“He may be the only one who takes my call, but after him, Warren, then Mackenzie. That would be the plan.”

At the mention of Mack’s name, Sara’s eyes skipped down to her glass. She changed the subject. “How’d it go with Marty Kushman today?”

Marty was the managing partner at my firm, which meant he faced a daily diet of tattletales, gossip, and all interoffice squabbles that required the services of a referee. He was also the guy you talked to when you wanted out.

“It went okay. I told him I was leaving but not quitting. A leave of absence, nothing permanent. Marty was cool about it.”

“He didn’t laugh in your face?” It was a cruel and entirely reasonable question.

“I didn’t tell him why I was leaving. People leave law firms all the time. He didn’t ask a lot of questions.”

“Here’s a question: Does your father know?”

“I’ll tell him when I tell him,” I said, irked at the very thought of his knee-jerk disapproval, how upon learning of my latest attempt to disgrace the family, he’d slam down his Legal Intelligencer and howl, “Goddamn that kid!” Had I forgotten all those scathing reviews, the hollow venues, the laughable royalty checks?

Sara swigged her wine as if she needed it. How rudderless she must’ve felt, one man in her life heaving himself into a midlife tempest that was guaranteed to put distances between them, and another man returning from the past only to discuss goodbyes. I knew the prospect of revisiting that old minefield of memories with Billy was weighing heavily on her.

“Sara, I know this is all very abrupt and very weird, but I don’t want you to worry. About us.”

“I’m not worried about us,” she said a little too pointedly.

I cocked my head. “What does that mean?”

She swirled her glass and picked up a cheese cube, and for a moment, Sara seemed to drift up into the restaurant’s Middle Eastern music. A plucked guitar and the taut rapping of a goatskin drum coasted gently over our heads. At last she returned to me.

“Teddy, I think you came back from Switzerland a different person. But . . .”

“But . . .”

“But that’s probably not the worst thing in the world.”

I leaned across the table, unhitched her hand from her glass, and took her long, spindly fingers in mine. “I’m going to be there for you as you go through all this divorce stuff. You know that, right?”

She gave my hand a dismissive pat. “You don’t have to go all serious on me. I’m not afraid of what you want.”

It was those words that had stayed with me. Why wasn’t she afraid of what I wanted? I was terrified of what I wanted.

As I sat there facing the Baltimore harbor with Jumbo and the daughter of his ex-wife, I realized I’d crossed the Rubicon. The simple act of approaching a former band member and inviting him into my world of delusion had brought this folly outside the safe confines of my head. It would be harder now to turn back.

When the performance ended, Ingrid shot out of her seat and made for one of the fuzzy characters, some sort of moose. Jumbo tore after her.

It amazed me that this little girl felt comfortable in Jumbo’s charge—Oh Jumbo, tell me the story about how Curious George went to Marseille and got the clap—but it amazed me all the more that this Israel fellow felt comfortable leaving his child alone with him. Jumbo was not reliable and he was not smart, and for most of his career, he’d been out of work. Nor was he overeducated. He’d attended Guttenberg University, which might have a stately collegiate ring to it, like some liberal arts school for trust-funders or an ancient, woodsy institution in Bavaria. It was, in fact, a correspondence course outfit in the Cherry Hill Mall. The minute you even considered enrolling, you were in the running for valedictorian.

But as I watched him hawk over this child, there was no mistaking that this family had, in its own deeply peculiar way, come to accept him. And whatever complications existed between him, Sandy, and Israel, they no doubt sensed the clunky genuineness of his affection for their kids. Perhaps I was grasping at straws here, but was that evidence of growth? Maybe in his own microscopic, stunted way, Jumbo was evolving.

On the walk back to the car, an exhausted Ingrid slung over Jumbo’s shoulder with her thumb in her mouth, we passed a string of bars. Their doors were wide open on this pleasant Saturday afternoon, each one dark and empty of patrons, a scattering of bartenders and waitstaff lounging about. A chalkboard outside one establishment advertised the evening’s live entertainment. The Naked Mannequins were headlining, Pete Sake was opening. Open mic from six to eight. Dollar drafts from five to six.

I stopped in my tracks. “I have an idea. Let’s come back down here later.”

“Oh, hell yeah! Celebration is in order!”

“No. It’s an open mic. I want to play you a few of the new songs tonight, right here in this bar.”

The impulse was a protective one, for my songs, and for Jumbo’s first impressions of them. A maiden voyage through a song is like a first date, painting it with sensation and imagery that becomes forever inseparable from the music. It was asking an awful lot of my new songs to make themselves arresting when first heard in a dank basement, a single naked voice fighting its warbled chirp over a dampened guitar. A stage would serve the music better, kindle the flames of inspiration for Jumbo such that he would be moved to contribute to them, to make them better.

Jumbo grinned eagerly at my suggestion. “I like the way you think, Mingus.”

As we approached the family minivan, I took hold of Jumbo’s arm. “Look, this time around, if this actually ends up happening—and it’s a long shot if there ever was one—I need you to be better. Do you understand? I’m too old to deal. You’re going to go easy on the booze.”

“No worries, man. My tolerance is much better than it used to be.”

“You’re going to sleep when it’s nighttime, like everyone else. You’ll show up for things. You won’t tell anybody they look pregnant. You’ll wear clothes, all the time. We’re going to go about this very differently. You’re going to go about this very differently.”

Jumbo either said “I’m in” or “Amen.”

“Another thing. No makeup.” I was referencing his regrettable period of wearing heavy eyeliner and mascara on stage. It was garish and weird and made him look like the Phantom of the Opera.

Jumbo smirked in fond remembrance as he nestled the sleeping child into the car seat. “I’d forgotten all about that.”

“You’re lucky.”

So Sandy was a surprise. Older and frumpy, with kind eyes jailed behind outsized eyewear, she looked like a new grandmother, down to the flaking rouge. Once upon a time, Jumbo considered it his right to work his crass charm over pretty little things in bars, sauntering up to them and saying things like “Why don’t you just tell me your safe word now?” Damned if it didn’t work every time. None of those women looked like Sandy. Though maybe their mothers did.

When we returned to the house after the bar later that night, gripping guitar cases like decaying versions of our former selves, Sandy greeted us in the foyer. In low tones suggesting sleeping children in earshot, she invited us to deposit our instruments in the basement and join her and Israel for a drink in the den.

“So, I see you married Mrs. Doubtfire,” I remarked once we’d descended to the seclusion of Jumbo’s subterranean living quarters.

Jumbo didn’t assume it was an insult. “Doubtfire was a handsome older woman, wasn’t she?”

“You do know that was Robin Williams.”

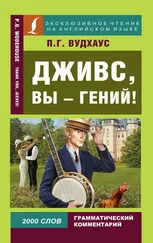

Читать дальше