“I think what we did the first time around was right enough.”

I shifted on the rug like a drunken snow angel, and for a time, I may have drifted off. When I opened my eyes, she was standing over me, holding out her hand. “Let me show you something.”

She led me up the stairs, past a museum of bathing products on display, our stoned legs teetering beneath the unfamiliar weight of our sluggish bodies. Stopping at a dark room, she gave a tug at the string of another dragonfly lamp, which cast a warm orange halo over what soon revealed itself to be the music room. This was the space in which the Mackenzie of old dwelled: bass guitars upright in stands, an old Peavey amplifier in the center of the room, six-strings (electrics and acoustics) against the wall, an electric piano off to the side. It had the retro charm of a Haight/Ashbury recording studio circa 1967. I stood at the threshold and marveled.

Mack flipped a switch and the amp buzzed to life, its tubes shimmying at the fresh current of electricity. She grabbed a bass, sat down on the amp, turned the volume knob, and allowed her fingers to wade over the frets. The low notes glided up into the rafters, graceful yet commanding, smoothly rupturing the night.

She looked up at me. “Plug in. Let’s see what we remember.”

* * *

There are some of us who never had a choice. It was always going to be this way. Whether graced with talent or not, we were going to spend our lives in this often turbulent but always embracing sea. If we can make music, we make it and there’s no hope of turning off the spigot. And if we can’t, we listen and obsess. It becomes the Dewey decimal system by which our world is organized. We see a cheerleader in pigtails and think, Isn’t that skirt a little too Oh-Mickey-you’re-so-fine? We see a guy in a blazer with his sleeves rolled up and realize we’ve been neglecting that Mike + the Mechanics cassette boxed up in the attic all these years. Every unheard song out there is like the last page of a book: it has the answer. We know that this new album we just shelled out ten bucks for will somehow make us more complete, that it will plant one more post in the architecture of our selves.

People like us become someone different for a while when we fall in love with new music. The transformative qualities are real, even if they are imagined. In my Simon & Garfunkel mode, I was a little more cerebral and poetic in a Carl Sandburgian way; I cut back on the cursing in favor of actual words. When I was into Bob Marley’s Exodus , I was a more laid-back me. When listening to Misfits by the Kinks, I spoke with a bit of a sneer. I felt a little tougher during my enchantment with Public Enemy. I channeled a haughty impenetrability during the weeks when I thought OK Computer was God’s gift. I was a jittery little fuck in my Police phase, what with all that nervous reggae crammed into those albums, and in my Jackson Browne period I grew a beard. (I don’t know why. He didn’t have one.) It’s a junkie’s hunger and it springs forth from your subcellular components—organelles, I think they called them in biology class; maybe nuclei, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus. Occasionally, it feels like a prisoner’s existence because we don’t always choose the object of our obsession. An intense interest in the Muzak of Sven Libaek and the Carpenters has never landed panties on any guy’s floor. But in certain very limited circumstances, being yourself has.

The point is, we are happy to be powerless to resist the thrill of a new sound. You can leave the cell door unlocked. Nobody’s making a run for it.

That’s some of us.

Others aren’t nearly so afflicted. There is no pain, no suffering, no Sandburg, no sneering. There is just the angelic simplicity of being absorbed in your song. That was Mackenzie. And what a thing to hear. What a thing to watch. The way that the bass roots a song, gives it its steady footing and its ability to move—that’s what Mackenzie always lent to the Tremble machinery. As we strummed and plucked in the meek orange light of her upstairs room, the years melted away. I watched her falling into herself, into that unshakable peace, mellow and confident, following herself out of somewhere and into somewhere else.

When we finished playing and set down our instruments, she dropped her hands into her lap. “I don’t mean to bring the discussion back to my body, but I should probably tell you that I have breast cancer.” She winced apologetically. “I hate saying it that way, but there really are so few euphemisms.”

I looked at her, thunderstruck. “What?”

“I’m not sure why I just told you that,” she said. “Because really, I’m totally fine. They got it early. Nobody’s telling me not to buy green bananas or to stay away from the collected works of Dumas.”

“Holy shit. Why didn’t you tell me this earlier?”

“When was earlier?”

Four months ago, while applying deodorant after a shower, she noticed a lump in her armpit. She would’ve ignored it, constitutionally hardwired as she was with an inability to panic, but having lost her mother six years ago to Hodgkin’s, she read the genetic writing on the wall. Within ten days, she’d undergone a mastectomy. Her most recent round of chemo had been earlier that week.

“I just assumed you had access to my medical records, showing up here with a stash of antinausea,” she said with a coy twinkle.

“Jesus, Mack.” I felt ashamed, prattling on all night about the need to be taken seriously as an artist, bitching about bad photographs of me eating Mexican food. “You must’ve wanted to slap me all night.”

She didn’t speak up to say otherwise.

“Are you okay? Who’s taking care of you?”

“I’m no recluse, Teddy. I’ve got friends. Really good ones, it turns out.”

There was, she assured me, no shortage of people populating her fridge with Tupperwared meals she was too nauseated to eat, soothing her with six-packs of Canada Dry ginger ale. For the time being, she was still tethered to the treatments every few weeks, but the end of that vicious battery was approaching, and her doctors were optimistic that she would soon have her forehead stamped with the words In Remission, that sought-after designation that somehow still sounded ominous.

For a long moment, the only sound was the high constant hum of the amp.

“I also have an ex-husband checking in on me,” she volunteered.

I flinched in surprise.

“Remember Colin Stone?”

“The Sony rep? Sure. The Dire Wolf. What about him?”

“He’s at MCA now, but . . .”

My jaw went slack. “You married Colin fucking Stone?”

And who wouldn’t? Colin was a lifer in the music business, a gregarious, distinguished-looking record exec with dense hedges of gray hair and an enveloping grin. He had a really enthusiastic handshake—he swung you a bit, he was so damn happy to see you, he might just pull you right into his suit jacket—and was always either on his way to a leisurely, lubricated meal or just returning from one. He was our main point of contact when Sony signed us, and he brimmed with encouragement at every meeting, even later on when we couldn’t catch a cold. Colin was a good bit older than us, so it often felt as though someone had brought a dad to our Mirabelle Plum marathons, but a dad who went out more nights a week than we did and who drank all of us under the table in passing.

As a member of the band, Mack had never viewed him in a romantic light. But a few years later, she told me, when she was in her graduate program in New York, they ran into each other on an elevator and realized they lived in the same building. Right then and there, he invited her to tag along at a dinner with the Flaming Lips (regular people have dinner; Colin always had a dinner), and in an aberrant move, she accepted. Another invitation followed, and soon she was accompanying him to record release parties and on visits to his ailing mother (an impossibly ancient Czech woman who made a mean mushroom soup). They even got into a rather delightful minor car accident together.

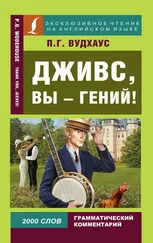

Читать дальше