At the end of the year, when final exams came, we learned that 34 had hit the bull’s-eye with his predictions. Four classmates had jumped ship early (including 38), and of the forty-one who remained, forty of us passed. The only one who didn’t pass was, once again, 34.

On the last day of classes we went over to talk to him, to console him. He was sad, of course, but he didn’t seem beside himself. “I was expecting it,” he said. “I’m really bad at studying. Maybe things will be better for me at a different school. They say that sometimes you have to just step aside. I think this is the moment to step aside.”

It hurt all of us to lose 34. His abrupt departure was, for us, an injustice. But then we saw him again the next year, falling in line with the seventh graders on the first day of class. The school didn’t allow students to repeat a grade twice, but for 34 they had, for some reason, made an exception. Many students claimed that it was unfair, that 34 had gotten help from friends in high places. But most of us thought it was good that he stayed — even though we were surprised that he would want to go through that experience a third time.

I went over to talk to him that same day. I tried to be friendly, and he was cordial too. He looked thinner, and you could really see the age difference between him and his new classmates. “I’m not 34 anymore,” he told me finally, in that that solemn tone that by then I knew well. “I appreciate that you’re asking about me, but 34 doesn’t exist anymore,” he told me. “Now I’m 29, and I have to get used to my new reality. I’d rather be part of my new class and make new friends. It’s not healthy to get stuck in the past.”

I guess he was right. Every once in a while we’d see him from afar, hanging out with his new classmates or talking with those same teachers who had failed him the year before. I think that time he finally managed to pass the class, but I don’t know if he stayed at the school much longer. Little by little, we lost track of him.

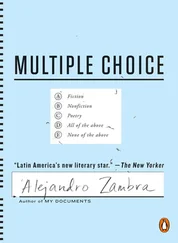

2

One winter afternoon, when they came back from gym class, they found the following message written on the board:

Augusto Pinochet is:

a) a motherfucker

b) a son of a bitch

c) an imbecile

d) a piece of shit

e) all of the above

And underneath it said:

IOP

They were going to erase it, but there was no time, because right then Villagra, the Natural Sciences teacher, entered the room. There was a nervous murmur and some timid laughter, and then absolute silence — the silence that always accompanied Villagra’s classes. Villagra looked at the board for a few long minutes, his back to the students. That writing, with its firm strokes and perfect calligraphy, was not that of a twelve-year-old boy. Moreover, it wasn’t very common for seventh graders to be members of the IOP, the Institutional Oppositional Party.

With the same gravity, the same theatricality as always, Villagra went to the door and looked out to make sure he wasn’t being spied on. Then he picked up the eraser and slowly started to erase the options one by one, but before he got to the last one, “all of the above,” he stopped to brush away the chalk dust that had fallen onto his jacket, and he let out a cough that resounded exaggeratedly. Then, from the last row, Vergara — better known to his classmates as Verga-rara —asked if the correct answer was e). Villagra looked at the ceiling as if searching for inspiration, and his face really did take on an expression of enlightenment. “The question is poorly designed,” he said. He explained that options a) and b) were practically identical, as were c) and d), so it was obvious, by default, that the answer was e).

“So the right answer is ‘all of the above’?” asked González Reyes.

“As I said, it is the correct answer by default. Open your books to page 80, please.”

“Aaaaahhhhhh,” said the boys.

“But, sir, what do you think of Pinochet?” insisted a different González, González Torres (there were six boys named González in the class).

“That doesn’t matter,” he said, serenely and decisively. “I’m the Natural Sciences teacher. I don’t talk about politics.”

3

I remember the cramp in my right hand, after history class, because Godoy dictated for the entire two hours. He taught us Athenic democracy by dictating the way you dictate in a dictatorship.

I remember Lavoisier’s Law, but I remember the law of the jungle much better.

I remember Aguayo saying that “in Chile, people are lazy, they don’t want to work; Chile is a country full of opportunities.”

I remember Aguayo failing us, but offering make-up classes with his daughter, who was beautiful, but whom we didn’t like, because in her face we recognized the dog-like face of her father.

***

I remember Veragua wearing white socks to school and Aguayo telling him: “You are trash.”

I remember Veragua’s hair, and his big green eyes that filled with tears as he looked at the ground, in silence, humiliated. He never showed up at school again.

I remember Venegas, the head teacher, telling us the following Monday: “Veragua’s parents withdrew him. He couldn’t hack it.”

I remember Elizabeth Azócar teaching us to write during the final hours of each Friday. I was in love with Elizabeth Azócar.

I remember Rodrigo Martínez Gallegos, and Hugo Puebla, and Álvaro Tabilo.

I remember Gonzalo Mario Cordero Lafferte, who used to tell jokes during our free hours. If any teachers happened to walk by, he would pretend we were studying French: la pipe, la table, la voiture .

***

I remember that we never complained. How stupid, to complain — we had to bear it all like men. But the idea of manliness was confused: sometimes it meant bravery, other times indolence.

I remember when someone stole the money I was carrying so I could make the optional annual payment at the Parents’ Center.

Later I found out who stole it, and he knew I knew. Every time we looked at each other we said, with our eyes: I know you robbed me, I know you know I robbed you .

I remember the list of Chilean presidents who had studied at my school. I remember that when teachers reeled off that list, they omitted the name of Salvador Allende.

I remember saying “my school” with pride.

I remember the Subordinate Noun Clause and the Subordinate Adjective/Relative Clause.

***

I remember the vocabulary exercises, which were full of strange words that we’d repeat later, dying of laughter: commiseration, skirmish, bauble, knickknack, iridescent, vindicate, craggy, succinct .

I remember that Soto got dropped off at school by the chauffeur who drove for his father, a military man.

I remember that the English teacher gave a bad grade to a student who had lived in Chicago for ten years, and later said, ashamed, “I didn’t know he was a gringo.”

I remember stupid teachers and brilliant teachers.

I remember the most brilliant of all, Ricardo Ferrada, who, during the first class of the year, wrote a Henry Miller quote on the board that changed my life.

I remember teachers who wanted to sink us and teachers who wanted to save us. Teachers who thought they were Mr. Keating. Teachers who thought they were god. Teachers who thought they were Nietzsche.

***

I remember that gang of homosexuals in the fourth grade. There were five or six and they always sat together, talked only to each other. The fattest one wrote me love letters.

They never played any sports, and the few times they went out to recess, they got teased and hit. They stayed in the classroom instead, talking or fighting among themselves. They shouted “Bitch!” and threw their backpacks at each other’s faces or onto the floor.

Читать дальше