“Listen,” I said. “None of this is very complicated.”

“Not complicated !” the ratchet said.

“I’m a single parent trying to raise my son — that’s all.”

“A car that runs on stories !” shouted the ratchet.

“Harold, let’s relax — take a breath. OK?” the therapist said to him. The ratchet leaned back and closed his eyes and the therapist turned to me. “Mr._____,” he said. “I’d like you to tell me, if you could, about your Memories of the One Side of Your Mother.”

Soon I understood what was happening. This, again, again , was about me — about my favorite teams, my defensive plays. “Look,” I said. I pointed to the ratchet. “His condition—”

“Interesting word,” the therapist said.

“Yes, condition ,” I said. “His condition has nothing to do with me.”

The therapist reached his hand out towards me. “I don’t know that I’m thinking so much about Harold at the moment as I am you.”

“I’m not the one in need of help.”

“I don’t know that I agree with that, either,” the therapist said.

I stood up. “You think you can figure out how I work?”

The therapist gestured towards my chair. “Try me,” he said.

I laughed. “Not a chance ,” I said. “You’d be frightened. You’d tell me I’m making it up — that it’s a fiction . And I don’t want to hear that from one more person.”

“This is all beginning to make sense to me,” the therapist said.

“There is nothing in the world that you can do to fix me,” I told him.

LIVE ART

The Memory of My Father mourned for my father in his way, the Two Sides of My Mother in theirs. In the days after the attack, the Two Sides locked themselves inside their home in Longmeadow, holding each other and smoking their fingers as the grass grew high around them and my father’s orphaned junk wrestled and moaned in the garage.

Down the street, meanwhile, the poor Storrs Library — where the Two Sides of My Mother had worked — grew faint with abandon. For as long as I could remember, the Two Sides had double-handedly run the Library, One Side working the desk and the Other Side repairing books in the basement. Now the books were starved and silent and the double doors stayed locked. Over a period of six weeks, all of the books crawled off the shelves and shuffled over to the windows and doors where they died in piles, their spines broken and their pages stiff.

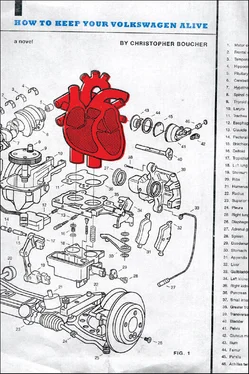

I didn’t know this was happening, of course; I was too busy at the time trying to deal with my own results — a newborn son, a girlfriend who couldn’t bear to stay. From the very beginning I was interested in how the Volkswagen worked, which part was which, but the Lady from the Land of the Beans just wanted him healthy and running.

Even in the first few months after his birth, when she was still in Northampton and we were trying to raise him together, I could tell that she was trailing on the decisions we’d made. Without a manual to work from, she and I had to figure out the procedures ourselves. And it was difficult, because we’d open the rear lid and see something different every time — once, an old man with a hat made of newspaper pedaling his bicycle down a sidewalk that wove through the cables, past the generator and towards the clutch. Sometimes the morning cables were clear and other times they weren’t.

Eventually the Lady from the Land of the Beans became overwhelmed by all this — by the mysteries of this machine, part me and part her, that she had no idea how to fix or treat. One morning, after opening the engine compartment and discovering a thick green forest — vines wrapped around the coils, birds perched on the transmission — she stood up and ran her hands through her hair. “What is this?” she said.

I was testing a patch of moss. “What do you mean?” I said.

“What?” the VW said. “Do you see something?”

“I don’t—” She paced around the VW’s bedroom. “Do you recognize anything here?” she whispered.

“This appears to be peat,” I said.

She was quiet.

“But that, over there. That’s ‘One More Night,’ I think,” I said.

“_____,” she said. She pulled me up and we stepped back so the VW couldn’t hear us. “He’s nothing like any car I’ve ever seen,” she said.

“What are you guys doing?” the VW said.

“That’s because he’s ours ,” I said warmly, and I took her hand.

She didn’t say anything, but she looked down at her hand — the one I held — as it if was something she might detach and leave if she could. I didn’t know at the time what that look meant, but soon enough I came to understand it as a promise.

A few weeks later, I took the VW out for a practice drive one afternoon and when I came home the Lady from the Land of the Beans was gone. I searched the house for her, then went outside. Our half-collapsed VeggieCar was gone, too.

I came back inside and asked the VW if he knew where she was. He shook his head and looked at his wheels, but his headlights were filled with condensation. I picked him up and looked at him eye level. “VW,” I said. “Where did your mother go?”

The VW’s eyes held actual pity for me. “She went home,” he said.

I tried to laugh. “We are home,” I said.

He shook his head. “Not for Mom.”

“What do you mean?” I said.

He looked down at the floor.

“She went back to her home? To the Land of the Beans?”

The VW didn’t say anything.

“You let her do that?” I said. “You let her go?”

“She said she had to, Dad. She couldn’t stay here anymore.”

“Why not?” I asked, my voice quivering. “What did she say?”

He didn’t say anything else.

“You tell me what she said,” I pleaded.

I maytagged at the kitchen table and the VW sat down next to me and leaned against me. I kept saying, “She loved me. She loved me.”

My son whispered, “No. No.”

It was a few days later that I went home and found the Two Sides of My Mother sitting side by side on the love seat in the living room. They were dressed in black and the room was filled with fingersmoke so thick I couldn’t see a word.

The VW, meanwhile, had gone outside to help the Memory of My Father clean up the patio. I remember watching them through the window as they loaded my father’s Invisible Pickup Truck with items to take to the town dump. My father, had he been alive, would have hated it — he saw good and promise in each item that his Memory now threw away — the two-wheeled stroller (which he would have made into a wheelbarrow), the seatless bench (which he would have fixed), the neon beer signs.

I tried to make the Two Sides of My Mother feel better by commenting that it’d be nice to have more space on the patio, that we could plan a meal or a party out there now, but they weren’t saying anything. They just stared past the patio and into my father’s garden, where my father used to spend a lot of his day and where a pack of deer were now praying — deer prayers for the dead, I assumed.

After sitting with the Two Sides for an hour or so I remembered that it was Thursday, normally a work day for them, and it occurred to me that I hadn’t heard about Storrs in weeks. “Hey Mom,” I said. “What’s happening with the library?”

I had to ask the question several times. They were so lost in the fog of death that I think it was hard for them to even hear my voice. But finally the Other Side of My Mother turned to me and asked, “ What library, honey?”

It was less than a mile away, so the VW and I walked over. As we approached it, I could see that the old colonial building was now lying on its side and that the parking lot had now turned into a southwestern desert, complete with cacti and unbearable sun.

Читать дальше