I left Moscow in a torrid heat. Yes, I said that already, I think, 93 degrees in the shade. They just announced over the loudspeaker that the temperature in Prague is 54 degrees. And it’s also raining.

33 No English translation of this interview could be found; therefore, I have translated from the Spanish. —Trans.

34 Translated by R. Sieburth.

My mother had died a few months before; I had started school, in a modest private residence with eight or ten pupils. I had not yet been struck by malaria, so I was able to lead a more or less regular life. We sang almost all the time, but also learned to count, read, draw. We were all happy there, I think. Our teacher’s name was Charito; she was very fat, but wonderfully agile for dancing, which she did often. My grandmother gave me a book to practice reading at home; it had probably belonged to my mother as a child. On the first page there was a text with some faces, each framed in a box with words of identification. The page was entitled “Human Races” and contained photos or drawings of children from different places and of different races. One of the children had thick lips and high cheekbones, features that gave him an animal-like appearance, a quality that was reinforced by a thick fur cap, which I assumed was his own hair and which went down past his ears. At the bottom it read: Iván, the Russian boy . In the evenings, when the house was immersed in sleep, I would take long walks. It was the offseason, those long months of inactivity immediately following the sugar harvest; the huge factory was at that time empty, except, perhaps, during the few days the machinery was being serviced. In the afternoon there were no workers, only an occasional watchman. If anyone asked me what I was doing there, I inevitably replied that the clock in my house had broken and my grandmother had sent me to check the factory clock. So I would go in. I’d cross the central body of the mill, wander its various naves, leave the buildings, and walk up to a mound of bagasse that was drying in the sun. I don’t recall now how I came to know about this solitary place or who showed me my way around the maze blocked at every turn by giant machines. Once there, I would sit down or lie on the warm bagasse. From a normal height, I would stare at a ravine that ended in a wall of mango trees. I knew that behind those trees ran the Atoyac River, the same river in which a few miles down my mother had drowned. No one passed by that place, or on the very rare occasion someone did, I would curl up in the bagasse and pretend that I was mimicking the iguanas and become invisible. One day a boy, about four or five years older than I, showed up. He was a complete stranger. It was Billy Scully, a newcomer to Potrero. Billy was the son of the chief engineer of the sugar mill, and he became, from the first moment, a born leader, though never a tyrant, whom we all admired instantly. Before the strength of his movements and the freedom emanating from his whole being, I felt even smaller. He asked me who I was, what my name was.

“Iván,” I replied.

“Iván what?”

“Iván, the Russian boy.”

Intuitively, I feel that my intimate relationship with Russia goes back to that distant source. Of course, Billy did not believe me, but he didn’t let on. I was a rather odd, very lonely, very capricious boy, I think. My problems with mythomania lasted a few years longer, as a defense against the world. Sometimes, later, after a few drinks, they would reemerge, which angered and depressed me to a disproportionate degree. The only exception was my identification with Iván, the Russian boy, which at times still seems to me to be the real truth.

AITMATOV, CHINGIZ. Trans. Mirra Ginsburg. The White Ship. Crown Publishers, 1972.

BENJAMIN, WALTER. Trans. R. Sieburth. Moscow Diary. Harvard University Press, 1986.

BERBEROVA, NINA. Trans. Philippe Radley. The Italics Are Mine. Vintage, 1993.

CANETTI, ELIAS. Trans. John Hargraves. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

CHEKHOV, ANTON. Trans. Constance Garnett. “In the Ravine.” The Portable Chekhov. Penguin Books, 1977.

CIORAN, E.M. Trans. Richard Howard. History and Utopia . University of Chicago Press, 1998.

FERNÁNDEZ DE LIZARDI, JOSÉ JOAQUÍN. Trans. David L. Frye. The Mangy Parrot: The Life and Times of Periquillo Sarniento. Hackett Publishing Co., 2005.

KARLINKSY, SIMON. Marina Tsvetaeva: The Woman, Her World, and Her Poetry . Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Letters: Summer 1926: Boris Pasternak, Marina Tsvetayeva, and Rainer Maria Rilke. Trans. Margaret Wettlin, Walter Arndt, and Jamey Gambrell. Yevgeny Pasternak, Yelena Pasternak, and Konstantin M. Azadovsky, eds. New York Review Books, 2001.

MANDELSTAM, NADEZHDA. Trans. Max Hayward. Hope Against Hope: A Memoir. Modern Library, 1999.

MEYERHOLD, VSEVOLOD. Trans. John Crowfoot. Arrested Voices: Resurrecting the Disappeared Writers of the Soviet Regime. Martin Kessler Books, 1996.

NABOKOV, VLADIMIR. The Real Life of Sebastian Knight . New Directions Publishers, 1992.

PASTERNAK, BORIS. Trans. Manya Harari. An Essay in Autobiography. Collins and Harvill Press, 1959.

PILNYAK, BORIS. Trans. Vera T. Reck and Michael Green. Mahogany and Other Stories. Ardis Publishers, 1993.

TSVETAEVA, MARINA. Trans. J. Marin King. A Captive Spirit. The Overlook Press, 2009.

RILKE, RAINER MARIA. Trans. Edward Snow. The Poetry of Rilke. North Point Press, 2011.

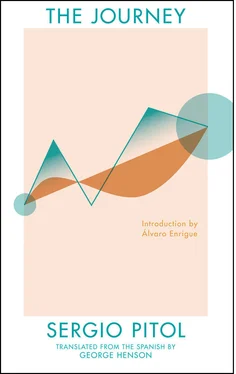

SERGIO PITOL DEMENEGHI is one of Mexico’s most acclaimed writers, born in the city of Puebla in 1933. He studied law and philosophy in Mexico City. He is renowned for his intellectual career in both the field of literary creation and translation, and is renowned for his work in the promotion of Mexican culture abroad, which he achieved during his long service as a cultural attaché in Mexican embassies and consulates across the globe. He has lived perpetually on the run: he was a student in Rome, a translator in Beijing and Barcelona, a university professor in Xalapa and Bristol, and a diplomat in Warsaw, Budapest, Paris, Moscow and Prague. In recognition of the importance of his entire canon of work, Pitol was awarded the two most important prizes in the Spanish language world: the Juan Rulfo Prize in 1999 (now known as the FIL Literary Award in Romance Languages), and in 2005 he won the Cervantes Prize, the most prestigious literary prize in the Spanish language world, often called the “Spanish language Nobel.” Deep Vellum will publish Pitol’s “Trilogy of Memory” in full in 2015–2016 ( The Art of Flight; The Journey; The Magician of Vienna , all translated by George Henson), marking the first appearance of any of Pitol’s books in English.

GEORGE HENSON’S literary translations include The Art of Flight by Cervantes Prize laureate Sergio Pitol and The Heart of the Artichoke by fellow Cervantes recipient Elena Poniatowska. His translations of essays, poetry, and short fiction, including works by Andrés Neuman, Leonardo Padura, Juan Villoro, Miguel Barnet, and Alberto Chimal have appeared in The Literary Review, BOMB, The Buenos Aires Review, Flash Fiction International , and World Literature Today , where he is a contributing editor. George holds a BA in Spanish from Oklahoma University, an MA, also in Spanish, from Middlebury College, and a PhD in literary and translation studies from the University of Texas at Dallas.

Читать дальше