Pink is what red looks like when it kicks off its shoes and lets its hair down. Pink is the boudoir color, the cherubic color, the color of Heaven’s gates. (Not pearly or golden, brothers and sisters: pink .) Pink is as laid back as beige, but while beige is dull and bland, pink is laid back with attitude . The Don CeSar (275 rooms and all the water sports a bipedal mammal can handle) wears that attitude well. It knows that it looks as if it were carved out of bubblegum, as if it mutated from a radioactive conch patch, as if it leaked from the vat where old flamingos go to dye — but the Don CeSar doesn’t care. It simply winks, lazily flaunts its pigmentation, and like a cartoon panther who’s peddled its last lucrative roll of home insulation, turns its face to the sun.

Because pink, unique in the spectrum, is essentially paradoxical, the decorator’s paint of choice for Mexican brothel and New England nursery, it’s called upon to signify both naughtiness and innocence. Thus when I describe the Don CeSar as architecturally affectionate, a kind of structural kiss, I’m referring not only to hot and hungry honeymoon osculation but to that chaste smooch a young Esther Williams used to blow to all the shivering northern masses just before she dove into a pellucid pool way back there in a more innocuous age.

In a different mood, I’m also inclined to think of the Don CeSar as shrimp cocktail for the eyes. And as long as it doesn’t change color, I’ll keep stopping by every year or so for a taste of it. Someday, I may go so far as to book a room there. You can tell it to the CIA, you can tell it to the FBI, you can tell it to Jerry Falwell and all the little Falwells: when it comes to beach hotels, comrades, I’m a dedicated pinko.

National Geographic Traveler, 2000

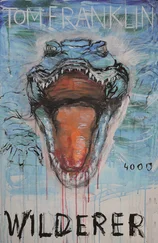

The Cannibal King Wants His Din-Din

When the roosters that scratch in the yard of Brastagi’s best hotel crowed me awake that steamy tropical dawn, I, personally, wasn’t feeling all that cocky. In retrospect, however, I suppose I might be forgiven had I rolled out of bed with a bit of attitude because — believe it or not — before the Sumatran sun would set, I, an unassuming, modern, civilized commoner with a taste for donuts and garden vegetables, would be brandishing the savage scepter of a man-eating monarchy. That’s right. Tom, King of the Cannibals!

The previous day had been interesting enough, much of it spent at a jungle outpost that functions as an orangutan rehabilitation center. No, no, Indonesia’s population of big red apes isn’t plagued by drug or alcohol problems, but some of the goofily beautiful animals (imagine Arnold Schwarzenegger crossed with Lucille Ball and the prototype for the Gerber Baby) do suffer an addiction of an even more dangerous sort. Captured as infants to be pets in the households of the rich, they develop a fondness for and a dependency on human companionship. When they grow too large and powerful to be any longer manageable around the house, the domesticated primates are turned over to a government agency that transports them to a wilding compound in the mountains where they’re gradually taught to fend for themselves and be mistrustful of men. An excellent idea, of course, since every living thing on this planet, including men, would be wise to be mistrustful of men. But I digress.

My little group was in northwestern Sumatra to raft the Alas, a remote river that cuts through the rainforest with a silver track, offering a few thrilling rapids, but, most alluringly, daily opportunities to spy on truly wild orangutans and, if we were lucky, an Asian rhino or a tiger or two. (We tried not to consider possible encounters with cobras or kraits.)

An exploratory party from Sobek, the California-based adventure company, had accomplished the very first rafting of the Alas only months before, and we — eight paying passengers, four Sobek guides, and an Indonesian forest ranger who spent his spare time reading Louis L’Amour westerns — were to be the second rafters ever to run the strand.

So serenely did we conceal our nervous excitement that morning that we could have been compared to a bag of marshmallows at a Girl Scout camp. After nibbling at the hotel’s advertised “American breakfast” (chilled fried eggs, diced papaya, and processed cheese), we hurried aboard a snub-nosed buslike vehicle of unknown manufacture to be driven to the spot deep in the leafy hills where we’d be putting our inflatable boats in the water.

Adventure travel is by definition unpredictable, however, and we never reached the Alas, alas, at least not that day. Instead, acting on a fortuitous tip from a Mobil Oil geologist that a rare daylong exhumation ceremony was about to unfold in an isolated village of the Karo Batak tribe, we detoured, parallel-parked between two water buffalo, and, following the oilman’s crude map, hiked five miles into an anthropologist’s dream.

Aside from the occasional oil explorer, timber cruiser, or misguided Christian missionary, the Karo Batak had never been exposed to blue-eyed devils. Yet, when — blue eyes as wide as poker chips — our foreign mob suddenly appeared out of nowhere, we were received as honored guests. So gracious was their hospitality, in fact, that after a confab, tribal leaders declared that a pair from our group would be crowned king and queen for the day.

Being both very strong and very sweet, the guide Beth was a logical choice for queen. Why they chose me as their king I haven’t a clue. Certainly it had nothing to do with my literary reputation, although some novelists are known to practice verbal cannibalism, biting and gnawing on one another insatiably at cocktail parties or in reviews.

At any rate, our hosts escorted Beth and me to sexually segregated longhouses where they wrapped us in regal sarongs and other colorful raiments and hung about thirty pounds of solid gold jewelry — the village treasury — from our respective necks and appendages. (They must have figured we were too weighted down to skip town.)

There was then a royal procession back to the principal longhouse, where now on display were the remains of seven persons recently exhumed from the graves where they’d lain for years while their families saved enough money to fund the ceremony that would finally usher their spirits into the Karo Batak version of heaven. The bones were lovingly washed, dried, and stacked in seven neat piles, a skull atop each pile like some kind of Halloween cherry. Then the celebration began.

Beth disappeared into a shadowy corner where she remained for hours (afraid, perhaps, that her regal counterpart might demand his conjugal rights?), but my “subjects” and I commenced to dance ritualistically around those graveyard sundaes. Danced around them and around them and around them. Energized by betel nut, the chewing of which stained my numb mouth the color of Buck Rogers’s rocketship, and inspired by two talented groups of drummers and snake-charmer flute tooters, I managed to learn the proper repetitive steps and to tirelessly dance the day away.

Now, to be quite truthful, the Karo Batak appeared innocently tame and, despite periodic reports to the contrary, are believed not to have lunched upon any of their fellows in about four generations. Many are Christian (leading me to wonder if they might especially enjoy Holy Communion: that is, “swallow the leader”). Nevertheless, when toward evening an unappetizing zombie-gray stew was served, we intruders politely excused ourselves — as an abdicating monarch, I shook every hand in the village — and took the long muddy trek back to our bus.

At the very worst, the stew meat was dog, and probably it had come from upcountry cousins of those Hotel Brastagi roosters who had cock-a-doodled our reveille. Be that as it may, I shall never cease to insist that once upon a time, in the tiger-haunted hills of Sumatra, I reigned as King of the Cannibals. And at those who might dispute that claim, I’m fully prepared to hurl the ancient and traditional curse of the Karo Batak: “I pick the flesh of your relatives from between my teeth.”

Читать дальше