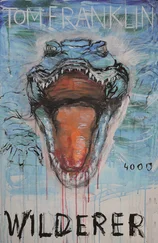

Black Book, 2002

What Is the Function of Metaphor?

If, as Terence McKenna contended, the world is actually made of language, then metaphors and similes (puns, too, I might add) extend the dimensions and expand the possibilities of the world. When both innovative and relevant, they can wake up a reader, make him or her aware, through the elasticity of verbiage, that reality — in our daily lives as well as in our stories — is less prescribed than tradition has led us to believe.

Metaphors have the capacity to heat up a scene and eternalize an image, to lift a line of prose out of the mundane mire of mere fictional reportage and lodge it in the luminous honeycomb of the collective psyche. They can squeeze meaning out of the most unlikely turnip.

On a personal level, I was asked at a bookstore reading once if my fondness for metaphors wasn’t a gimmick. In response, I asked the questioner, “Were Hemingway’s short declarative sentences a gimmick? Were the long convoluted sentences of Faulkner a gimmick?” In both instances, the answer is emphatically no . When Hemingway and Faulkner distilled their respective realities into language, what we encounter on the page is the stylistic reflection of those realities. It’s how those two writers saw the world. Or, more accurately, it’s how they were compelled to represent what they saw. In my case, because I’m fascinated by words, mythology, and transfiguration, it’s hardly surprising that I’d refract life through the polychromatic lens of metaphor and simile.

Admittedly, I get a kick from simply playing with language, but I try to make it a point not to create metaphor for metaphor’s sake; to never fashion them carelessly or employ them arbitrarily. I insist that whenever possible they not only spring out of trapdoors or closets but that their “Surprise!” has contextural pertinence .

Ultimately, I use such figures of speech to deepen the reader’s subliminal understanding of the person, place, or thing that’s being described. That, above everything else, validates their role as a highly effective literary device. If nothing else, they remind reader and writer alike that language is not the frosting, it’s the cake.

Asked by Inside Borders, 2003

According to Fellini, “The visionary is the only true realist.” Before we dismiss that declaration as the ravings of a… well, a visionary, we should consider this:

Most of the activity in the universe is occurring at speeds too fast or too slow for normal human senses to register it, and most of the matter in the universe exists in amounts too vast or too tiny to be accurately observed by us. With that in mind, isn’t it a bit unrealistic to talk about “realism”?

What Tom Wolfe and the other champions of naturalistic writing would have us accept as realistic content is actually the behavior patterns of a swarm of fruit flies on one bursting peach in an orchard with a thousand varieties of strange fruit stretching beyond every visible horizon. Granted, those fruit flies are pretty damn interesting, but from the standpoint of “reality” they are hardly the only game in town.

Since the so-called fabric of reality has been historically perforated with false assumptions, and is continuously stained by myriad hues of subjectivity, any of us poor fools who believe we’re writing something real may actually be the unwitting butts of a fiendish cosmic joke.

On the other hand, there’s a point of view shared by most mystics and many theoretical physicists that purports that everything in the universe, large or small, is simply a projection of our consciousness. So, one could make a case for all writers being realists, including those who write about the secret lives of inanimate objects every bit as much as those who focus on jury deliberations or coming of age in rural Nebraska.

Asked by Contemporary Literature, 2001

What Is the Meaning of Life?

Our purpose is to consciously, deliberately evolve toward a wiser, more liberated and luminous state of being; to return to Eden, make friends with the snake, and set up our computers among the wild apple trees.

Deep down, all of us are probably aware that some kind of mystical evolution — a melding into the godhead, into love — is our true task. Yet we suppress the notion with considerable force because to admit it is to acknowledge that most of our political gyrations, religious dogmas, social ambitions, and financial ploys are not merely counterproductive but trivial. Our mission is to jettison those pointless preoccupations and take on once again the primordial cargo of inexhaustible ecstasy. Or, barring that, to turn out a good thin-crust pizza and a strong glass of beer.

Asked by LIFE magazine, 1991

To return to the corresponding text, click on the reference number or "Return to text."

*1When I wrote those lines, Thompson was alive and in bloom. Now, with his sad demise, still more color has faded out of the American scene. Where are the men today whose lives are not beige; where are the writers whose style is not gray?

Return to text.

The reader who might notice slight discrepancies between some of the pieces in Wild Ducks Flying Backward and the way they appeared in those venues where they were initially published may be assured that there’s a simple explanation. Some of the original articles had been pruned and truncated, usually for reasons of space, and I’ve restored those cuts. In addition, while reviewing the older pieces, I found that I had occasionally used words or phrases for which I now saw more interesting, effective alternatives. What could I do but substitute? A writer who passes up any opportunity to refresh his language is not a writer you can expect to meet in Heaven.

T. R.