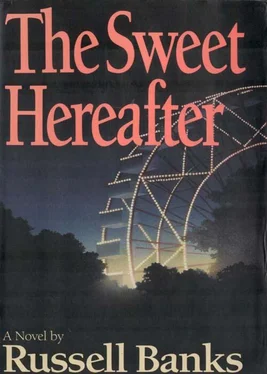

Russell Banks - The Sweet Hereafter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Sweet Hereafter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, Издательство: Little Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet Hereafter

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet Hereafter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet Hereafter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet Hereafter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet Hereafter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“No way,” I said. “I’m never going back to that school,” I said, and I noticed he didn’t argue very hard. Mom didn’t, either, but she never argues hard when an official man is around. She just takes her cues from him and agrees. Later on, Daddy tells her what she should have said.

Anyhow, I don’t think Mr. Dillinger wanted me wheeling around the school reminding everyone of the accident and the kids who had died in it. They’d hired some woman from Plattsburgh, I heard, and arranged all these special group therapy meetings and assemblies for the kids after the accident, and things had more or less returned to normal now. Besides, Mr. Dillinger knew I could do all the work at home and still be ahead of most of the kids in my class, except for the real brainy ones. And next year my class would all be going on to high school in Lake Placid, and then I’d be somebody else’s problem.

I didn’t want to stay home alone with Mom all day, that’s for sure, but I really did not need to see any of the kids from school. I didn’t want to watch them strolling around in the hallways and the cafeteria, sneaking into the lav between classes to put on lipstick and share a cigarette, going off to cheerleading practice and hanging out after school in the parking lot together. I didn’t want them to stop what they were doing or saying when I rolled up in my wheelchair, “Hi, guys, what’s up?” I knew what I’d look like to them, how they’d all go silent for a minute when the dweeb arrived and then change the subject not to embarrass her or make her feel bad because they were talking about something she couldn’t do, like dancing or sports or just hanging out. Poor Nichole, the cripple. That’s the best I’d get from them — pity. And no matter how many of those group therapy sessions they’d been to, everyone would see me and instantly think of the kids who weren’t there anymore, the kids who had not been lucky like me, and maybe they would hate me for it. And I wouldn’t blame them.

At the hospital, lots of kids from school, even the little kids from the Sunday school class I taught, had come to visit me, like official delegations at first, in groups of three and four at a time, but it was always self-conscious and embarrassing, especially with the kids my age, my friends, so called, and I knew they could hardly wait to leave, and I was glad myself when they did. Then only my best friend, Jody Plante, and one or two others, when they could get someone to drive them over, came to visit, and that was okay. But by the time I left the hospital to come home, I had pretty much run out of things to talk about with them. We were living in different worlds now, and they couldn’t know about mine, and I didn’t want to know about theirs anymore.

For a while after I got home, Jody called me on the phone and even came over once or twice, and she yacked brightly about school and cheerleading gossip and boys, the usual stuff. But she was forcing it, I knew, and I never seemed to have the desire to call her, and of course I couldn’t visit, so pretty soon she didn’t call me anymore and never came to visit, either.

I stayed in my new room, with the door closed and locked, except when I came out to eat or use the bathroom. For supper, I had to sit at the table with the rest of the family, but breakfast and lunch I usually ate alone. One Saturday morning Mom and Daddy moved everything in the cupboards — dishes, glasses, food, everything — down to the lower cabinets, so I could reach them from my wheelchair. It was Daddy’s idea. I think Mom would have preferred to have me go on asking her for help every time I wanted a sandwich or a bowl of cereal. But since Jennie was in school now, Mom was gone a lot of the time herself, working part time over to the Grand Union in Marlowe, so she had to go along with my taking care of myself in the kitchen.

During the days, I pretty much had the whole house to myself, but I still stayed in my room. One night Daddy brought home a portable black-and-white TV for me that he had bought used in Ausable Forks, and he tied it into the regular cable, so I was able to watch TV then without leaving my room. Soaps and game shows, mostly, which were fine by me. And music videos. And Oprah and Donahue and Geraldo. After a month of that stuff you feel like it’s all one show, ads and everything, and you’ve been watching it for years. But I had Mr. Stephens’s computer to play with, and plenty of schoolwork to do, and books that Mrs. Twichell, the school librarian, brought over for me, mostly sappy young-adult novels about race relations and divorce, which I don’t like but will read anyhow because the writers seem so intent on having you read them that you feel it’s impolite not to.

Things with Daddy were different now too. I had become a wheelchair girl, and I think that scared him, like it does most people. You see them on the street staring at you and then looking away, as if you were a freak. To Daddy, it was like I was made of spun glass and he was afraid he would break me if he touched me. Probably I wasn’t pretty to him anymore, either, and he couldn’t pretend that I was like some beautiful movie star, the way he used to. Miss America, he always called me. “How’s my Miss America today?” But not anymore. Which was fine by me. If he did touch me, by accident or because he couldn’t avoid it, like the time he had to carry me up the stairs at the courthouse in Marlowe when I had to make my deposition for Mr. Stephens and the other lawyers, he backed away from me right away and wouldn’t look at me.

I looked at him, though. I looked right into him. I had changed since the accident, and not just in my body, and he knew it. His secret was mine now; I owned it. It used to be like I shared it with him, but no more. Before, everything had been fluid and changing and confused, with me not knowing for sure what had happened or who was to blame. But now I saw him as a thief, just a sneaky little thief in the night who had robbed his own daughter of what was supposed to be permanently hers — like he had robbed me of my soul or something, whatever it was that Jennie still had and I didn’t. And then the accident robbed me of my body.

So I didn’t own much anymore. My new room, maybe, and Mr. Stephens’s computer, which weren’t really mine and weren’t worth much anyhow. No, the only truly valuable thing that I owned now happened to be Daddy’s worst secret, and I meant to hold on to it. It was like I carried it in a locked box on my lap, with the key held tightly in my hand, and it made him afraid of me. Every time he saw me looking at him hard, he trembled.

I remember the first time Mr. Stephens came over to the house, how strained and nervous Daddy was when he wheeled me out into the living room and introduced me. It was like Mr. Stephens was a police officer or something, probably because he’s such a big shot lawyer and all, and Daddy was afraid I’d say something to make him suspicious.

Of course, he was also afraid that I would refuse to go along with their lawsuit. I still hadn’t agreed to do it, not in so many words, but in my mind I had decided to go ahead and say what they wanted me to say, which they insisted was only to answer Mr. Stephens’s and the other lawyers’ questions truthfully. That couldn’t hurt anything, I figured, because the truth was, I didn’t really remember anything about the actual accident, so nothing I said could be used to blame anybody for it. It was an accident, that’s all. Accidents happen.

Mr. Stephens was this tall skinny guy with a big puffy head of gray hair that made him look like a dandelion gone to seed and a gust of wind would blow all his hair away and leave him bald. I liked him, though. He had a small pointy face and red lips and a nice smile, and he looked right into my eyes when he talked to me, which is something that most people can’t do with me. Also, he reached down and shook my hand when Daddy introduced us, which I liked. Adults almost never do that, especially with girls. And with wheelchair girls, I’ve noticed, they actually take a step backward and put their hands on their hips or in their pockets, like you’ve got something they don’t want to catch. Mr. Stephens, though, after he shook my hand and Daddy went to stand edgily by the porch door, pulled a kitchen chair up next to my wheelchair and sat right down and got his head the same level as mine, and I felt like he could see that I was really a normal person.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet Hereafter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet Hereafter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet Hereafter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.