‘That was inconsiderate of him.’

‘He’s an old friend. I don’t mind.’

‘You live near here?’

‘Yes, not far. South Kensington. What about you?’

‘Oh, it’s like another world to me, an area like this. I live in South East London. On a council estate.’

After a pause, she said: ‘Do you mind if I ask you for something? A request, I mean. A piece of music.’

I felt a sudden tight grip of anxiety. You see, the reason I never made it as a cocktail bar pianist was that my repertoire was never wide enough, and I was hopeless at playing by ear. Customers are always asking pianists to play things and the only way I could have covered myself against situations like this was by learning every standard in the book. That would have taken months. It usually took me a few hours to get a piece into shape, sometimes more. Take ‘My Funny Valentine’, for instance. It’s not a difficult tune, yet something about the middle eight had been defeating me and it had just taken me two days to get it sounding exactly how I wanted. I’d been listening to some of the most famous records, seeing how the masters had handled it and working out what I thought were some pretty neat substitutions of my own. I could play it well, now, I thought, but that had been the result of two days’ hard work, and anything she was to ask for, even if I knew roughly how the tune went, was bound to come out sounding amateurish and embarrassing.

‘Well… try me,’ I still said, for some reason.

‘Do you know “My Funny Valentine"?’

I frowned. ‘Well… the title’s familiar. I’m not very quick at picking things up, though. Can you remind me how it goes?’

Wouldn’t anybody have done the same thing?

I think that was the best version I’ve ever played. I’ve never topped it since: it was a real heart-breaker. The copy gives G7 as the chord in the second bar, but most times — and in the tenth bar, too ― I was substituting a D minor seven with a flattened fifth, only I was playing the second inversion, with an A flat in the root. You should try it. It really darkens the tune up. Then in the middle eight, instead of those augmented B flats, I was putting straight A flat major sevens — and once I even tried a minor ninth, which I hadn’t even thought of before then (fortunately I was able to communicate the news to my right hand just in time). I stretched it for six choruses, playing quiet to start with but really hitting the keys, really thickening the chords by the end. For the final chord I went down to C minor, and my last note — I can remember it now — was an A natural, right at the top. I’ve tried it since, and it didn’t sound as good. It sounded just right at the time.

There was silence at first, then she started clapping, and then she came over to the piano. I turned around and faced her. We were both smiling.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘That was beautiful. I’ve never heard it played like that before.’

I couldn’t think of anything to say.

‘My father used to love that tune,’ she continued. ‘He used to have a record of it. I used to listen to it a lot, but… you played it very differently. And you’d really never played it before?’

I laughed modestly. ‘Well, it’s amazing what you can do. When the inspiration’s right.’

She blushed.

After a couple more numbers the manager came over and told me that I might as well go home. Nothing was said about coming back to play the next week. He gave me my cash and then went over to start closing up the bar.

‘Oh well,’ she said, ‘ I enjoyed it. So would a lot more people if they’d been here.’

I finished packing my music away into a plastic bag and said: ‘Do you mind if I walk you home?’ She looked hesitant. ‘I don’t mean anything funny. I only mean as far as your door.’

‘All right, that’s very kind. Thank you.’

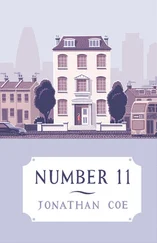

And so that was as far as I got that evening — to her door. It turned out to be quite a door, all the same. About twice my height, at a modest estimate. It seemed to lead into some kind of mansion: one of those impossibly massive and gorgeous-looking Georgian houses you find in Onslow Square and those sorts of areas.

‘You live here?’ I said, craning my neck to look up at the top storey.

‘Yes.’

‘On your own?’

‘No, I share it with another person.’

I tutted. ‘That must be awfully cramped.’

‘I don’t own it or anything,’ she said, laughing.

‘You rent it? Really? How much a week? — Round it down to the nearest thousand if you like.’

‘I work here,’ she said. ‘It belongs to this old lady. I look after her.’

It was a warm early summer’s evening. We were standing on the pavement opposite the house. Behind us was a tall laurel hedge, and behind that, a small private park. Above us was the silver light of a street lamp. I leant against the lamp post and she stood quite close beside me.

‘She’s just a frail old lady. Most of the day she sleeps. Twice a day I have to take her up a meal — I don’t have to cook it, there’s a cook to do that. I can’t cook. I have to get her out of bed in the morning, and get her into bed at night. In the afternoon I have to take her up a cup of tea and some biscuits and cakes, but sometimes she doesn’t wake up for long enough to have them. I have to do her shopping for her, and go to the bank, and things like that.’

‘And what do you get for doing all this?’

‘I get some money, and I get some rooms of my own. There, those are my rooms.’ She pointed up at two enormous windows on the second floor. ‘Most of the time I don’t have to do anything. I just sit up there, all day sometimes.’

‘Don’t you get lonely?’

‘There’s a telephone, and a television.’

I shook my head. ‘It sounds, well, very different to the life I lead. Very different.’

‘You must tell me about it.’

‘Yes, I must. Perhaps,’ I ventured, ‘perhaps some other time?’

‘I have to go inside now,’ she said, and she crossed the road hurriedly.

I followed her and she unlocked the front door with a Yale key which looked absurdly small and puny for the task. There were three steps up to the door: I was standing on the second, and she was on the third, which made her seem quite a lot taller than me. When the door opened, I glimpsed a dark hallway. Madeline disappeared for a moment — I could hear the click of her heels on what seemed to be a marble floor — and then the light was switched on.

‘Jesus Christ…’ I said.

While I was peering in, not even bothering to hide my awe and astonishment, she was picking up an envelope which must have been posted by hand through the letterbox. She opened it and read the letter.

‘It’s a note from Piers,’ she said. ‘He came round after all. How stupid of him.’

I was standing there like some idiot, not saying anything.

‘Well,’ said Madeline, ‘this is as far as you go.’ She started to turn away. ‘Good night.’

‘Look — ’ Forgetting myself, I had laid my hand on her arm. Her grey eyes looked at me, questioning. ‘I’d like to see you again.’

‘Do you have a pen?’

I had a cheap plastic biro in my jacket pocket. She took it and wrote down a telephone number on the front of the envelope, beneath the word ‘Madeline’ which had been put there by her friend. Then she handed it to me.

‘Here. You can phone me. Any time you like — day or night. I don’t mind.’

And after saying that, she closed the door gently in my face.

*

Samson’s wasn’t very crowded — the weather must have been keeping people away — and we had the choice of whether to sit in the eating part or the drinking part.

Читать дальше