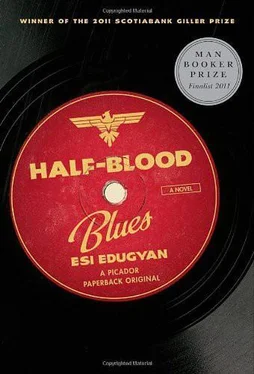

Well, hold on to your hats. So this Berlin scholar, he starts digging. And once in the mud he starts seeing similarities between the five Hot-Time discs and the warped, genius one. In some ways it sounds like the same band, just pared down, but. Well, there’s just something more torrid, more intelligent, stranger, hotter about that phantom disc. Not that the Hot-Time Swingers wasn’t good. Once upon a time we was the stuff . Played the greatest clubs of Europe, our five recordings as famous as anything. We had fans across the continent, played Austria and Switzerland and Sweden and Hungary and even Poland. Only reason we ain’t never gigged in France was cause Ernst, a proud son of a bitch, he held a war-based grudge. Lost it soon enough, when old Germany started falling apart. But before that our band was downright gold, all six of us: Hieronymus Falk on trumpet; Ernst ‘the Mouth’ von Haselberg on clarinet; Big Fritz Bayer on alto sax; Paul Butterstein on piano; and, finally, us, the rhythm boys — Chip Jones on drums and yours truly thumbing the upright. We was a kind of family, as messed-up and dysfunctional as any you could want.

So the scholar digs all this up. But then he gets stuck, unsure of himself. Right away he knows it’s old Hiero on lead trumpet. Well, congratulations, he wins a point. It takes him a couple weeks to decide it’s me on bass and Chip on drums. Ooh, you on a roll now, boy. But then he can’t fathom the second trumpet at all, assumes it’s got to be Ernst the Mouth. Seems the old owl read somewhere that despite Ernst’s preference for the licorice stick, he was also an able trumpeter. (False false false. Old Ernst played trumpet like Monet traded stocks.) And man, he can’t figure for the life of him why the other Hot-Timers ain’t on the recording.

Now, he wasn’t all wrong. He does discover Paul was arrested in ’39 and died in Sachsenhausen. He figures out Chip and me returned to America on the New-York bound SS St. John . That the kid was arrested in Paris and taken to Mauthausen via Saint-Denis. But where’s Big Fritz? And where did Ernst disappear to after the recording? All mysteries.

The musicologist’s essays caught the eye of John Hammond Jr, that jazz Columbus who discovered Billie and Ella. Hammond was then a talent scout for Columbia, signing cats like Aretha, Bob and Leonard. He tracked down the disc in Berlin. And to hear Hammond tell it, our recording damn near made an amnesiac of him. We blown every last thought out of his mind. When he finally come to (don’t you love how these exec types talk?), he known he needed to do three things. One: convince Columbia to remaster and release the recording with huge distribution. Two: track down those of us ain’t dead yet. Three: tour us Hot-Time Swingers to fame, fortune and all that damned et cetera.

It was Louis helped him find me and Chip. Louis Armstrong. See, Armstrong known a thing or two, and despite hating Hammond he penned the man a letter setting things straight. That was most definitely not Ernst von Haselberg on second trumpet, he wrote, what a fool idea. If he had to guess, it was probably Kentucky’s own Bill Coleman. He explained the recording was based on a popular German song whose name escaped him. He also told him that me and Chip was probably living back in Baltimore, check there. He ain’t said nothing else, gave no details about how he might know any of this. Sure Hammond wrote him back. But not two days after posting the letter it was announced in the news that old Satchmo had died. Hammond found me and Chip in the phonebook .

Chip wasn’t shy. He said he didn’t know how Armstrong known all that. And he got me to agree to Hammond’s record deal — if it proved kosher with Coleman, that is — though I told him no way in hell would the Hot-Time Swingers ever go to tour. We’d known for years that Ernst, Big Fritz and Paul was all dead. Word gets back. And Hiero, well, there just wasn’t no Half Blood Blues without the kid. Cause it was his piece, see — he’d been the frontman, had written the damned thing in his own blood and spit. He had that massive sound, wild and unexpected, like a thicket of flowers in a bone-dry field. Ain’t no replacing that. And anyhow, Chip and me had no taste for resurrecting all that. Not after what had happened.

Of course, the recording’s cult status had to do with the illusion of it all. I mean, not just of the kid but of all of us, all the Hot-Time Swingers. Think about it. A bunch of German and American kids meeting up in Berlin and Paris between the wars to make all this wild joyful music before the Nazis kick it to pieces? And the legend survives when a lone tin box is dug out of a damn wall in a flat once belonged to a Nazi? Man. If that ain’t a ghost story, I never heard one.

One question kept flaring up, though: who was this Hieronymus Falk? Some of the wildest stories you ever heard come out, a couple of them even true. Folks reckoned he could play any song after hearing it just once (true); they believed he was Sidney Bechet’s long-lost brother (ain’t we all?); they murmured that like the bluesman Robert Johnson, Falk would only play facing a corner, his back to everyone (handsome devil like Falk? think again) — and speaking of the devil (and Johnson), they reckoned he’d made a pact with hell itself, traded his soul for those damned clever lips.

I don’t know, maybe that last one is even true.

Then in the fall of ’81 a few more details come out. In an interview Hammond gave, he claimed the kid died in ’48, after leaving Mauthausen. Died of some chest ailment that August, of a pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism? Somehow that ain’t struck folks as right. ‘What really happened to Hieronymus Falk’ become something of a journalist sport. All sorts of nonsense started up. One article said Falk got pleurisy. Another said pleurisy of the suicide variety, implying he brought it on himself, one too many rainy walks in that frail body. Still another said forget the lungs — it been his heart that give out, cardiac arrest due to starvation. More romantic that way, I guess. No one seemed to get it right. All of this was like an old knife turning in me and Chip’s guts. Leave the poor kid dead, we felt. Let him lie.

Through all of it, Hammond stuck to his guns.

‘It’s like I said, Sid, pulmonary embolism,’ he told me later. ‘I’ve never been more astonished than when everyone refused to believe it. A man like Falk, though, I guess he’s got to have a glamorous death. With the right kind of death, a man can live forever.’

Hell , I thought when I heard that. A man like Falk ? Hiero was just a kid . Ain’t nobody should have to grow up like that.

……….

I stood a long time behind my door, listening for Chip’s shuffled footfalls on the stairs. Then I locked the two deadbolts, rattled the chain into place.

Chip Jones , I thought grimly, as I went back down the hall. Chip goddamn Jones. The man don’t understand limits .

Not that I believed him. Even for a second. I returned to my quiet living room, turned off the lights, stood at the window with one slat of the blinds held down, staring out into the street. After a minute Chip appeared, a small silhouette in the gathering darkness. He crossed the street, walking slowly, then turned and glanced up at my apartment. I released the blinds with a crackle and stepped back into the shadows.

After a time I sat, looked at my hands. The room darkish now, the late afternoon haze laying shadows against all the furniture. Everything looked heavier. I could smell Chip’s cigarillo like the devil’s presence.

Then I said to myself, be fair, just picture it for a minute. What if this wasn’t some prank of Chip’s, what if these letters did exist, what if somehow, like the proverbial voice from beyond the grave, the kid was reaching out to us? What would you do, Sid, if all that was possible? After what you done, wouldn’t you owe it to him to go? I sat there until the room went full dark, staring through my warped living room blinds into the street.

Читать дальше