‘Hieronymus hasn’t touched his,’ she said suspiciously.

‘She says you drink like a girl,’ I said.

The kid ain’t reacted, just looked at her.

‘Go on,’ Ernst said again.

She lifted her thimble, give a sly little nod at the kid, punched it back.

We all watched her face.

She opened her eyes. ‘Jesus,’ she croaked. Her lips twist up, and she give a soft little shudder. We all started laughing. ‘That’s even worse than it looks. No wonder Hitler’s so angry, if he’s drinking this .’

There was water coming from her eyes.

It was damn wretched, that czech. I bet it ain’t even legal in half the states back home. The kid, he start laughing that high, broken, hiccuping laugh of his. Then he give her a startled look from under his hat brim.

But that jane just leaned forward, the low lights catching the ghostly rye of her skin, and all at once I seen it clearly. This girl was high yella, like me. A Mischling , a half-blood. She got the kind of mixed-race face only a keen eye can see.

‘Boys,’ she said, crossing one long leg over the other. I watched that blue hemline inch up, felt myself flush. ‘Boys, I’d like to invite you to Paris. To cut a record. We’re looking for exactly what you’ve got.’

Ernst said in German, ‘She wants us to go to Paris. To cut the wax.’

‘Paris,’ Paul repeated, frowning.

I was still staring at her slash of pale thigh when, glancing at her face, I seen she was watching me. I blushed. ‘You in the business ?’ I said. But it come out sounding sort of lewd.

There was a flash of impatience in her eyes. ‘I’m Delilah Brown .’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Of course.’

‘The singer ,’ she said after a moment. ‘ Black-eyed Blues? Dark Train Song? ’

I was nodding hard. ‘Sure. Of course. Delilah Brown .’

But I glanced over at Ernst, like to see if she was joking. Ain’t no singer I ever heard of.

‘She represents Louis Armstrong,’ said Ernst.

Hell. Now that we understood. Our whole table fell silent.

‘What she want?’ the kid said at last. His voice was real soft. ‘She a agent?’

‘You his agent?’ I said to her.

‘No.’

Paul brushed a golden lock back from his forehead, fixed his clear blue eyes on Ernst. ‘What are we talking about? She means Armstrong the horn-blower? For real?’

I shook my head. ‘No. She mean Armstrong the court jester .’

‘That was Archy Armstrong,’ Ernst said distractedly. ‘And yes. It seems she’s for real.’

I looked at him. ‘There a jester named Armstrong? Really?’

He nodded. ‘King James the First.’

‘Hell.’

That jane just watched us, not understanding a word. I guess she must have thought we was discussing her proposal, by the severe set of her jaw. ‘Well? What is it?’

At last Ernst give her a long, slow look. ‘You’re asking us to leave our lives, Miss Brown. It’s a difficult choice. If we go to Paris, we won’t be coming back.’

Her face tightened. ‘With all due respect, Mr von Haselberg. If you don’t go now, you won’t have lives to leave. You’re drowning here, we both can see it.’ She give a faint smile, like to soften her words.

Ernst brushed a fleck from his trousers. ‘We’re surviving.’

‘But not living . You know the difference. You don’t need to decide now, of course. But I’m offering you a chance to live again, to play your music. To walk the streets of a city not afraid of being arrested. Or worse, for god’s sake. Berlin is like a locked room to you boys. I’m offering you a way out .’

I barely caught all that. I was still looking at her thigh.

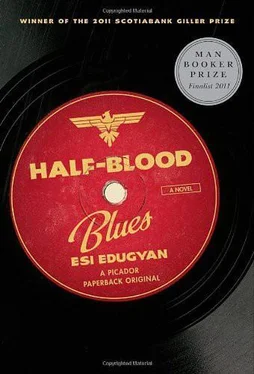

Jazz. Here in Germany it become something worse than a virus. We was all of us damn fleas, us Negroes and Jews and low-life hoodlums, set on playing that vulgar racket, seducing sweet blond kids into corruption and sex. It wasn’t a music, it wasn’t a fad. It was a plague sent out by the dread black hordes, engineered by the Jews. Us Negroes, see, we was only half to blame — we just can’t help it. Savages just got a natural feel for filthy rhythms, no self-control to speak of. But the Jews, brother, now they cooked up this jungle music on purpose . All part of their master plan to weaken Aryan youth, corrupt its janes, dilute its bloodlines.

We lived with that for ten damn years. Through the establishment of old Joe Goebbel’s Reichsmusikkamer , his insistence that all musicians ‘register’. Through that ugly Düsseldorf exhibit last spring. Hell, let me help you picture it. Take ‘37’s Degenerate Art soirée in Munich, replace the paintings with posters of jungle minstrels squawking on their saxes, and flood the rooms with beautiful music, and you got the idea. We was officially degenerate.

And like a shadow running beneath all that, there was gates scrubbing cobblestones with rags, gates getting truncheoned just for sitting in a damn café, gates reduced to eating from backstreet garbage bins. And the poor damn Jews, clubbed to a pulp in the streets, their shopfronts smashed up, their axes ripped from their hands. Hell. When that old ivory-tickler Volker Schramm denounced his manager Martin Miller as a false Aryan, we known Berlin wasn’t Berlin no more. It been a damn savage decade.

So, Paris sounded pretty tempting.

Problem was the papers. Wasn’t no way folks like us was getting the right papers to go to Paris. It ain’t been possible for years now.

Don’t get me wrong — I loved Berlin. I ain’t saying otherwise. And for awhile the Housepainter didn’t even seem as bad as old Jim Crow. Least here in Europe a jack felt a little loved for his art — even if it was a secret love, a quick grope in the shadows when no one was looking. I ain’t took it personal. Truth was, I didn’t look all that black, and to those who suspected the truth, well, congratulations. Pour youself a drink.

Cause blacks just wasn’t no kind of priority back in those years. I guess there just wasn’t enough of us.

The Jewish baths was half-falling down, half-broken, most of the pools already closed to the public. But it was the only baths some of us still legally allowed to use, and sometimes a jack just ache for the fragrance of boiled stones, for the hot and freezing waters. The clear green pools sunken like craters in the earth. We’d just put our heads back and glide, naked as the day we was born.

Chip and Fritz was waiting for us in the changing room. Chip had his shoes off, stood wriggling his damn toes on the stone floor.

‘You ain’t gone in yet?’ I called. ‘We reckoned we smelled you from the street.’

‘You smellin Fritz, maybe,’ said Chip. He lift up his chin, waft the air from under it. ‘Unless you smellin Dr McMorran’s Special No. 9.’

Paul sniffed the air. ‘What is that? A cough syrup?’

‘It medicine alright,’ I said. ‘For head cases.’

‘It’s the scent drive the ladies wild ,’ said Chip.

‘It the scent drive the ladies out the room ,’ I whispered to the kid.

Hiero grinned, thrilled to be in on the teasing.

Big Fritz sat slumped on the hard wooden bench, huge, flushed and tired-looking. He was a massive Bavarian, with thick fingers, straw-like hair, and a strong, hawkish nose. He was broad as a damn trolley to boot. He lumbered upright, breathing heavily in that hot change room.

‘You alright, Fritz?’ said Ernst, coming over. He set his hat down gentle on the bench, begun untying his laces.

Fritz waved one hairy hand. ‘I’m fine. Just worn out.’ His low voice boomed throughout the room — you almost felt the rafters shuddering. He blinked his slow lids, the sweat shining on his hairline.

Читать дальше