I went to the funeral, stood in the last pew at the Smith College Chapel, watched the hospital’s father — the distinguished BayState Hospital, from Springfield — shake with grief in the front row, his old windows weeping into his white beard. I stared at the giant, hospital-shaped casket, my mind dividing itself into parts. Which sections should I keep? And which sections must go?

I’ll keep this and this . To hell with the rest of it.

Cooley-Dickinson’s sister, a paint store in New Haven, gave the eulogy. “When I think back to Cody,” she said, grimacing through tears, “I just try to forget the last years, these last croons. I think Cody would want that. The Wheel might regard him as the victim of a Tree, but I remember the Cody who finished hospital school a year early; the Cody who, before this whole thing started, loved to draw comics, and was excited about the upcoming release of his first comic book series, STAT. ”

Then the paint store coda’d into a southern maine — a plastic review about the hospital’s comic book, which was set, fittingly, in a hospital. She described the first issue, a funny thin side about a dying basketball which had the audience craughing.

I just kept thinking, this hospital was an artist . A brother, a son. And look what I/the tree had done to him.

I accompanied the funeral party to the cemetery and watched them lay the hospital into the ground. After the service, I approached the old hospital and offered him my hand. I looked into his old rooms and started to tell him who I was, who my father was, but he put up his hand and said, “I knew who you were, Mr. _____, the minute you walked into the church.”

“I just wanted to say how sorry—”

“No,” he said, his voice trembling. “Don’t give me your sorries. You tell them to my son. ”

I was silent.

“You go there,” he said, pointing to the giant hole in the earth, “and you tell Cody that you’re sorry.”

I stammered a response.

“Mr. _____,” the old hospital said, leaning over me. “Why these stories? Why this one, in particular?”

By then other mourners had stopped to hear our discussion. “I–I don’t follow.”

“You don’t follow ? How about, for once, a happy tune? How about, a young promising hospital gets renovated, or gets married, or—”

“You sound like my son,” I said. “This is what he tells me, too.”

“He’s right,” the old hospital said. “You should listen to him.”

“Sir,” I said, my voice just a note above a whisper. “These stories chose me. They chose me.”

“Then ignore them!”

“Ignore them?”

“People’s lives are at stake here!” he coaled.

“I’ve tried . If it were only that simple.”

“Then run. Run away. Go somewhere where these stories can’t find you.”

“I’ve tried that, too,” I said. “But they’re faster. They find me every time.

“I’ve tried everything ,” I told him.

I WOULD DIE FOR YOU

I’m thinking back, going back in my mind, to that Sunday in the fall of 2004, when the Memory of My Father and I went to the flee bee — the Old Hadlee Flea Market, held every week on a small farm on Route 47—and he bought a small war in a beautiful little wooden trinket box.

Was that in ’04—so long ago already?

Yes, I think it was, because it was the same day that I bought the corpse of an old accordion who’d gotten in a bar fight and been stabbed and killed. I bought it from a moustached truck who was selling it for two and a half hours. “No guarantees,” he said as I handed over the time. He put the coffin in my arms; the instrument’s bellows were stiff, its keys cold and grey.

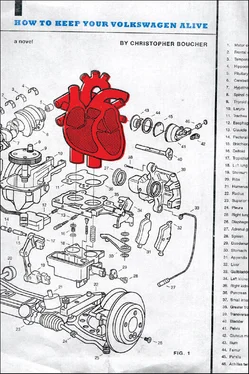

My hope, though, was that I might be able to fix the accordion and convince the VW to take lessons on it. I’d always loved the accordion, and so had my father. I brought the musicorpse home and began working on it — I opened its skin at the seam, fed it fluids and nutrients intravenously, repaired its organs with epoxy and c-clamps, replaced two of its buttons, sewed its wounds and reattached its skin — and a few days later it opened its eyes and looked into my face.

“Oh god thank you,” he said, weeping.

But then the VW refused to play. That night — the night the accordion was resurrected — I put on some Cajun music for the VW to listen to, and he heard two notes and said that it was the least cool thing he’d ever heard.

“You don’t like this stuff?” I said.

“People actually listen to this?” the VW said.

“It’s nice — it’s folky, happy,” I said.

“It’s a rose bush making fart sounds with its elbow,” the VW said.

So I had to kill the accordion all over again. The next morning, I set up a noose and a small stool in the front yard. I had the instrument stand in place on the stool while I slipped the rope around his neck.

He flailed his tiny, keyed hands. “Please, no!” he begged.

“My son doesn’t want you,” I told him. “I really thought he would.”

“I need to live!” the accordion said.

“But for what purpose?” I reasoned with him. “Who will play you?”

I could see his mind working. He stammered for an answer, but my job was clear and I did what needed to be done: I stepped back and kicked out the stool. The noose tightened. The accordion’s eyes went wide. He coughed—”Gack! god — Gack!”—and then his hands fell and his head slumped forward.

I kept him hanging there for a week, as a warning to other instruments. A few days later I was sitting by the window and I saw a French horn walking past on the sidewalk stop cold when he noticed the re-killed and hung accordion. His face was filled with fear.

At the end of the week I took the accordion down, laid him in his coffin and buried him. I wonder whether I’ll see him again.

But I was talking about the trinket box with the war inside, the one the Memory of My Father bought at the flee bee that day. As I said, he didn’t mean to buy the war; he was just interested in the box, which was made of spruce and had some very interesting designs carved in the lid. As near as I could tell, the woodcuts told a story — a story about a chariot in the Old West. There was one scene with the chariot in a duel, his wide-brimmed hat cocked back and his hand hovering over his holster.

I was there when the Memory of My Father bought it, from a young girl who was watching the table while her mother went for coffee. He paid only twenty minutes for it, because the box was locked and the girl said the key had been lost. The Memory of My Father bought it and tucked it under his arm and the two of us walked proudly back to the car — he with his storybox, me with my coffined accordion.

It wasn’t until about a half an hour later, as we were driving home, that I picked up the box to study the scenes and heard noises coming from inside it. I put the box to my ear and I could hear booms and crashes.

I held the box out to the Memory of My Father, who was steering with one hand and holding a jelly donut with the other. “Listen to this,” I said. I held it to his ear.

“I just hear shifting,” he said.

“There’s something happening inside this box,” I declared. I tried again to open it, but couldn’t. “I’m going to open this thing up and see what’s inside it.”

“You do that and you’re going to fuck up the lock, and it won’t be worth anything,” the Memory of My Father said. “Just leave it be, _____.”

“I won’t fuck up a thing,” I said. “I’ll be careful.”

The Memory of My Father shook his head and bit into his donut.

Читать дальше