The next afternoon, a Sunday, Doctor Wickshaw arrived bearing a portable television set for Carol and immense good cheer. It was a bright, warm day, and the son and daughter-in-law were home, downstairs in the living room reading the Sunday papers and watching a football game on the large color TV. They had come upstairs that morning around nine, had taken a minute to study the old man in Carol’s silent presence, and had asked her if she wanted to go to church. She said no, thanks, and with clear relief, they returned to their quarters.

Doctor Wickshaw, too, made a brief show of examining the patient, albeit with more precision than the old man’s survivors had. He listened to his heart, took his blood pressure, studied Carol’s notes on the man’s temperature, medication, bodily functions, and so on. Then, clamping shut his black leather bag, he placed it at the foot of the bed, sighed and observed that it wouldn’t hurt the old man if she took off for a few hours. “They’ll be here all afternoon,” he said, indicating with a nod toward the door the couple downstairs. “You must want a break.” He was wearing a brown corduroy shooting jacket with tan leather patches at the elbows and over his right shoulder, green twill trousers and a tattersall shirt. His short, white hair and beard bristled like antennae, and he rubbed his hands together happily.

Carol thanked him for the use of the television set and said no, she’d be just as happy to stay here at the house. She might take a walk later. “You’ve already been plenty kind to me.”

“No, no, you’re coming with me,” he said. “You need a break at least once a week or you’ll get wacky out here with no one but ol’ Harold for company.” He grinned, showing her his excellent teeth. “C’mon, now, go in there and change into some civilian clothes,” he said, pointing with his bearded chin toward her white uniform, “and I’ll wait for you outside. It’s a gorgeous day!” he exclaimed, darting a look out the window.

“All right.”

“That’s a good girl.” He left, and she turned, glancing as she departed from the room at the body of the old man in the bed. He was awake, blinking his watery eyes and looking at the space in the room she had just filled. He had a puzzled expression on his gray face, as if he were wondering where she had gone.

She turned away from him, and when she went into her own bedroom, she closed the door.

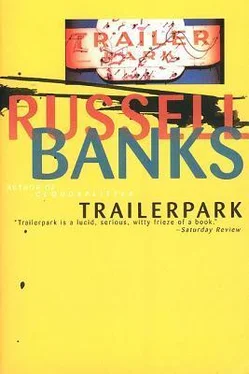

Doctor Wickshaw, or “Sam,” as he insisted on being called, talked steadily throughout the tour. He drove his huge, maroon Buick rapidly, nervously, waving his arms and pointing right and left at hills, trees and water as they passed Skitter Lake glistening in the sunlight and choppy in the breeze. They stopped for a minute at the Granite State Trailerpark so he could show her the remains of the old Indian fishing weirs, cruised through the center of town, with Sam enumerating, as they passed them, the several churches, the fire station, the police station, the town hall, the Hawthorne House, where, he told her, they often had first-class country and western bands playing, then stopped for a few moments at the park to watch a gang of teen-agers drink beer at a picnic table. On High Street, when they passed a large, white, Victorian house with a sign outside that said, SAMUEL F. WICKSHAW, M.D., the doctor slowed his car almost to a stop. Half the yard had been paved for cars, and the barn attached to the house in back had been converted into an office.

“I could run a clinic from that building,” Sam said in a tone that was almost wistful.

“Why don’t you?” Carol asked. It wasn’t difficult to admire the meticulous, white buildings, the white picket fence that ran along the front, the carefully tended flower gardens covered with wood chips and awaiting the arrival of winter. Evergreen shrubs along the front of the house had been covered with burlap, and she could see on the side porch several neatly stacked cords of fireplace wood.

“Can’t get the help.”

“Really?”

“Would you believe that the woman who’s been my nurse and receptionist for over a year now was trained as a dietician? Bless her, but she’s fifty-nine and can’t do much more than open a can of Band-Aids for me.” He sighed and drove thoughtfully on.

Back at the house, he pulled into the circular drive and parked. Carol reached for the door, but Sam turned toward her, and slinging his right arm over the seat back, he grabbed on to her shoulder with his hand. “Wait,” he said, suddenly serious.

His hand against her dark blue wool sweater was pink and blotched with liver spots, and his nails were white and carefully trimmed. She looked at the hand with curiosity, as if a leaf had unexpectedly fallen from a tree and landed there.

“I like you, Carol.” He cleared his throat. “You’re a fine nurse, and I like you as a person.”

“Thank you, Doctor.”

“Sam.”

“Yes. Sam.” With her right hand, she pulled the latch, and the heavy door of the Buick swung open.

“Well,” he said, smiling broadly again and releasing her shoulder. “I just wanted you to know you’re among friends up here in God’s country.”

“Yes. That’s … that’s nice of you.” She stepped free of the car and closed the door solidly, walked around in front of the car and gave a little wave good-bye.

He rolled down his window and called to her. “Carol. We’ll talk some more. Eh?”

“All right,” she said, her voice rising. “And thank you.”

He waved, closed his window, and drove swiftly off. For a moment she stood by the front door of the house watching him. A crow called harshly from the open field behind the house, and she could hear the afternoon breeze push through a stand of tall pines by the road. Then she opened the door and went quickly upstairs to her room.

Hurriedly, she shed her wool skirt, sweater and blouse and went to the closet and brought out her uniform, when, as if remembering something, she turned, padded barefoot across to the door that led to the bathroom and the room beyond, and opened it. She stood there in the doorway, holding her white uniform over one forearm, and looked at the man in the bed. His chest rose and fell slowly. His eyes were closed, and his mouth lay dry and open, his face slack as if being drawn by a great weight into the pillow. His gray hands twitched erratically above the sheet, his palms facing the ceiling, and he seemed to be pushing at a great, smothering blanket in his dreams.

November arrived, and with it the deer-hunting season, and all day long Carol heard gunfire coming from the woods behind the house. She could look out the window of her room and see miles of forest, leafless oak and maple trees, and along the ridges in the distance, blue spruce and balsam. Now and then she saw a red-suited figure with a rifle emerge from the woods and cross the brown field toward her and disappear at the side of the house. It had once been a farmhouse, with barns and outbuildings, but no longer. Modern plumbing and heating systems, picture windows, a pine-paneled recreation room and a large, renovated kitchen with a breakfast nook and gleaming new appliances had eliminated from the interior of the house all traces of the families that had owned the house before Harold Dame. It sat on a rise of land two miles west of town. Looking east, you could see the spires of the churches and here and there among the trees shining bits of the mill pond and, a ways farther, the lake. Spotted in the distance on the hills and ridges were houses and barns, old farms, most of them no longer farms but the renovated residences of people who made their livings in town from selling insurance, real estate, automobiles, snowmobiles and housetrailers to their neighbors and each other.

Читать дальше