the VW said.

I slowly opened the lid and we both peered inside. Immediately I knew what we were looking at.

“It’s a war ,” I whispered.

It was night inside the box — the stars and the moon hung below me. Tiny men the size of eyelashes were running across a field. Then, the crack and flash of a bomb. All of the running men stopped and froze, then dropped back behind a hill. Gunshots came, and a new team of men surrounded them.

All of the soldiers were of one mind. You could see it in their faces as they aimed and fired, ran and hid, destroyed the hearts of others, lost their legs and eyes and either a) died or b) did not die.

The VW pulled back from the box and his face shawled. “What are they doing?” he said.

I was upset, of course. What was this war about ? And what was I supposed to do with it?

“They’re fighting,” I said.

“What for?” the VW said.

“It’s a disagreement of some kind.”

“Over what?”

“I don’t know the specifics,” I told him. “It could be anything.”

The VW didn’t say anything. He stared into the box, at the dead on the field, and then he looked down at his shoes. “Can I go to my room?”

I felt guilty all of a sudden. “Sure you can, buddy,” I said.

I placed the lid back on the box and I called the Memory of My Father, and he came over an hour later. He sat down on a stool in front of the box. “Open it,” I told him.

“What’d you do here?” he said, pointing to the lid.

“I don’t know how that happened,” I said.

“You tried to pry it open, didn’t you?” the Memory of My Father said.

“I didn’t touch it — the VW must have done that,” I told him.

• • •

We kept the war going through the fall. The Memory of My Father left the box in the basement, and every few days I would check on it and see what was happening. Many lives were lost. The sun rose and fell. I looked to see if there might be any end in sight, but I didn’t have the whole thing — this box was apparently only one piece of a much larger conflict — so I never knew who was who and whether one side was making more progress than the other.

One Sunday that winter, the Memory of My Father met an antiques collector at an estate sale. He told this man about the box and the designs on the front, and the collector said he’d like to see it. The Memory of My Father called me that afternoon and told me to clear out the war so that he could show the box to the collector.

“How am I supposed to do that?” I asked.

“You’re a big boy, you can figure it out,” the Memory of My Father said. “Just scoop it out.”

Something inside me was sad. “Did you tell him about the lock?”

“Bah,” the Memory of My Father said. “He won’t even notice it.”

I thought long and hard about how to get rid of the war — I didn’t want to just pour it out. Instead, I put the box in the freezer, thinking that all of the soldiers would freeze and die, and then I could dump the whole thing into the trash — hills and bunkers and bodies and all.

But somehow the soldiers survived the cold. I opened the box after two days in the freezer and I saw a division dressed in fur, marching stiffly along a perimeter. By this point I was using a magnifying glass (which I borrowed from my son’s science kit) to see closer, and I could see every face as individual and unique. I saw two men huddled together for warmth and another a few feet away, writing a letter. I snatched it from his hand and read it.

Things get worse all the time. This cold front is upon us and every day we lose more men. My Sergeant says that we will never give up, never die, but if I can’t get warm soon I don’t think I’ll make it .

I think back to home. Remember the shower day? That Tuesday before the concert? I think of you and how warm that was .

God, my hands. I can’t hold the pen. Have to go. I’ll write again tonight .

Love

I brought the box with me when I went home that night for dinner and I held it out to the Memory of My Father. “The war’s still in there,” I told him.

“What?” he said. “I told you to clear it out.”

“I tried to freeze them but it didn’t work.”

“Just get them out of there, what the fuck!” the Memory of My Father said. Then he took the box under his arm and went outside. The late afternoon sun was a piece of candy. The Memory of My Father turned on the hose and opened the box. All of the fighting stopped and the soldiers looked up into their sky, past their sun and into the Memory of My Father’s face. He sprayed the inside hard, until all the dead bodies and the hills and streams and stars and moon were pushed out onto the pavement, and within minutes the box was completely empty. With his holy hose, The Memory of My Father forced them down the driveway and towards the gutter at the curb.

The antiques collector didn’t buy the box — he was upset when he saw that it had a broken lock — and so the Memory of My Father brought it home and stored it in his garage.

A few years later I found the box again, dusty and stashed in a corner. I opened it up and peered inside. I saw six or seven men huddled around a fire. I think there was a crude map of some sort at their feet. It looked to me as if they were making plans.

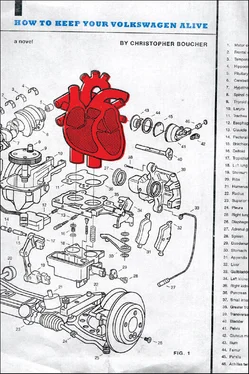

ENGINE STOPS OR WON’T START

There are several reasons why your Volkswagen might stall, stop or not start. The most common culprits are the fuel injection system (pump, condenser)or a glitch in the timing. But don’t overlook the possibility that it might also be a malfunctioning control unit—a much more serious problem.

MECHANICS

First, there may be a problem with the ignition, “How to Use This Book.” Have you reviewed it to make sure that it reads at the right speed?

Читать дальше