It was a dictionary. All those years she had been writing a dictionary. A Bulgarian — Arabic dictionary, which she had left piled up in neat bundles secured with rubber bands.

25

SOON AFTER HIS MOTHER’S DEATH, Ulrich converted her bedroom into a chemistry laboratory.

He moved her bed out into the corridor, where it stood on its side for years before he finally chopped it up for firewood.

He set up a workbench and laid out all the equipment he had stolen from the factory. He installed an extractor fan that propelled effluent gases through a length of corrugated piping hanging out of the window. He brought barrels of petroleum and canisters of chlorine. He erected a small oven.

There were echoes of the garden laboratory of his childhood, for though he had seen many real laboratories since then, he still had in mind the same dramatic descriptions from the same old adventure novels.

Ulrich set out to discover plastic.

The 1970s were already well advanced. In the shops downstairs from Ulrich’s apartment, there were plastic cups and trays. There was polystyrene packaging and polythene bags. His own house was full of plastic pens and vinyl flooring, and even the clothes he wore were polyester. His sofa was stuffed with plastic foam. The casing of his television was plastic, and there was a plastic clock on the wall.

But Ulrich’s knowledge of polymers dated from his time in Berlin, half a century before, when all of these materials lurked in the void of the future. The intervening time had added little to his theoretical understanding, for he had become cut away from the world of research. He had only vague ideas as to how nylon might be made, or even vinyl. In his scientific world, the entire empire of plastics still had to be invented — and he set out as a late-coming pioneer.

He devoted several years to fundamental experiments, and taught himself many of the principles of polymer science. He developed a range of materials with different properties, and he began to test how they responded under various conditions. He learned how to adjust hardness, plasticity and heat resistance.

He drew his plastic curtains on the world outside. There was a plastic lamp on the bench, in whose bright circle he lived, day and night.

There were occasional accidents and his neighbours sometimes came to complain about the smells and the explosions. They were suspicious of his perpetual confinement.

There were days of euphoria, the ethylene gas coming off in a hot polymer slurry, and drying solid. He gazed at glistening blobs of virgin plastic, and he felt the satisfaction of having planted himself in something outside himself.

His inner thoughts from those days are mostly sealed off to him now. When he remembers what he did, he is reminded of a monkey he once saw in the Sofia zoo, beating its head rhythmically in its cage. Or the parrots he read about in a magazine, who pulled their feathers out when explorers caged them and took them away.

The police came to the apartment. It was after his remaining hair had turned grey, because they remarked on it. They complained of the smells and the dirt. They seemed alarmed at the conditions he was living in. They took him to a small room for questioning.

Ulrich had lost the habit of conversation, and was intimidated by the interrogation room. His eyes were wide with confusion, and the interrogator had to steady him.

‘There is nothing to worry about,’ he said. ‘We’re not trying to scare you. We just want to understand what you’re doing. Your neighbours are concerned.’

There was a lamp in Ulrich’s eyes, which released glowing spores in front of the interrogator’s face. They turned it off to calm him.

‘When did you last take a bath, comrade?’ the interrogator asked.

The question seemed easy, but Ulrich’s mind had become a vacuum. There were three men gathered around him who seemed to think there was a truth inside him that they would persuade him to part with. But inside him was nothing. He could not even remember when he last had a bath.

‘What is the purpose of the experiments you are conducting in your apartment?’

This, too, was impossible. Ulrich foundered on purpose . The interrogator tried to simplify his approach.

‘Are you making something?’

‘Yes,’ replied Ulrich.

‘Well, what are you making?’

‘Plastics. Various kinds of plastics.’

‘Plastic. Like this, you mean?’

He knocked his knuckle against the plastic clock that stood on the table between them. Ulrich picked up the clock and examined it.

‘No, not like this,’ he said at length. ‘This is made of polycarbonate. I don’t know how to make that.’

‘So what do you make?’ asked the interrogator patiently.

‘My experiments are still at an early stage, and I don’t know where they will lead. At present I am trying to develop some transparent materials using acetone and hydrogen cyanide. I may succeed, I may fail.’

‘Hydrogen cyanide. That sounds dangerous.’

‘I wear a gas mask,’ said Ulrich reassuringly. His nerves had calmed down.

The interrogator asked,

‘What do you intend to do with these transparent materials? Supposing you succeed?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Ulrich.

‘Let me ask you this. Are you running an illegal business? Are you trying to undermine our socialist economy?’

‘No,’ said Ulrich.

‘You don’t intend to sell what you make?’

‘No.’

‘How can you afford to buy your supplies?’

‘From my pension. I have no other expenses. And I have some savings.’

The interrogator was silent. Ulrich said,

‘If someone wanted me to make plastic things for them I might be able to do so. I think I could make buttons for a suit.’

‘But it is easy to get buttons for a suit!’

Ulrich picked up the clock and looked at it again. The interrogator continued,

‘Why do you do this, comrade? You are behaving like an eccentric and making people nervous. If it continues we will have to confiscate your equipment. And who would suffer from that? You are using dangerous chemicals in a residential building. There are several chemistry clubs you could belong to, where everything would be above board.’

‘No,’ said Ulrich. ‘I want to do it in the proper way.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘The proper way. The authentic way.’

Ulrich remembers that his door wore padlocks like so many earrings, and it was reinforced with steel. He plugged his keyhole and kept his curtains drawn.

He began to manufacture plastic objects. He made plastic dolls and animals. He sculpted a plastic comb, painstakingly, tooth by tooth. He did not have moulds, and everything he made looked like craftwork: irregular and roughly shaped.

He conducted some experiments with colouring, and set himself the task of producing a replica of his mother’s imitation tortoiseshell sunglasses, which had sat on a sideboard in the main room all this time.

He had to construct his own equipment: a reactor loop made of two new car exhausts he found, and a pump he had stolen from the factory. He used a chromium catalyst that he powdered himself. He needed high temperatures, and the apartment sweated. He used phthalic anhydride to make the frames more flexible, which he produced on his own, from naphthalene.

How many years of work did it take him to produce the material for the lenses? He remembers producing the first successful sheet, pressed between sheets of aluminium foil under a pile of heavy books. When he drew it out it was unintentionally embossed with the words Dictionary of the Bulgarian Language , and the device of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

He made moulds out of concrete, lined with aluminium foil. He used his own weight to hold the moulds closed while he injected the plastic with a hand pump, and he crouched there, on the mould, until it had cooled. He lifted off the top, pulled out the foil, and peeled it away carefully from the plastic. Glistening, and still warm.

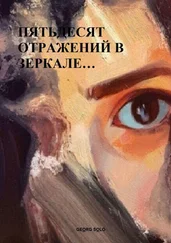

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу