‘There’s nothing wrong.’

I took hold of her chin and forced her to look at me.

‘Yes there is. Isn’t there?’

She looked away.

‘I don’t want to talk about it.’

My fingers had been covered with pickle and tomato sauce. She took one of the paper serviettes and wiped her face clean.

I sighed. ‘Tell me, will you? You owe it to me.’

She tried to meet my gaze but had to look away as she said, brokenly, ‘I want… a change.’

‘A change?’

‘In this relationship.’

I frowned.

‘What sort of change?’

‘You know what sort,’ she said, looking up again.

‘No I don’t.’

For several seconds we stared at each other, two pairs of eyes in angry, hopeless deadlock, straining to communicate and yet straining to block each other out. Finally Madeline broke away.

‘God, you’re stupid,’ she said. ‘I’ve never known anyone as stupid as you, William.’ She stood up and put her bag over her shoulder. ‘I’m going.’

‘Going where?’

‘Home.’

‘Don’t be silly.’

‘I’m not being silly. I’ve had enough and I’m going home.’

‘I’ll come with you to the bus-stop.’

‘Forget it. I don’t want you to. I’d rather go on my own.’

I stood up, too.

‘Will you stop messing around? Are we going to talk about this properly, like two — ’

She pushed me back down into my seat.

‘Shut up and finish that cheeseburger.’

And before I had time to stop her, she was off, running down the staircase and disappearing from view. I sat there, baffled. In front of me was a plastic carton containing a half-eaten cheeseburger: a potent symbol of a failed relationship if ever I saw one. After a few moments I pushed it into the waste-bin and left the restaurant myself.

There was no sign of Madeline out in the street. I knew which bus-stop she would be walking to, but there seemed no point in following her: better to let this mood subside, and maybe call her tomorrow. The evening was turning colder, and there was a damp mist in the air. I buttoned up my thin old raincoat, thrust my hands deep into the pockets, started to wander aimlessly up the street and then struck out in the direction of Samson’s.

It was a long shot, but it paid off: Tony was there. I didn’t want to speak to him right away, though, so I sat at a table in the corner and ordered a bottle of wine, which I began to drink on my own, slowly and methodically. The next thing I knew, it was three-quarters empty. The place was practically deserted, so there wasn’t much in the way of distractions — conversation, clinking glasses, the scraping of chairs — to prevent me from listening to his piano-playing. We had ‘Night and Day’, ‘Some Other Time’, ‘Blue in Green’ and, finally, ‘My Funny Valentine’. Though I say it myself, it wasn’t as good as the version I had played for Madeline that night. It was more polished, but less emotional. It got to me, all the same, prompting me to wander over to the piano, before Tony had a chance to start his next number.

‘Hi.’ He seemed genuinely pleased to see me. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘When’s your break?’ I asked.

‘Well, I could take one now.’

‘Come and have a drink, then.’

We ordered another bottle of wine, even though he didn’t seem to drink much of it, and I filled him in on the argument with Madeline. I don’t know what I expected to gain from confiding in him in this way. Men don’t tend to be a great deal of use to each other at times of emotional crisis, and I found myself wishing that there was some woman I could have gone to, someone who wouldn’t have felt embarrassed about hugging me, to start with, and then discussing the whole thing openly. Tony, I could see, was also suffering from the temptation to say something along the lines of ‘I told you so’. I wasn’t going to let him do that.

‘Well, I might as well try to forget it,’ I said eventually.

‘I think that’s a good idea.’

‘I’ve got other things to think about. Lots to get on with.’

‘Exactly.’

‘Besides, I can phone her in the morning.’

He looked at me, smiled and shook his head.

‘You don’t think you should leave it a bit longer than that?’

It occurred to me that what he was saying was something in the nature of a final break: a prospect which, as soon as I contemplated it, plunged me into fear and panic. I had a momentary sensation of falling and weightlessness, like you get in a lift when it descends too quickly. I shivered.

‘We’ll see. I’ll think about it’. To avoid discussing the matter further, I said: ‘I’ve written a new piano piece.’

‘Really?’ said Tony. ‘How does it go?’

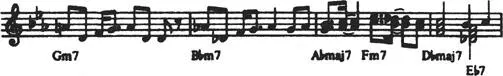

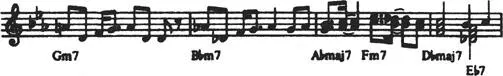

I had indeed completed ‘Tower Hill’ only the previous evening. The last four bars of the middle eight had turned out to be rather complicated, involving further modulations and a more elaborate approach to the melody, but I liked them and felt that they fitted. I had got, you may remember, as far as an F major seven, held for a whole bar. Well, for the second half of that bar I had now added an F sharp diminished, with a little linking figure on top which went like this:

This now led into a G minor (picking up on the one two bars earlier), an unexpected B flat minor, and then on to a strong A flat major from which, by descending thirds, I quickly progressed to a D flat. From there an E flat seven was the obvious way to get back to the beginning of the piece, although it seemed to need a little help by having some extra harmony voiced in the right hand:

I liked the patterns of thirds in the penultimate bar of this section, and I liked the momentary sense of fullness in the fourth, as you poised on that last chord before returning to the main tune. But naturally, now that the piece was finished, it was open to interpretation in all sorts of different ways, and a performer was under no particular obligation to follow my voicings. I was already keen to hear what another pianist would make of it.

‘Do you have any paper with you?’ I asked Tony.

‘Sure.’

He always carried a slim leather briefcase with him, full of song-copies. From this he now produced a sheet of blank manuscript paper which he handed to me, along with a pen. Within a few minutes I had written it out. I pushed it back across the table towards him and his dark, intelligent eyes scanned it keenly, picking out the highlights and constructing, in his mind, a sound-picture of the total effect.

‘Very interesting,’ he said. ‘Quite nicely done, that.’

He tried to return it to me but I stopped him.

‘Will you play it?’

‘What, now?’

‘Yes. I’d like to hear it.’

He considered it; and then handed me back the paper.

‘No. You play it.’

If I hadn’t been slightly drunk, and if the place hadn’t been so empty, I would never have had the nerve. Apart from anything else, I’d never even played it on a piano before, only on an electric keyboard, which isn’t the same thing at all. Be that as it may, I found myself walking over to the piano, sitting down on the stool, and trying to prepare myself by breathing deeply. A couple of seconds later I had hit the first chord.

Some musicians will tell you that alcohol can improve your playing by helping you to relax. This is not true. The only real relaxation comes from feeling confident about your material. The sort of relaxation offered by alcohol is nothing but a blurring of perception, which means that faults in your performance never distract you because you don’t even notice them. I was too drunk, that evening, to play a respectable version of ‘Tower Hill’. Exactly how it would have sounded to an objective listener I don’t know: all Tony would tell me afterwards was that I had made some mistakes. At least, that’s what he told me about the first half of what I played. The rest could perhaps best be described as an excursion into free improvisation.

Читать дальше