I unlocked the door but had to push hard to open it even a crack. As soon as I did I could smell the decomposing books inside.

I’ve always wondered: Why do so many things have to die in this book, and why is there always that smell ?

The VW held his nose. “Why do so many things die in this book, and why is there always that same smell ?” he said.

“Just help me push, will you?”

He did; we pressed against the door until we could open it enough to squeeze inside.

As a child, this library had been a real home for me. I remember running through the rooms as a boy with my brother and the distant Promise of the VW, getting drunk off the books as a teenager — hiding among the shelves and pressing those secret words against my eyes.

I realize now: I couldn’t agree after that. How could I, after all the mechanical work I’d done on my own mind — the carving and slicing and reshaping? I’d liquidated tissue, pulled some wires out and used them to reconnect things in new ways. I’d told no one, either; it was secret surgery.

I remember, too, all the time I spent with the Two Sides of My Mother — sitting at the desk with One Side as she checked out the books, helping the Other Side in the basement as she operated on those volumes that were sick or dying (watching her steady hands as she made tiny incisions in the books’ skin, the wordoil that sprang onto her arms).

Now this place was cold and dark, empty as a kite. The VW and I walked the halls on the first floor and then climbed up to the second, checking the pulses of the books strewn across the shelves and the hardwood floors. All I wanted — all that I had ever wanted — was to find something alive, but that wasn’t going to happen here. This place was a tomb.

In the midst of checking the last room for survivors, I turned around and realized that the VW was no longer behind me. I called his name, and when he didn’t respond I retraced my steps. At first I was upset — he was always wandering off, getting lost! — but that feeling disappeared when I saw where he was. I found him standing at the top of the second floor balcony, his hands wrapped around the banister, his head hung and his eyes staring down at the shelves of dead magazines on the lower level. I could tell when I saw him how overwhelmed he was — his face was an underground tunnel to free the slaves.

I stood next to him without saying anything. Then I said, “I think they’re all dead.”

“Why,” he said, without looking at me.

“I just checked all the rooms,” I said softly.

“But why did it happen?” he said. “Why did they die?”

I felt almost like a real father. “I don’t know,” I said. “I used to ask that same—”

“ Everything has to die, doesn’t it,” the VW said. “You, and me too.” His eyes were dim — either on a low setting or else turned off completely.

I wasn’t sure how to respond to that, but then I thought of something the Other Side of My Mother used to tell me, an old twig I’d long since stepped on and snapped. “It’s only the body that dies, VW,” I said. “The soul,” I said, etcetera.

“I don’t want to die,” he whispered.

“Kiddo,” I said. I picked him up and chucked him on the chin. “These books were old. They were ready to die.”

The VW scanned the magazines, some of whom had leapt to the floor and died with their arms or legs outstretched. “They were?”

“Sure,” I lied. “Look at their faces.”

“But I’m young and new,” the VW said. His eyes brightened. “Look at my face.”

“Right—”

“And you have the tools , right? To repair me if anything goes wrong?”

“Most of them,” I said.

The VW’s face grew stern. “And you know what you’re doing?”

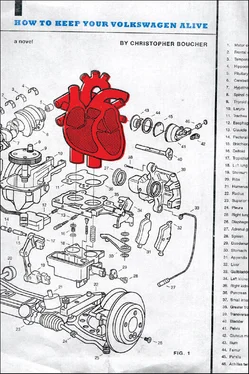

“Absolutely I do — I’m writing a book of power on Volkswagens,” I said.

“So why can’t you just make sure?”

“To keep writing?”

“To keep me going . To make sure I don’t break down or ever get old or die.”

“Well — I’m — I mean, that’s why I spend so much time maintaining you, buddy. To make sure you’re running right.”

“You promise?” the VW said. His face was now a holiday, a free giveaway.

“Promise what?”

“Promise that I won’t die?”

I didn’t say anything. My mind stalled. I hated the idea that the VW was worrying about this now . He was just a child, for god’s sake.

“You promise, Dad?”

The high-beams of light in those eyes — I would have said anything to keep them shining.

IV. HOW TO DRIVE A VOLKSWAGEN

TRANSMISSION

Transmission from whom , though?

From the Chest of Drawers, my friend and former professor, who taught Religious Studies at Northampton University. We used to go hiking up Summit Mountain in Hadley. And if we didn’t, I always wished that we would have — that I’d really had a friend named the Chest of Drawers, that there really was such a thing as Summit Mountain (with a museum inside which told stories of the old cable-car hotel that used to stand in its place, and a monument to a group of soldiers who’d crashed their plane into the mountains), that there was such a thing as Hadley, or America, or me.

When the VW was old enough I took him with us, but it was always problematic when I did. When he was younger the VW couldn’t keep up, and when he was older he was ill all the time, never strong enough for the hike. He would have to stop and rest, or I’d look back and find him leaning against a tree. Once, in his last year of life, I remember he stopped halfway up the trail, knelt down by a brook and vomited black, chunky oil into the running water.

But what was I supposed to do? I was a single father to a Volkswagen — I couldn’t just leave him in the parking lot by himself. So the Chest and I made do; sometimes we’d slow our pace down so that he could keep up, and othertimes I’d carry him on my shoulders.

The clearest transmission that I can remember, in fact, happened late in the summer of ’03, on one of our first hikes with the Volkswagen. I hiked the first half-mile with the car on my shoulders, but then he grew rambunctious and started asking to be put down. When I said no he started banging his heels against my chest.

I told him to stop it. “I’m only doing this because I don’t want you falling behind,” I said.

“I won’t ,” he said.

“You say that now,” I said, “but I know you, kiddo. You’ll wander off.”

“_____,” said the Chest.

“He gets distracted very easily,” I told the Chest. “Maybe on the way down, VW. OK?”

“We’ll just keep an eye on him,” the Chest said.

“Yeah! You’ll keep an eye on me,” the VW said.

I slowed down and leaned in close to the Chest. “But what if we lose him and the mountain changes?” I whispered to him.

“What do you mean?” the Chest of Drawers said.

What did I mean ? This was in mid-September; the leaves had suffered and were now lying dead on the trails. Even so, you had to keep watch over this mountain, like all mountains, at all times. You didn’t want to give it a chance to change its mind — to transform into a fjord or a roller rink. Such shifts made hiking (not to mention booking! How can I describe something if I don’t know what it is?) almost impossible.

The key was keeping it straight in your own mind. It was September. The leaves had suffered and were lying dead on the trails.

“We just have to keep a close eye on it,” I told the Chest.

“I will, I told you,” the Chest said.

“The key is keeping it straight in our minds,” I said.

Читать дальше